By Robert Johnson

U.S. Army Soldiers from 1st platoon, delta company, 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment conduct a mounted counter indirect fire patrol in Sabari, Afghanistan (Courtesy Photo: Joint Combat Camera Afghanistan, Coalition Outpost Sabari, Afghanistan, 01/15/10)To be Tracked or to be Wheeled: A False Debate?

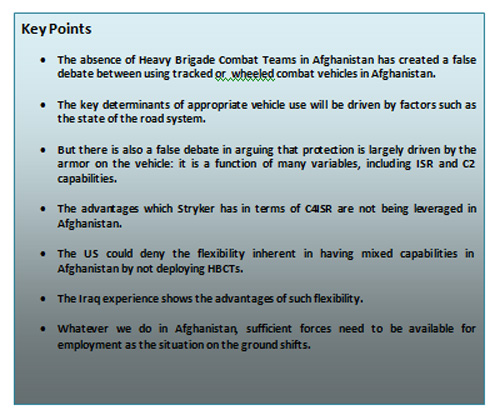

There is a debate simmering “under the radar” between different camps, mostly within the U.S. Army, concerning which is best suited to meet the demands of combat operations in Afghanistan: tracked or wheeled combat vehicles.

Unfortunately, both sides fail to address several key issues. The discussion, which pits the Stryker vehicle against the tracked vehicles of heavy brigade combat teams (HBCT) (such as the Abrams tank and the Bradley fighting vehicle), is often cast in terms of which vehicle offers the better set of protection vs. mobility trade-offs.

While clearly the heavier HBCT vehicles offer greater armor protection and off-road mobility, Stryker enthusiasts argue that the Stryker, with its greater speed and add-on armor, matches or exceeds the HBCT vehicles in terms of effectiveness in Afghanistan combat operations. In truth, the argument is essentially conceptual in nature at this point, given that the U.S. military has not yet deployed HBCT formations into Afghanistan.

The reason for the absence of HBCTs in Afghanistan consists of a combination of the following factors:

- HBCT formations remain heavily committed to operations in Iraq;

- Deploying heavy vehicles into Afghanistan will prove difficult (i.e., either completely by air or via the Khyber pass from the Pakistani port of Karachi) making the Stryker (sans add-on armor) more strategically deployable into the country; and

- As some HBCT advocates have suggested, the U.S. Army favored giving the Stryker an opportunity to demonstrate its effectiveness as a way to secure the future of Stryker formations.

- The absence of heavy U.S. military land units in Afghanistan stands out as some allies, most notably the Canadians, have for years deployed heavy tracked land forces (i.e., with both tanks and APCs) as their contribution to NATO forces in country.

Enhanced Protection: Much More than Meets the Eye

Despite these considerations, the debate between Strykers and HBCT vehicles tends to cloud the more relevant and important factors that should determine what formations are best suited to enable combat operations within Afghanistan.

-

First, the state of the road network in theater is best described as abysmal.

As some have said elsewhere, the best roads in Afghanistan are worse than the worst roads in Iraq (and the worst roads in Iraq are worse than the worst roads in the U.S.). Therefore, it would seem reasonable to conclude that a stronger off-road capability would be a plus. This assessment appears to have been validated by the MRAP program’s special acquisition of MRAP all terrain vehicles (MATVs) for deployment to Afghanistan. These vehicles are equipped with independent suspension technology. In this regard, the advantage would seem to belong to the HBCT vehicles. -

Second, protection is much more than simply using armor to stop IEDs, RPGs, or whatever the Taliban may throw at allied forces.

This observation should not minimize the role of armor protection – witness the up armoring of Humvees in Iraq and their ultimate displacement by MRAPs. It should, however, highlight how armor protection remains the last line of defense in terms of soldier protection.

Most importantly, sophisticated sensors and systems provide battlefield commanders with the intelligence and knowledge of where the enemy is deploying and what they plan to do. These capabilities, called alternatively ISR and RSTA by U.S. and European militaries, provide the first line of defense.

The second and third lines of defense, given the integrated nature of combat capabilities, are the firepower and mobility of the vehicles themselves. For instance, the ability to shoot and destroy an enemy system or simply to drive your vehicle where the enemy is not or cannot go, constitute additional elements in providing protection to friendly forces.

A fourth line of defense is access to a robust network, enabling utilization of key combat multipliers, especially air (rotary and fixed) and artillery and mortar fires.

Given this more comprehensive understanding of what constitutes protection, HBCT formations have an edge when assessing their added armor protection, greater firepower, and superior off-road mobility. The Strykers, on the other hand, have an edge in terms of ISR capabilities, given their advanced on board C4 architecture that enables more sophisticated networking with ISR assets and other combat multipliers. Depending upon the relative emphasis one places upon the different capabilities contributing to protection, one could fairly claim either set of vehicles as superior.

U.S. Army Soldiers from 1st platoon, Delta company, 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment conduct a mounted counter indirect fire patrol in Sabari, Afghanistan (U.S. Army Photo by Sgt. Jeffrey Alexander,Joint Combat Camera Afghanistan, Coalition Outpost Sabari, Afghanistan, 01/15/10) -

Third, there are a couple of overlooked issues specific to Afghanistan that are crucial to understanding the success or failure of the employment of heavy or medium weight land formations in tactical operations.

