As foot soldiers are in increased demand in the harsh terrain of Afghanistan while IEDs have created new types of vulnerabilities, individual protective gear for the infantryman keeps evolving and improving to address new kinds of challenges. SLD’s Murielle Delaporte sat down with USMC Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur J. Pasagian, Program manager, Infantry Combat Equipment (ICE), to discuss such a process of adaptation with a special focus on one of the most crucial protective item today’s Marines rely on, i.e. body armor.

Marines with 2nd Platoon, Company W, Task Force 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, Regimental Combat Team 1,

search for weapons caches in a joint effort with Iraqi police, Jan. 10. The IP coordinated cache sweep in La Hib,

northeastern Karmah, demonstrated the proficiency of Karmah’s police and resulted in hundreds of pounds of explosives,

blasting caps, pressure switches, and detonating devices being uncovered during the 13-hour search.

***

AN OVERVIEW

Today’s battlefield seems to require more of the same all across the spectrum of military equipment, i.e. more protection, more power and lethality, more mobility and agility, more stealth/silent/low heat signature, more maintainability and sustainability, more situational awareness ability… For the soldier on foot – whether Marine, Special Forces or Army -, this tends to translate into heavier and heavier loads of specialized equipment and protective device. A typical Marine combat load will include in addition to protective gear and the bare necessities (i.e. food and water) weapons, magazines, communications gear and the energy to sustain the latter. In Afghanistan, a three-day mission can require up to 150 pounds of individual loads. On the other hand, focused research and development towards lighter weight and miniaturization has lead to major improvements in this area, while the “soldier modernization” market, which emerged in the 1990’s and “generated a total $440 million in sales worldwide during 2008”, is considered very promising in the future. Some estimates anticipate a total of $6 billion to be spent between 2009 and 2015 on body armor alone for US Army soldiers and Marines.

New Afghan Specs: Looking for Long-Haul Sustainment

Notwithstanding the tough conditions of patrolling in thin aired high-altitude mountains (i.e. more than 10,000 feet), the accumulation and length of multiple tours of duty either in Iraq or in Afghanistan would be enough to explain the publicized increase in what is referred to as “non-deployables”, i.e. military personnel unable to be redeployed because of injuries: the total number of non-deployables has been estimated at about 20,000 with an increase of 2 to 3,000 between 2006 and 2009 and an annual injury rate of 2.2 injuries per active-duty soldier according to an article published last year in the Washington Post. Indeed, for Lieutenant-Colonel Pasagian, “heavy loads are nothing new in the USMC world and training is tailored to match the weight and fitness requirements“. Intensive strength training accross the board can help reduce injuries by up to 45%, while soldiers curriculum also tends to include basic physical therapy notions to prevent the latter (most Army active-duty combat brigades nowadays even count a physical therapist in their ranks when deployed).

Basic USMC training for units deployed to Afghanistan also tends to include the lost skills of using local animals to ensure “long-haul sustainment”, such as packing a mule : revived in the eighties when the United States were helping Afghans fighting the Soviets, the California-based Marine Corps’s Mountain Warfare Training Center is keeping the lost art alive among the next generation of warfighters.

But the main focus to enhance the latter’s mobility on the ground against an ever more agile enemy while maintaining the same level of protection and capabilities which proved successful in Iraq is to bet on technological breakthroughs and work on a joint basis whenever possible. The axis of research aiming at reducing the soldier’s individual weight and logistic footprint are numerous and include:

- taking a few pounds off here and there on different items the latter must – or would like to – carry, or increasing the protection while minimizing the subsequent weight increase: it is the case for instance for the joint US Army/USMC Next Generation Combat Helmet (ECH) program, which aims at augmenting ballistic protection against fragmentation by 35% while maintaining the same weight; it is also the case of the US Army Land Warrior system, aimed at providing the soldier with situational awareness, maps, imagery, voice and text messaging capabilities, via a helmet-mounted display, which started at 17 pounds, was almost abandoned for that reason and is now back on track at 7.2 pounds a piece; it is also the case of anything which needs to be carried such as rucksacks (e.g. SOCOM Body Armor Load Carriage System or the “medium ruck” currently being designed with Afghan requirements – i.e. days of walk – in mind) or guns;

