The Challenges Facing the Supply Chain: An Interview With Bill Anderson

The Honorable William C. (“Bill”) Anderson served as Assistant Secretary of the United States Air Force for Installations, Environment and Logistics as well as the Air Force Senior Energy Executive under President George W. Bush. Presently he serves as President and CEO of Endura Energy Solutions, a Pegasus Capital company.

***

SLD: The Administration in this constricted financial environment is clearly cutting back contracts to the prime contractors and for both the Clinton and Bush Administrations, the primes were asked to manage the supply chain. With the cutback in manufacturing contracts, obviously the pressure on the supply chain goes up and the ability of the primes to manage it goes down. So essentially how would you address the problems in this kind of context given your experience in dealing with supply chains in both the public and private sectors?

Bill Anderson: The government is making decisions based on the facts that are laid out in front of them – shrinking budgets, etc. As a result, they’re cutting back on acquisition programs, which means there’s less within the federal government pipeline to support the private sector. It is a bit amazing to me when I hear from folks inside the beltway saying: Where did the private sector supply chain go? It’s kind of simple…the commercial sector supply chain has right-sized itself to respond to current and anticipated future demand.

The private sector acted rationally based on signals from the government…shrinking demand from the customer triggers shrinking revenue flow as money available to buy stuff shrinks the program within the federal government. Then, of course, the supply chain reacts in the same fashion.

It’s almost as if the government expects the private sector to pick up for the reduction on the federal government’s side of the equal sign, if you will, and seems surprised that the private sector wouldn’t respond in the way it does.

The private sector is following what is a logical pattern. If there’s less business, there’s less people associated with it and it’s going to cause some pretty significant problems.

If I’m a private sector guy in a truly private sector world, I will respond by focusing my resources where there is the greatest opportunity for revenue, and I would think that in this particular environment, the place where the most significant revenue’s going to be is on the maintenance tail because older assets be tasked to remain in service longer than originally anticipated, driving more maintenance requirements, so that’s where I’m going to put my efforts because nobody’s asking me to build anything new.

How do you manage that? The answer is I think you’ve just got to figure out how to squeeze more capability our of fewer and older platforms and if you’re the supplier to the federal government then you are looking at dealing with a longer-term outlook that is signaling a smaller number of multifunctional platforms that can do a lot more stuff…and that suggests a much smaller pie to be available to the private sector participants in the defense sector.

And then you’ve got to bear in mind that as you move down that road, you’re going to end up with less creative people out there who will have the capacity to develop new stuff if you were ever to ramp up in the future. You’re in essence selling the future at this point or conceding the future is probably a better way to say it to a very different model than we’ve ever seen before with no real understanding by any of us as to the implication because none of us have a crystal ball.

None of us really at this point have the capacity to understand really what that means. We can all project that somewhere in the future we’re going to end up a day late and a dollar short on something.

There’s a problem looming out there. We don’t know what it is yet. But because we’re constricting or shrinking our talent pool and our manufacturing base, it’s going to come some day and it will come as a total surprise. Our reaction time will be sluggish as our bench strength in terms of talent and infrastructure will be non-existent. We’ve been to this dance before, but in a much slower paced world. We moved quickly; we made up for lost time. In the 21st Century world we need to ask ourselves whether we will ever have the time to catch up on what we are giving away today if we are ever put in that position.

SLD: The point is that if you’re cutting the manufacturing opportunities for new platforms, you can’t make the assumption that the supply chain is simply there as a ready capital pool for the government to tap as it wants. The absence of new platforms will essentially shrink the supply base available to meet your needs, that’s your point, isen’t it?

Bill Anderson: Right.

SLD: That’s simply a market logic.

Bill Anderson: Right.

SLD: It would seem that the interest of the subsystem providers and supply chain firms will find their interest elsewhere so, for example, GE is supporting the Chinese and building the commercial aircraft and the Chinese certainly have an interest in going into the market space with the A320 or Boeing 737. GE clearly is moving towards that commitment for the simple reason that they’re going where the work is. So you could well expect such movement with the larger suppliers, obviously the smaller suppliers are not in this position. The largest suppliers would clearly globalize and their globalization may or may not be in the interest of the federal government.

Bill Anderson: And not only are they going where the work is, they’re going where the customer is because the rest of the world will act in their own best interests, and I’m telling you what you already know. If I’m going to be a big buyer of something, I’m going to demand local production of those products.

Let me give you an example in the energy world; this one in the US. When I talk to state governors, they are saying, “Hey, I’m going to invest big in renewable energy. But guess what? I’m going to make sure we buy stuff that’s manufactured locally.”

So you’re going to see a shift to where the commercial sector is growing. You’re going to see a shift from military to commercial, at least in the U.S., the U.K., France, and Germany. But where do we expect to see the real growth in air travel and a corresponding demand for aerospace equipment? China, India and where do we think the manufacturers will go? But you’re absolutely right. The commercial guys are going to chase the opportunities that present themselves. If they can’t, they’re going to go out of business.

SLD: Your point is that they’re going to move to the local area to do that support, so two things happen. One is our major suppliers’ search for global customers and they displace U.S. jobs to foreign jobs is part of that global supply chain that they built.

Bill Anderson: Right. For two reasons. One is cost, and that’s obvious because you can build parts of a plane cheaper in China or India than you can in the U.S. or in Europe. But secondly, you will see customer pressure. You see it all the time where customers will not buy your product unless it’s local.