Specifically:

– The connectivity from theater to home station in the past and today (unlike in Iraq) remains virtually non-existent in Afghanistan. Therefore, Stryker formations are unable to utilize their superior on-board C4 architecture to establish a number of network-based advantages when preparing for on-going operations.

– The networks within theater (i.e. within Afghanistan) are not as robust as in Iraq nor are the information platforms (like UAVs, etc) as plentiful in Afghanistan as they have been in Iraq.

These key factors explain why Stryker formations in Afghanistan have been unable to capitalize upon their superior on-board C4 architecture not only to enhance their protection, but, more importantly, to become more effective in their mission.

On balance, these factors create more of a disadvantage for the Stryker formations than the HBCTs, which, absent the more advanced on-board C4 architectures, are a more self-reliant formation in terms of the mobility, armor protection, and firepower components of protection.

A couple of additional factors, both of which are not measurable without specific experience in Afghanistan include:

-

(1) the relative quality of leadership of each particular formation;

-

and, (2) the quality of preparation and training for deployment to Afghanistan.

The Stryker formations that have thus far deployed to Afghanistan shifted at the last minute from a planned deployment to Iraq making their preparations cursory at best. HBCTs, as already noted, have not yet deployed to Afghanistan.

These two additional factors are crucial considerations, but – given the current state of the Afghanistan experience – not yet measurable, in terms of HBCTs vs. Stryker brigade formations.

Mixed Capabilities: the Key to Flexibility and Effectiveness

Finally, as almost all combat soldiers recognize, to argue that one single type (or even class) of vehicle best serves the needs of combat operations in Afghanistan, misses one of the most important elements of conducting combat operations.

Organizing different units together to achieve a mix of capabilities most suitable for the current combat operations is a long-standing and widely recognized approach. Such an approach enables the combination of capabilities to optimize effectiveness.

A great example of this aspect of combat operations occurred in Iraq with the very units being considered here. When then LTG Ray O’Dierno commanded the multi-national combat formations in Iraq during the recent surge, one key component of allied forces’ ultimate success was the task organization of the HBCT and Stryker brigade formations to suit the urban nature of the combat operations. In particular, Abrams tanks were moved out of the HBCT formations essentially parking them outside the urban areas. This move made the Bradley the primary vehicle weapon platform due to its superior precision and less damaging fires. The Strykers were then added as combat troop transports based upon their speed and relative ease in navigating urban area road networks. This approach was designed to more effectively conduct counter insurgency operations in urban areas where extensive collateral battle damage jeopardized the objective of earning and retaining the support of the populace, while at the same time still bringing superior firepower and mobility with sufficient protection to the battle itself.

Armed with this understanding, one must wonder why the U.S. military continues to deny itself the ability to provide battlefield commanders with a similar set of flexible options, in terms of task organization opportunities, that would come with the deployment of both Stryker brigades and HBCTs into Afghanistan. Additionally, why have they been slow in building a robust network that connects units within the theater, as well as with those outside the theater? And why have they been so slow in adding ISR assets?

It would be unreasonable to conclude that the U.S. military has failed to consider these factors. Nor would it be appropriate to consider that the Administration has not allowed the U.S. military in Afghanistan, within an overall limit on the size of the surge, the mix of forces that they would request. For example, this happened when then SecDef Aspin denied the U.S. military’s request for tanks in Somalia in 1993; the impact of this move cannot be lost on many senior Obama Administration defense officials who also served during the Clinton Administration.

Building a Hedge Capability in Afghanistan

Clearly the answer lies in the type of combat operations the allied military leadership in Afghanistan plans to conduct. Afghanistan, all agree, is not the same as Iraq and therefore the lessons of Iraq are not readily transferred. In particular, given the difficulties noted above in mobility over land (not only in terms of deployment, but also in the logistical support of heavy units), unlike in Iraq, air operations – in terms of combat firepower, ISR, and lift – can be expected to figure most prominently in Afghanistan.

In such a case, light infantry and special forces – capable of vertical operations (i.e., air insertion and resupply) – can be expected to figure prominently and, perhaps in the leadership’s mind, decisively despite the challenges presented by the extreme altitude of certain areas of Afghanistan.

Such thinking is evident in the appointment of GEN Stanley McChrystal, a career special operations and light infantry officer. Perhaps, the war plans have so few heavy forces committed to Afghanistan because the campaign envisions decisive combat power being delivered via a combination of air and light infantry /special operations forces.

If correct, then the lack of HBCTs in Afghanistan and the relative shortage of tactical and operational mobility assets capable of transporting vehicles begins to make sense. However, it remains to be seen whether key terrain can be held effectively over the long term by light infantry forces supported by air power.

One must also consider what Iraq War experience might transfer more readily to Afghanistan. For instance, immediately following the declaration of victory in Iraq by President Bush, sufficient numbers and types of U.S. troops were not effectively employed, rapidly transforming the U.S. “victory” into a protracted counter insurgency campaign. One lesson from Iraq that can be applied to Afghanistan is that whatever we do in Afghanistan, sufficient forces – in terms of both numbers and types – should be available for employment as the situation on the ground shifts.

If anything is constant in war, it is that, as Clausewitz opined centuries ago, because the enemy is an independent actor, “the simple becomes very hard.” This would suggest that perhaps a few HBCTs might have utility in Afghanistan, if only as a hedge against the dynamic nature of warfare.

———-

***Posted January 25th, 2010