- improving the design and self-sustainability of equipment: making equipment work with simple AA batteries rather than uniquely-built ones each soldier must carry with him – like the new generation of thermal sights for assault rifles and machine-guns (TWS II) which happens to also be a third lighter – is an example; developing a dual purpose undergarment aimed at protecting from the fire and the extreme cold, like the FROG, is another one (see the interview); enlarging the soles of the Marines’ boots “to ensure better stability and improve comfort” as stressed by Lieutenant-Colonel Pasagian, is another one: in this area, “the new aim is to leverage civilian advances in design and materials to build or buy new boots that are more comfortable, longer lasting, and support the efforts of troops in the field (…)” (see: US military Combat Boot Orders, DID, July 13th, 2009);

- looking towards the future in a sustainable development mindset is certainly likely to kill more than two birds with one stone: whether designing new hydration systems (armoback hydration systems for instance) or searching for viable fuel cells, many industries worldwide – defense and non-defense – are actively working on finding breakthroughs in these areas. Since “70% of the tonnage required to position the US Army into battle is taken up by fuel”, fuel cells and other energy devices (such as an Australian vest generating energy from body vibrations) could indeed revolutionize the battlefield (see: Military Forces Move into Power, January 16th, 2009). So could an innovative wastewater treatment system called DAAB: developed since 2008 by the US Army and the Texas Research Institute for Environmental Studies, it should be deployed in Iraq in 2010.

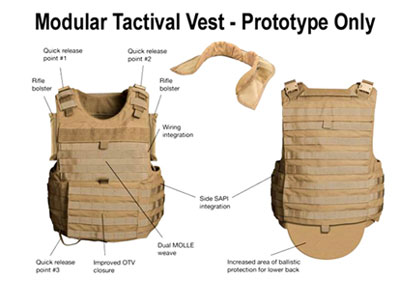

Keeping these goals in mind, for Lieutenant-Colonel Pasagian, one of the most rewarding recent improvement has been made in the area of body armor with the introduction of the Modular Tactical Vest (MTV) in the USMC. Follows a narrative of the above-mentioned interview.

Cpl. Brian Aldrich remains vigilant during a security patrol in support of

Operation Pathfinder, Feb. 9, in Farah province, Islamic Republic of

Afghanistan. Aldrich is a fire team leader with Company I, 3rd Battalion,

8th Marine Regiment (Reinforced), the ground combat element of Special

Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Force – Afghanistan. SPMAGTF-A’s mission is

to conduct counterinsurgency operations, with a focus on training and

mentoring the Afghan national police (Marine Corps Photo by Lance Cpl. Monty)

***

THE INTERVIEW

GOING MODULAR ON BODY ARMOR

[SLD] What have been the major recent evolutions of the USMC infantry combat equipment?

– In regard with the Iraqi war

– In regard with the resetting from Iraq to Afghanistan

– Are there identifiable phases of evolution (depending on threat, availability, technology, etc)?

[Lt-Colonel Arthur J. Pasagian] In the past, Marines’ protection was limited to helmets and flack jackets, which resulted in fragmentation projectiles’ injuries in conflicts like the Korean war. Today the pace of development in this area has quickened, especially in the past six-seven years in the context of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). It started in early 2000, when technological advances were made to stop small gun rounds and projectiles. Improvement has been made since then and protection against small arms in particular has been enhanced thanks to hard plates. The war in Iraq has been requiring extra-fragmentation protection and lead to the most significant advance to this day with the introduction of the Modular Tactical Vest (MTV) last spring: what makes the MTV especially attractive is its complex load distribution system and multiple adjustments options for threats, but also weather conditions.

The flexibility the MTV offers allows the warfighter to tailor the appropriate level of protection to the threat whether IEDs or else via the mix of hard and soft armour. It is cold-resistant and is designed to provide a full-body level of protection.

