We have written for years about the impact of the decline of the icebreaker force in the USCG on US Arctic policy.

We referred to the US as the “reluctant Arctic power.”

In our interview with the USCG Commandant Admiral Paul Zukunft we focused on the need to shift policy and to add the kinds of assets the USCG needs to able to fulfill a core mission.

Question: With regard to the Arctic, there is an obvious need to ramp up US presence and the resources to provide for presence.

How do you view the way ahead?

Admiral Zukunft: “We clearly need a new icebreaker.

“We’ve written the operational requirement documents that make the icebreaker a floating command and control platform.

“We can put a skiff on it. It’s also an instrument to enforce sovereignty.

“Rather then ice hardened, you have actually an ice breaking capability up there as well.

“It is extremely hard to predict what that area’s going to look like in 20, 30 years but without a new icebreaker we will be observers more than participants in shaping Arctic safety and security.

“An independent High Latitude analysis confirmed that we need three and three – three heavy and three medium icebreakers.

“We have helped stand up an Arctic Coast Guard Forum based on the Pacific Coast Guard Forum model.

“This allows the key national stakeholders in Arctic safety and security to work together where possible to enhance safety and security in this dynamic region.

“We are looking to do a mass rescue exercise in 2017 around Iceland that will bring in Denmark and other NATO partners for a collective security effort.

“And to be clear, the USCG is the key sea service for the Arctic, the USN has in effect devolved Arctic security responsibilities to the USCG.”

Later this week, the USCG is to release its request for proposal for a new heavy icebreaker.

According to a story by Ben Werner published on USNI News on March 1, 2018:

Speaking Thursday during his final State of the Coast Guard address, Zukunft said the icebreaker program is part of a funding pivot point, with a $11.6-billion funding request for Fiscal Year 2019 that will shape the Coast Guard for the next 40 years.

“We are building out the Coast Guard of tomorrow, and to do that we will need 5 percent annualized growth in operations and maintenance account and a $2-billion floor for acquisitions to continue to do so,” Zukunft said.

“It is a small ask, for the smallest armed service whose full appropriation is less than one line item on the appropriations of the other four armed services.”

While Zukunft pointed to several achievements during the past year, securing funding for a new heavy icebreaker represents a fundamental shift in how the Coast Guard advances U.S. policy in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.

“We are trusted in the Arctic to preserve our sovereignty over precious oil and minerals, to ensure access to opening shipping routes, and let’s not forget, to keep our border secure in a region with an emerging U.S. coastline and mounting Russian footprint,” Zukunft said.

Currently, the Coast Guard only has one heavy icebreaker, USCGC Polar Star (WAGB-10), which was commissioned in 1976 – shortly before Zukunft started his 41-year Coast Guard career after graduating from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in 1977.

In the following article which we published in 2011, we discussed with Rear Admiral (Retired) Jeffrey M. Garrett, a man with significant Arctic experience, the importance of the icebreaker to US national security policy:

12/19/2011 Shortly before he was to testify before Congress with regard to the Arctic, Rear Admiral Jeffrey M. Garrett, U.S. Coast Guard (Retired) sat down with Second Line of Defense to provide our readers with an update.

SLD: The icebreaker is an extremely important asset for presence in the Arctic and as you described operates as kind of a mother ship in the Arctic. What’s the current situation with the US icebreaker fleet?

Garret: The current national multi-mission polar Icebreaker fleet is three right now. Unfortunately, neither of the 35-year-old polar class vessels is operational; one is laid up, the other one is undergoing a multiyear refurbishment project. The only operational Icebreaker is actually a less powerful, more modern ship, the Healy, which is actually deployed in the Arctic right now.

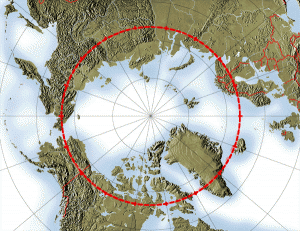

The Icebreaker fleet represents the main surface presence that the U.S. can exert in what is essentially a maritime domain in the Arctic Ocean. An area that is becoming much more accessible to a whole range of human activities. And it’s clearly brought Arctic Alaska, the U.S. piece of the Arctic into a new concern for the Coast Guard, particularly in terms of exercising its statutory responsibilities there. It is obviously important as well for protecting broader national interests, such as presence, sovereignty, and even support of defense operations.

The Icebreaker is really the platform that can give you year-round access to that for both the broader national interest, as well as being able to conduct Coast Guard operations.

SLD: A lot of folks Inside the Beltway say that these Arctic missions are very futuristic, and some would argue that we’re in a financial crisis and we can’t afford an Arctic presence. How does our inability to play going to affect our interest in the very near-term?

Garret: To get to the first part of your question, the Icebreakers are clearly very expensive ships compared to others. But really, the perspective should be what is the cost of not having an Icebreaker? If you have a major contingency in the Arctic, whether it’s security related, oil spill related, or something like that, even search-and-rescue, or tourism ships getting in trouble, you have no way of responding. And the cost of not being able to respond to those things may be very high.

The Icebreaker is an insurance policy against future contingencies in a rapidly transforming Arctic.

SLD: We were talking a little bit earlier about, in effect, about a fleet concept, which would include the Arctic. The way we’ve looked at it is a Pacific strategy from the Arctic to Australia. And you were focusing very much on building some commonality of the National Security Cutter fleet that would be in the Pacific and with the Coast Guard with a evolving icebreaker fleet. How would that work? What’s your vision of integrating NSCs and future Icebreakers?

Garret: What’s changed for the Coast Guard is that the Icebreaker fleet no longer is just performing science and missions for other agencies. It’s now becoming a core Coast Guard asset in terms of being able to execute Coast Guard responsibilities in the Arctic, and in the Antarctic, for that matter.

A future Icebreaker is essentially a national security cutter set of capabilities with the additional ability to operate in ice covered waters, and for extended periods of time. So really, it’s not an odd animal that’s kind of an add-on to the Coast Guard fleet; it’s really central to the whole core concept of being able to do Coast Guard missions at sea a long way from homeport.

And I think the ability for these kinds of ships to exert a surface presence, in a whole range of things from the most simple peacetime task, such as search-and-rescue, to all the way up to security and defense related issues is a highly effective tool that the United States needs.

SLD: And I guess the final point is when you say surface presence, of course, there are air assets coming off of these Icebreakers as well. And as we go over time, we’re going to have to build out the capabilities of what could be on that ship.

Garret: Absolutely. I think having rotary wing assets on the ship is a key part of this. The icebreakers have a lot of other capabilities, which include the ability to have sophisticated command-and-control communication systems, to carry cargo, to have container spots on deck so you can modularize a lot of your mission packages when you want to specialize it for certain missions. There are other aspects as well such as extra berthing, an ability to carry small boats, etc. It’s really a floating base in the Arctic, in a place where there really is no infrastructure.

For earlier SLD pieces discussing the Arctic with Rear Admiral Garrett, please see

https://www.sldinfo.com/ending-reluctance/

https://www.sldinfo.com/operating-in-the-arctic-resourcing-for-the-21st-century/