You saw this phenomenon manifest itself as Airbus worked its joint bid with Northrop Grumman on the tanker. Airbus certainly had the capability to build that machine in Europe. But, politically, if you are going to sell here you have to build here, have U.S. content you stand a much better chance of winning the contract and that’s just natural. Politically, every country will react in precisely the same way.

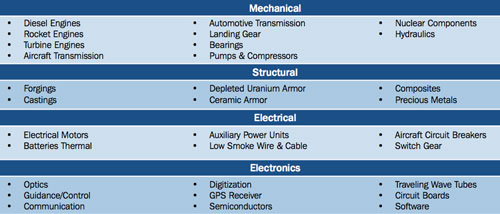

Source: DIB Segments and Subsegments,

Source: DIB Segments and Subsegments,

Defense Industrial Base, Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources Sector-Specific Plan as input to the National Infrastructure Protection Plan

Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, May 2007, page 5

SLD: You’d mentioned earlier that one response the supply chain could make staying in business is in modernization upgrades, but it doesn’t moving from performance based logistics raise certain questions about the ability of the supply chain to work effectively?

Bill Anderson: Did we ever truly have a competitive environment to determine where best value is for defense products, were metrics ever put into place to measure true performance output, whether goods and services come from in house or are outsourced?

In my mind, the answer is no. Did we really ever have true competitiveness in terms of making decisions on manufacturing, refurbishment, who manages the inventory, and then go through the entire supply chain, then make A76 (competitive outsourcing) in the context of system optimization and overall best value?

If the market is really responding like a true competitive marketplace, in some cases, things will be outsourced. In other cases, things will be moved in house. The latter seems to be a challenge in the current environment, but must be a real possibility if we are to find the best mix of activities and drive true competitiveness in an ever-changing world.

It’s dangerous when you say, and whether it’s the federal government that does this or private sector, because I’ve seen it happen in both, it’s dangerous when you’re going to say, “We’re going to outsource for the sake of outsourcing” or you say, “We’re going to insource for the sake of insourcing.”

The answer ought to be: We’ve done a full analysis and determined that in this particular instance, it is better to do this function in house or it’s better to seek an external supplier without edicts on which way to go and that leads to sub optimizing.

SLD: So you need a sound analytical judgment about the proper balance rather than being driven by an ideological position.

Bill Anderson: Absolutely and sometimes, you’ll do that analytical work and realize later that you made some mistakes in assumptions. That’s why these decisions should ebb and flow because humans make mistake and sometimes the facts change. The approach ought to be: What truly is the best value and provides the best performance in terms of material availability, equipment availability, and reliability in the ecosystem as a whole thereby best serving the needs of the warfighter? By the way, what might well be the best answer today could be a sub-optimized solution later. Therefore, there needs to be a clear process to undo or modify prior outsourcing decisions as mission effectiveness and economy dictate. Unfortunately, I don’t think A76 got us there.

The current initiative in my mind will not get us there either because it’s not an economic model that’s being driven by best business case analysis…and there is no real long term view as to capability viability down the road. It is ideologically driven. As you say, it’s either ideological or it’s politically driven, at least to some degree, in both cases. It doesn’t matter who’s sitting at the helm, there are political influences that get in the way that are blocking our vision towards good decision making.

Abstract from: Department of Defense,

Quadriennal Defense Review,

February 2010, page 82.

SLD: Several people in the administration are talking about the need to evaluate the critical skill sets we need for military production, military capability. Although that sounds good, I have some difficulty understanding if you’re not manufacturing and relying significantly on the private sector for the maintenance input, which shapes modernization, how does one do that?

Bill Anderson: I think the need is very real but you raise a valid point. You should also keep in mind, though, when you talk about manufacturing, you’re not just talking about building the next weapon system. We still have to, for example, make ball bearings and other replacement parts no matter if or when the next weapon system is authorized. Who’s looking at sources of raw materials, sources of manufacturing and design expertise, educational policies that impact the worksforce of the future, our scrap policy, as we assess the actual current and future health of our military production capability

Is the federal government capable of doing what you just described? Sure. Will it be hamstrung by politics or ideology and the answer won’t be optimized? I hate to sound crass, but probably.

If you would truly dedicate an independent group of expert manufacturers, and this country is full of folks who are some of the best manufacturing people in the world. Remember it was supposed to be Japan Inc. in the ’70s, but it never happened because there was a manufacturing renaissance in this country. Those people are out there. There are people who are capable of providing detailed analytics and thoughtful recommendations as you described while providing a very solid roadmap in my mind to what the right answer is.

Is that how it’s going to be done? If it is, great. In reality, will this talented pool of expertise be tapped to give us all a true look at what we are facing? Probably not.

If you can keep the politics out of it and get the people who really know in this country what manufacturing excellence is, I think you could have a great study with a great roadmap of how to bring the defense military manufacturing establishment to where it needs to be. And once we have an honest look at where we are and where we need to be, the efforts and costs associated with getting there can be balanced with other national priorities, and the American people will be able to clearly see the tradeoffs and balancing that will be done. Don’t get me wrong…hard choices always have to be made. They just are a whole lot more logical when made based on solid facts.

———-

****Posted March 29th, 2010