SLD conducted an interview with Lieutenant General James Dubik in early February 2010. As one of the key implementers of Iraq policy during the surge period which is allowing a transition policy to be conducted in Iraq, General Dubik is one of the most qualified persons to discuss the challenges of ongoing change in Iraq.

Lieutenant-General James M. Dubik assumed command Multi National Security Transition Command-Iraq on 10 June 2007 and is now a senior fellow at the Institute for the Study of War, which he joined in 2009 as a senior fellow and where he has authored several notable studies and assessments on Iraq and Afghanistan . Previously, LTG Dubik was the Commanding General of I Corps and Ft. Lewis. He was commissioned a second lieutenant of infantry from Gannon University as a Distinguished Military Graduate in 1971. He retired from the service on September 1, 2008.

There is no better person to discuss the challenges facing the transition in Iraq in 2010 and 2011 than General Dubik. Sldinfo is shaping a series looking at the challenge of defense of Iraq in the post-2010 period and General Dubik’s interview is the lead piece of that effort (See: Second Time Around, an Army piece on a soldier’s second time around in Iraq, which provides a measure of the progress discussed by Lt. General Dubik).

***

SLD: General, before we discuss your Iraq experience, could you tell us about your background and prior experience?

General Dubik: Two aspects of my background were most relevant to Iraq. First, my intellectual background is philosophy, and especially political philosophy. Second, my professional background is in the Army infantry. I am a paratrooper. I’ve been with a Ranger battalion six and half years, with the 82nd Airborne Division for four years. I also have significant command experience with the 10th division and the 25th division and was commander of I-Corps. I have seen operational experience in Haiti, Bosnia, and Iraq. I also was tasked by the Chief of Staff of the Army to stand up the First Stryker Brigade in 1999 and 2000.

All of these things – broad political understanding, wide-ranging operational experience, and shaping innovation in introducing the Stryker – came into play in shaping my approach to my latest Iraq deployment in May 2007.

SLD: How would you characterize your initial entry into the Iraq assignment in 2007?

General Dubik: General Petraeus had just been there and General Odierno was already in command of the Multi National Corps. Ambassador Crocker had just arrived. I was the last of the senior members of the leadership team to arrive. I visited the country prior to taking command and discovered that the situation was as dire as people believed. It was not misreported at all.

We also had a sense that if we didn’t turn it around by the end of that year, quite frankly, by September of 2007 (as General Petraeus testified) if we didn’t have empirical evidence that it was starting to turn around, there was a very real chance that our mission would be “withdrawal under pressure.”

And so we worked really hard as a team:

- Ray Odierno on the counteroffensive and partnering with the Iraqi Security Forces

- General Petraeus and Ambassador Crocker on governance and economic improvement at both the national and provincial levels as well as overall policy

- and myself on accelerating the growth of the Iraq security forces in size, capability, and confidence.

SLD: What were your expectations in terms of the core tasks that you were facing?

General Dubik: Well, I knew that I would be responsible for training and equipping the Iraq security forces, and continuing to develop the ministries of defense and interior. And I had a very extensive set of conversations with my predecessor, Marty Dempsey; we have been friends for a long time. Our preparatory conversations probably extended for five months. We had video conferences back and forth between the two of us, as well as with his subordinates.

SLD: So it was good hand-off operationally?

General Dubik: It was a very good. In addition, I read probably 20 new books and reread 15-20 old books on insurgencies to get myself intellectually and culturally prepared. But I really didn’t have a sense of the direness of the tactical situation until May of 2007 when I flew around the whole country. I took one month of orientation before the change of command and flew, literally, as far south as Basra, as far north as the Syrian border, and every place in between. I saw how much we had to do and how little time we had to do it. It was a pretty daunting.

SLD: You worked the training hand in hand with the counter-insurgency operations. And the counter-offensive played a key part in shaping the Sunni Awakening and the Sadr cease-fire. In your view, did the counter-offensive provide a necessary but not sufficient condition for shaping a successful training mission?