To address flame threat, body armour has been combined with Flame Resistant (FR) technology and gear for some time: we went from using traditional FR materials/fabrics/products, such as flight suits circa 2000, to developing specific products for infantrymen: hence FROG, a 4th generation flame resistant gear in service since 2006. Worn underneath the vest, the suit is made of a mix of dissimilar material, including kevlar. The problem has been dealing with the heat generated by the extra-clothing and to find the right balance. On the other hand the mix of cold weather flame resistance has been very successful and especially appreciated in the Afghan winter and spring, thanks to a thermo-managed system that is also flame-resistant. This innovation happened to be a real breakthrough in 2008 and it was decided to field the entire force with it.

Making the vest water-resistant has been another challenge, but a crucial life-saving asset.

Master Sergeant Ilich Bello of PG16 wears the entire Flame-Resistant

Organizational Gear ensemble including the Lightweight Helmet,

goggles and Modular Tactical Vest.

(Photo by Bill Johnson-Miles, USMC, June 2009)

Lessons learned from Afghanistan are being “fed directly to the gear”: they have brought back very valuable feedback rather rapidly which contributed to improve R&D on 3rd generation plate-carriers. Higher elevation constraints have been translated into lighter plate-carriers and a better product able to manage thermostress and humidity.

Is there a “typical” USMC infantry combat equipment?

– Right now the missions are mostly land-based vs amphibious: how does one handle a potential shift in mission in terms of gear and training?

– Is there a joint approach for land gear or is USMC equipment rather different than Army’s and other services?

A “typical load” for the Marines has two major specificities: it has to be flame-resistant and it has to have body-armor (plate-carrier; MTV). Then one has to add the usual load: ammunition, batteries, water, eyewear, radios etc … The Marines’ gear is mostly identical to the Army’s or the Air Force’s: what differs though is the way it is carried.

However the amphibious characteristic of the USMC brings about a fundamental difference which is the requirement for reliable emergency release, which tends to be tested separately, but otherwise the JCIDS (Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System) develops capabilities on a joint basis and all services go through the same testing process. The MAGTF’s unique amphibious nature also tends to generate more focus on making the gear lighter, more agile and maneuverable, sometimes more lethal: MARSOC (Marine Special Operations Command) is in charge of developing special tailored equipment.

The main goal is a baseline for autonomy: from this point of view the plate-carrier and the MTV constitute two complementary customized solutions, resulting from the new recognition that one does need to adapt to a very dynamic environment. In the longer term, a modular system may emerge with more commonality with other services.

What have been/are the major challenges encountered?

– Weight issue debate

– theater-specific adjustments, such as hydration for instance?

– manufacturing issues (e.g. preventive withdrawal of ESAPI in February 2009; helmet bolts exemple in May 2009; enhanced quality control; etc)?

The debate about lightening the load has lead to going “back to basics” and has stressed the limits of technology: an increased survivability and mobility come at the expense of a reduction of the level of coverage with a 10 to 12 pounds diminution in overall weight. Not all Marines are fully loaded to the max, but some of them have indeed to carry up to 75 pounds of gear (coms; water; etc), including 30 pounds body armor.

As far as water is concerned, systems are getting better and better with the development of filtration kits.

Regarding manufacturing and testing, the highest quality is sought and the Marines do their own additional testing. Fielding decisions are done in government facilities and product development is usually not outsourced. A team effort exists which starts in Quantico, with the Marine Corps Combat Development Command defining the requirements for the force . In the case of the plate-carrier fielding, an urgent need requirement was determined for Afghanistan in 2008: it took only four months for the whole three-step process of requirement assessment, test standards in government labs including balistic testing (which usually last 90 days), and quality control to be accomplished, so that a surge capacity of 10,000 plate-carriers (out of 2,500) could be achieved. Such a speed process – even in the world of urgent operational needs — has rarely been heard of as far as non COTS items are concerned.

How does one keep a balance between the need for additional capabilities and agility/simplicity?

– How is it decided? Via lessons learned process or do commanders on the field have a certain latitude and autonomy on such decisions?

