The USCG National Strike Force: A Key National Asset to Deal with Environmental Challenges

(Part Two)

SLD sat down with Commander Tina Cutter, Deputy Commander of the National Strike Force and Lieutenant Commander Tedd Hutley, operations manager for the National Strike Force, in mid-February of 2010. The National Strike Force is one of the United States Coast Guard elements to be affected by the budget cuts, and the key element being eliminated is the National Strike Force Coordination Center or national command element. This two-parts interview was conducted at the Head Quarters in Elisabeth City, North Carolina: it allows non-Coasties to understand what this command and the NSF does for the nation and how it will be affected by budget cuts.

***

The NSF responders : “Any Time, Any Place, Any Hazard”

“In 2009, a fishing vessel ran aground up in the Aleutian Islands and there was no oil spill removal organization

or organization that was able to take that job and remove the product off;

in this particular case, the Pacific strike team went up and had to utilize special Arctic classified hose

and multiple pumps to do this pumping job. They were up there for a couple of months.”

(Lieutenant Commander Hutley)

Credit Photo: Aleutian Islands Traffic, Vessel Traffic Overview,

Octobre 2009, www.aleutiansriskassessment.com

SLD: It looks like you basically have two different kinds of Con Ops in effect : one is to support a normal crisis or normal situation, supporting the federal coordinator and that’s most of what you do. But in addition you have to develop Con Ops for catastrophic events or high end events: you have to develop those Con Ops, the air delivered integrated package kind of response, working probably with the military, etc… One would assume that speed and reach are the most crucial assets in these kinds of situation, is that correct?

Commander Tina Cutter: We are not first responders: we are not like the fire department; so, although speed is important – it’s actually critical to us -, we are not going to ever be the first people on scene. However, the USCG and the federal government do not have much capability in this area. The ports and regions really need our guys, who are experienced, to go to all the spills around the nation; as spills become fortunately rarer, it is however more difficult to get that kind of experience. Since we are national and our teams augment each other, we do go everywhere so we do have it.

SLD: It seems that you’ve already dwindled down the number of folks capable of doing this, and that you’ve taken away a lot of the local or port oriented capability, is this a correct perception?

Commander Tina Cutter: Yes that’s true.

SLD: Now : we take away the port oriented capability; if we then threaten the ability to handle this on a regional basis – i.e. you essentially -, there is no local capability to go back to, if you undercut in addition the regional capability to manage these crisis: so it’s a double bad thing if your dwindling down the regional capability. Because of what you’ve done earlier for budgetary and rationalization reasons, this seems like a double rationalization that gives you at the end of the day, much more limited capabilities and perhaps eliminating an important skill set. Is that an accurate statement from your point of view?

Commander Tina Cutter: Yes, I think that’s true; the other piece of that is that, in addition to the reorganization that we did that has eliminated some of that, as well as the success of our inspections – where we basically eliminated substandard shipping from the United States -, there has just been less spills than there used to be.

SLD: So that means less oversight capability, isen’t it? If the commercial sector is left to regulate itself, isen’t there a risk of not going to be as effective as “mother checking on them” to make sure that their procedures are actually correct ? Or the risk that the private sector itself perhaps does not have the capabilities required to be able to comply with such procedures? So you may be faced with either a deliberate desire to not comply, or a desire to comply, but not having the regulatory oversight in execution. Regulations without folks to actually look at the actual capability and implement the regulations are more often than not unfortunately meaningless.

Commander Tina Cutter: You hit the nail on the head: as I mentioned before, we do have specialized equipment that does not mirror industry capability in the regulated community, like the Viscous oil pumping capability, and Tedd can give you some other examples.

Lieutenant Commander Tedd Hutley: I think when it comes to salvaging I agree: the enhanced Viscous oil pumping system was generated out of the spill in 1999 at a time when there was no pumping systems out there that could move that thick and viscous of an oil; and I do believe that because such a device was specially designed, we have that capability and industry doesn’t.