General Dubik: I had extensive conversations in the period of the counter-offensive with General Babaker, Chief of Staff of the Iraqi Forces, as well as the Defense and Interior Ministers with regard to how to build up their forces. This was a dialogue and a shaping effort to determine what would work. The counter-offensive created the trade-space within which we could shape the new Iraqi forces. “Trade space” in this sense: we knew that we could not just crank out numbers and ignore quality, but we also knew that we could not wait until we got the top quality soldiers, leaders, and units. We’d lose the war either of these ways. So we determine what “sufficient” quality was relative to the enemy and the time. We focused on building a sufficiently large, sufficiently led, and sufficiently competent security force. The success of the counter-offensive helped increase recruiting and retention. It also improved confidence.

There was a clear desire on their part – all three of them – to grow the Iraq military, primarily at this point, in 2007. And to grow the national police much faster than we had originally envisioned.

SLD: What role did the Sons of Iraq play in all of this?

General Dubik: They played a big role. They were one of the consequences of the Sunni Awakening. The Sons of Iraq began to provide security at the local level. At this stage, it was always in conjunction with coalition forces and Iraq forces. Rarely were they operating independent of those. That was part of the partnership that Ray and I had in shaping a joint strategy. He had to oversee these guys on the ground, and most of them joined the police forces. So my role was to help Minister of Interior Jawad Al-Bulani figure out the way to get these guys properly vetted and then hired into the police force. At times it was a torturously slow process, but the Minister got about 10,000 Sons of Iraq into the Iraqi police.

SLD: As you did the ramp up of the new security forces, how did you reach out to the former Army officers during the time of Saddam Hussein?

General Dubik: General Babakar and Defense Minister Abu Qadir had to reach out to former officers and sergeants to bring them back in. They were the prime movers in this effort. Now they did this with proper vetting, and they did this with proper retraining, but they could not have grown their forces without tapping into that former expertise.

Minister of Interior Bolani also developed a program for reaching out to former army officers to bring them in as police officers. Because as he grew the police force to almost 300,000 by the time I left (July 2008), he had to grow an awful lot of police officers, and initially they had only one way to produce them, and that was the three-year Baghdad Police College. He realized that the production rate of a three-year college was not going to be sufficient to get officers for the size of the police force he was building. So he reached out to former police and army officers as well. Again, properly vetted, retrained, and placed. And he expanded the capacity of the Baghdad Police College, increased the ways in which a person could become a police officer – instituting programs for police NCOs to enter the officer ranks, shorter programs for Army officers who wanted to convert into police, and accelerated programs for police recruits who already had an education.

SLD: In effect, you were working with the Iraqis to shape both from a bottom-up and a top-down point of view, a new authority structure?

General Dubik: Yes, and in our discussions with the Iraqi government we focused on the right sizing of the force to be able to provide for internal Iraqi security. In my discussions with the Iraqi Prime Minister, I suggested that he would need a force of around 600 to 650,000 to secure the country. He was initially taken aback and he said: “Do we need a force that big?” And my answer was “Mr. Prime Minister, if you want to secure your own country, this is the force you are going to need. Later, as security improves and the economy grows, you can cut back on the size. Or you can stop at any level if the situation permits.”

SLD: Where did the number you were suggesting come from?

General Dubik: It was based on a conjunction of several inputs. One was done by the Center of Army Analysis. They are here in DC. I asked General Petraeus’s staff to provide the right assumptions, that way it would not appear that I had “cooked the books,” so-to-speak.

So, Center of Army Analysis did one. Then I asked General Odierno’s staff to do a commander’s assessment. Then I asked the Minister of Defense and Interior what their assessment was based on their own analysis of their country.

And then last, I asked my predecessor, Marty Dempsey: “You’ve done this now for almost two years, what’s your assessment?”

All these assessments congealed around somewhere between 600 and 650 thousand. And when you have several different groups come up like that with a virtual consensus on the number, that’s a very powerful argument.

SLD: Presumably this number and approach was being shaped for the transition to a self-defense force, not one just able to do internal security, is that correct?

General Dubik: Yes, for the longer-term you would re-shape or transition the force built to succeed in the counterinsurgency to one that can defend the territorial integrity of Iraq. You’re going to want to reduce the COIN force and separate the military from the police because internal operations of a country should be run by its police, not its military. And then focus the military on external self-defense. That’s not the position we were in at the time, though. To get to that position, you need to build 600-650 thousand security forces as quickly as you can. Secure your own country, and then that’ll set you up to have the possibility of successfully refocusing later on. The good news is that we’re at the transition point now. We got there.

Q: How about the problem of equipping this force? What was your approach? I cannot imagine this was and is an easy process.