Available protective systems are complementary and the military decides on the field of what is appropriate depending on the mission profile: the Commander in the theater is the one choosing the options and side-plates at the Lieutenant-Colonel level. It is his choice to leave some optional gear at the base in order to tailor the load of each combatant to a unique mission. It has of course been tested beforehand and the Commander can adapt it depending on the need: an offensive mission will require more maneuverability, hence only the vest/plate carrier might be used in these scenarii, consequently lightening the overall load by some 10 to 12 pounds.

In a Distributed Operation decentralized environment characteristic of the USMC as a “sizable air-ground task force”, the decision-making process goes down to the battalion Commanders.

What are the logistics and support aspects linked to modern combat infantry gear?

– Supply for water, food, energy, other needs?

– Repair and support of specific gear?

– Evolution over the past years?

– Typical log challenges, issues, solutions and/or need for improvement?

Logistic support within Marines units have followed the same trend towards being more distributed. In order to ensure a “safety level of supplies”, the system must remain as simple as possible with issue points for reload.

The main challenge as far as body armor is concerned is the examination and the control of the plates: the latter are being x-rayed before deployment in the context of a comprehensive 18-month program. In addition total visibility asset is being pursued with the planned introduction of unique identifiers (UIDs).

Is there a different training required to match evolving equipment?

– e.g. extra-strength training or regarding higher-tech gear?

The new flexibility involved in latest generation gear – such as front commands to release slide plates – implies new reflexes to become secondary nature and new training practices which are included in the Marines’ manual. Contracts usually include new equipment training : emergency release, water kits and battery/power system are all examples of different procedures to acquire. The best trainers from this point of view are the makers of the systems themselves. That is the case for the vest, which is a rather recent adoption, since it was newly discovered in 2001: maintaining the plates properly, making sure they are good plates are all essential conditions for success.

The load bearing Modular Tactical Vest optimizes the same Outer Tactical Vest (OTV)

ballistic protection, wears more comfortably than the OTV, and enables Marines

to easily configure components of their combat load

to best meet specific mission requirements. It also includes a better quick release system.

(credit: Dedra Jones, USMC, June 2009)

As far as the discussion over weight-caused injuries goes, the USMC has not recorded a trend of higher injury rates because of higher gear weight, since this factor and austere environment conditions have traditionally been taken into consideration in the basic training of any Marine: physical fitness has always been especially hard and part of the territory of being a Marine. A new component of Marine fitness programs is being implemented to “heighten awareness” and better match physical fitness with the operational environment. The Combat Fitness Test (CFT) is intended to keep Marines ready for the physical rigors of contemporary combat operations. The CFT has been implemented recently as part of keeping the USMC mantra “sharp mind, sharp body” going. Moments of rest are of course planned, as the Marines are riflemen first.

Weight is not a new issue and not enough data are available to draw the proper conclusions. However, all is of course being done to minimize it from lowering the carriage down to the waist, playing with various pack sizes and ensuring proper levels of hydration. Adjustments are also being made at other levels, such as boots, which are conceived to bear wider and on more rugged terrain: with a two-year durability, they tend to be more expensive, but considerably better.

From that point of view, the improved version of the MTV has lead to major changes in a very short time and looks like the right polyvalent solution regardless on where troops may be deployed.

Sgt Maj. David Bradford, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment sergeant major,

and Staff Sgt. Justin Bradley talk about security improvements,

implemented in Delaram, Farah province, Afghanistan. Bradford and Bradley are coordinating

with the Afghan national police to increase security for Delaram citizens.

Insurgents had then been targeting the area using suicide attacks and attempting

to harm civilians by planting IEDs in the bazaar area. Bradford and Bradley are part

of the Ground Combat Element for the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force-Afghanistan.

(Photo taken in March 2009 by Chief Warrant Officer Philippe Chasse)

source: www.marines.mil/unit/2ndmlg/Pages/news/2006/Protective%20gear%20keeps%20Marines%20safe.aspx

———-

***Posted January 11th, 2010