There are indeed often cases/jobs that industry cannot do, such as the one we just had this last year: a fishing vessel ran aground up in the Aleutian Islands and there was no oil spill removal organization or organization that was able to take that job and remove the product off; in this particular case, the Pacific strike team went up and had to utilize special Arctic classified hose and multiple pumps to do this pumping job. They were up there for a couple of months.

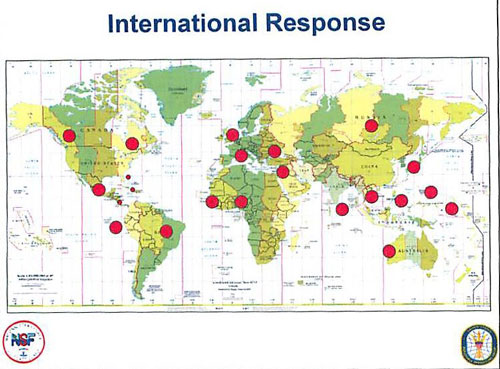

Commander Tina Cutter: We also support the Department of State on their request for international incidents and have a lot of experience responding internationally. We regularly exercise with the Panama Canal authorities for spill response. As far as our Pacific strike team is concerned, they’re all over: right now they are in Taiwan, and they are also doing a response in American Samoa.

SLD: One dilemma you seem to face is that if you do your job well in working with the private sector, you consequently respond directly less; and then folks might respond that you do not need to own your own equipment or kit to do the job, because we only need you sometimes. Although one could point out that those sometimes are the most damaging events. It’s kind of like a fire house, if you don’t have a fire you wonder why you have the fire house.

Commander Tina Cutter: That is the problem in a nutshell. And the elimination of the national command element could well lead to a reduction in core competencies in capabilities needed in a crisis. Current planning is to leave the three teams, but to get rid of the coordination center. So one of the four units, which makes up the NSF is being eliminated.

The problem is that if you take away our equipment, like in Alaska or in Hawaii (where is the other high end), you’d be taking as much as 75% of the ability to respond in an offshore or near shore environment. If you take away our equipment in the rest of the ports, it is one third of the ability in that port to respond in an offshore environment.

Another aspect about our equipment, that we haven’t even really touched on, is the fact that we are the only entity in the Coast Guard that has the ability to respond in level A to hazmat incidents.

SLD: What’s level A?

Commander Tina Cutter: The fully encapsulated suits, so that you can send people in a toxic environment. So there’s no other unit within the Coast Guard that has that capacity.

I think that the problem that we face is our teams are so busy, they are stretched out: we’ve done our own staffing study that’s shown that we could double our staff size and still not cover all of the daily work and training that we demand of our teams. And I think that when one looks at our equipment, which is aging and needs to be recapitalized, there is a reluctance to make an investment, because there hasn’t been a catastrophic spill since Exxon Valdes.

Lieutenant Commander Tedd Hutley: It looks to me that there are two incidents that define the situation well:

- Number one was the Cosco Busan oil spill that happened in San Francisco 2007 : it was a relatively very small spill in San Francisco Bay, but for that sensitive area, you would think that it was a catastrophic spill and there are some people that do define that as a spill of national significance for that reason.

- The second incident occured just last year : it was a tug and barge that ran aground on Bly Reef, the same reef that Exxon Valdes ran aground on. Now that wasn’t a catastrophic eleven million gallon crude oil spill like the Exxon Valdez, but that did occur even with the entire preventive measures that vessel traffic systems in place since Exxon Valdez.

Those, I think, are significant events: yes, there haven’t been huge massive catastrophic spills on a daily basis hard to justify, but you do have a very growing intolerance by the public for any type of spill – especially on the west coast, the North West and New England – and accidents do happen. Even with the entire preventive measures in place, you still had a vessel that just ran aground on that same reef that Exxon Valdes ran aground on. And we were involved in both of those cases, including doing the contractor monitoring for the tug that ran aground.

In the case of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, “the oil slick (blue areas) eventually

In the case of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, “the oil slick (blue areas) eventually

extended 470 miles southwest from Bligh Reef. The spill area eventually

totaled 11,000 square miles” (Source: Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council,

as quoted by www.eoearth.org (http://www.eoearth.org/article/Exxon_Valdez_oil_spill)