General Dubik: To grow the force as quickly as we did, and accelerate this growth, we decided that the first thing that we had to do was identify what was the minimum combat essential equipment necessary to win the war we were in.

To make sure we got 100-percent of that, the rest of the stuff we could defer, and then we could identify some longer-range things that they would need for external defense later on.

We were not going to slow the growth of the force necessary for internal security at the expense of buying something that wouldn’t be necessary till 2025. Finally, we were going to disintegrate growing the force. That is, we would let each element of the force – for example, intel, maneuver, logistics, aviation, fire support – each grow at the fastest pace it could. That way, we would not slow down one element because of another. An integrated approach is always optimal, but when you’re in a war the sub-optimal is often the best course of action. That was a big decision.

The second decision was what part would the U.S. pay for and what part would the Iraqis pay for? In November 2006, so just a few months before I showed up, there was the crossover point in investment in Iraqi security force. By that I mean, at the end of 2006, Iraq was starting to spend more for their own security forces than Congress had appropriated in the Iraqi Security Force Fund final. My predecessor had set this up.

Then from the end of 2006 to present, the gap between spending just got larger and larger. By the end of 2008, for example, the aggregate of Iraqi Security Force Fund was $22 billion. And the aggregate of what Iraq spent on themselves was $22.8 billion. So, even in the aggregate, by 2008, they were starting to spend more.

SLD: Did oil revenue play a part?

General Dubik: It’s a very big part. And that’s why part of the overall counterinsurgency strategy was to increase the oil production so that they could keep paying for their own stuff. But the Minister of Defense, the Minister of Interior, General Babakar, and I all had to come to an agreement concerning who’s going to pay for what in this acceleration. We used the Iraqi security force funds in those conditions where we had to buy something very quickly, so we could keep the pace of growth. And we used Iraqi funds for much of the support and logistics, some near-term items, and some of the longer-lead items.

SLD: How were you able to address the U.S. funding or acquisition side of this in a very fluid situation?

General Dubik: We used Congressional provided Iraq Security Force Funds to buy the stuff we needed quickly. We bought the small arms, individual soldier equipment, some larger equipment, radios, night-vision devices, trucks, some humvees. But things that we knew we could turn over quickly, we bought with Iraqi Security Force Funds.

Things that we would have to take a little bit longer, or the rest of a unit’s equipment – beyond the minimum combat essential list – the Iraqis bought. So for every unit, we had to determine: OK the U.S. is going to spend this, you’re going to spend that. And then we had an agreement and it worked out relatively well for the acceleration plan. Not perfect, but “good enough.”

By identifying minimum combat essential equipment, we were not wasting money or time on equipment that was necessary, but not necessary for the fight immediately. For example, if a unit needed 12 trailers for its full equipment list, but they didn’t need 12 trailers to fight right now. We would say, “Minister, you buy that, and we’ll buy the stuff that we really need for the near-term fight. Because it was in our interest to grow this force as quickly as we did, not just their interest.

SLD: In this period, where were they buying the equipment from?

General Dubik: Mostly the United States, but not exclusively.

SLD: What about the role of Foreign Military Sales or the FMS system in providing equipment in this period?

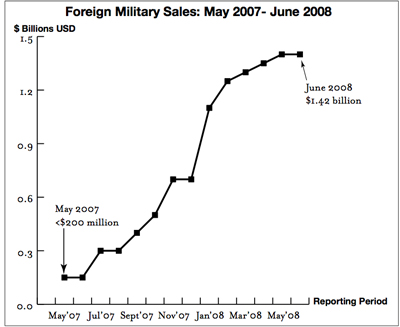

General Dubik: Well, at the start, while I was probably the loudest complainer of FMS initially, I have to acknowledge that the FMS process, once it was energized by the Secretary of Defense, through the stimulation of Senator Jack Reed and others, once it got energized, it really was amazing.

We went from receiving only $100 million worth of equipment delivered in the early summer of 2007 to I think, $1.4 billion by the time I left. So that’s – that’s a huge improvement.

They went from an average of about 120 days to process paperwork to 60 days to process paperwork. So, you know, again, the FMS process was still way too slow and not agile enough, in my opinion, but it did get better. Under the pressure that the Secretary put on them, they really improved. Not sufficiently enough in my view, but I have to acknowledge the fact that there was significant improvement.