By Dr. Richard Weitz

Senior Fellow and Director of the Center for Political-Military Analysis at the Hudson Institute, Richard has joined SLD as a regular contributor: his current research includes regional security developments relating to Europe, Eurasia, and East Asia as well as U.S. foreign, defense, homeland security, and WMD nonproliferation policies.

One issue that has drawn less attention at this month’s congressional hearings on the Afghanistan War than in previous years is the narcotics dimension of the conflict. According to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Afghanistan supplies approximately 90 percent of the world’s consumption of opium—up from 70% in 2000 and 52% a decade earlier [1].

Although output dropped considerably in early 2001, when the then Taliban-led Afghan government enforced a ban on opium poppy cultivation to avoid UN sanctions, the chaos following the Taliban’s overthrow reversed this progress. As a result, Afghanistan has become the world’s largest heroin producing and trafficking country.

The illicit manufacture and distribution of drugs currently accounts for an amazingly large share (perhaps one-third) of Afghanistan’s economy. According to the UNODC, Afghan-based opiates now kill more people than any other narcotic in the world, approximately 100,000 people annually. The number of people who die from heroin use in NATO countries each year is more than 10,000, or five times greater than all the NATO troops who have died in Afghanistan since coalition began military operations there in October 2010. The Russian government estimates that more of its citizens die from using Afghan-based heroin every few months than perished during the decade-long Soviet military occupation of Afghanistan during the Reagan years.

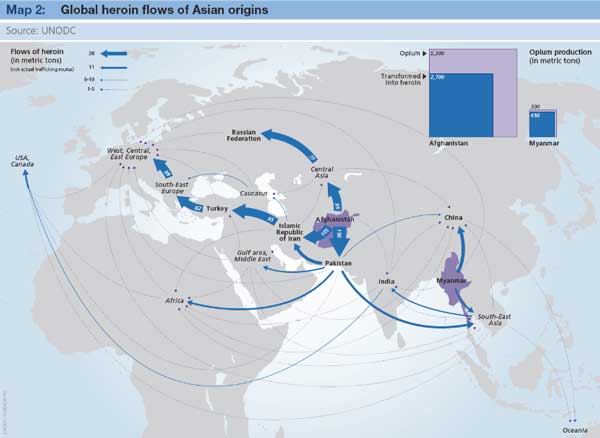

Determining the precise quantity of narcotics exports from Afghanistan is difficult but the UNODC estimates it to be around 3,500 tons per year. The primary routes run through Iran to Turkey and Western Europe; through Pakistan to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East; and through Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan to Russia.

While satellites can identify areas of opium cultivation, tracking the movement of processed opiates is much more difficult. Analysts can only approximately estimate the aggregate size of narcotics flows from intercepted drug shipments. Law enforcement officials also have incentives to exaggerate the success of their counternarcotics efforts.

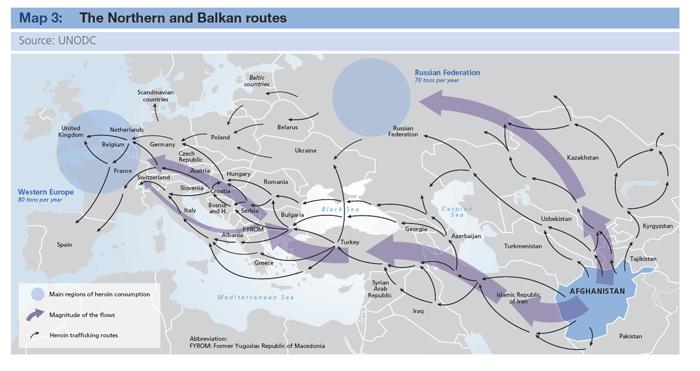

Source: Global Potential Opium Production, 1980-2009, World Drug Report, 2010, page 38

Source: Global Potential Opium Production, 1980-2009, World Drug Report, 2010, page 38

Nevertheless, the Afghan drug trade clearly represents a major international problem. Neighboring countries complain about the flow of drugs into and through their territories, which facilitates local narcotics consumption and corrupts their law enforcement personnel. Dealers throughout Europe and Asia rely on Afghan supplies of opium and heroin to satisfy local demand for these illicit drugs.

Improvements in local narcotics manufacturing technologies have resulted in a large amount of the country’s raw opium being converted inside Afghanistan into heroin and morphine base, which reduces its bulk tenfold and facilitates its movement through transnational narcotics markets. Illicit trafficking of narcotic “precursors”—substances like Ephedrine that are essential for the manufacture of certain illegal drugs and that must often be imported into Afghanistan – is also common.

Afghans also suffer from the drug trade. The narcotics industry is worsening many of Afghanistan’s other serious economic, political, and security problems, including its relations with neighboring countries. Illicit drug trafficking is draining resources away from legitimate economic activity and, by encouraging corruption and other fraudulent practices, undermining Afghan government institutions. Many Afghans are addicted to opium, while the pervasive narcotics industry spreads crime and corruption throughout the country.

The UNODC estimates that Afghanistan currently produces almost twice as much opium as is consumed worldwide. The UN believes addiction rates among Afghans have soared in recent years, with serious long-term health, economic, social, and security consequences.

There are only a few areas in the country where narcotics use is rare. Afghanistan’s poor health care and limited number of drug treatment facilities exacerbate this problem.

Of the $65 billion in revenue generated by the global heroin market, only a small portion goes to the Afghan poppy growers.

Most of the illicit profits go to those who convert the poppy into drugs, move them to foreign countries, or sell the narcotics to users. But the UNODC estimates that the Taliban insurgents derive several hundred million dollars annually from taxing opium growers as well as charging fees to protect the production and transit of narcotics and their chemical precursors through guerilla-controlled territory. They then use this revenue to purchase weapons, pay salaries, and bribe corrupt officials.

The UNODC also finds a correlation between the lack of Afghan government control of a province and its opium production, with the highest output occurring in the regions with the least security. At present, almost all the opium production occurs in six southern and western provinces of Helmand, Farah, Kandahar, Uruzgan, Day Kundi and Badghis – the same regions that have become strongholds of the Taliban insurgency. The U.S. military calculates that the Taliban and al-Qaeda receive up to 40 percent of their funding from the drug trade, while the UN estimates the figure to be closer to 60 percent. By encouraging narcotics trafficking and other illegal activities, moreover, the Taliban make the Afghan government of President Hamid Karzai and his foreign backers appear weak and ineffective.

The insurgency also indirectly stimulates drug trafficking by impeding anti-narcotics efforts in the affected regions. For example, eradication teams cannot travel safely through contested provinces. In addition, the fighting disrupts programs to encourage farmers to cultivate alternative crops or to prevent smuggling into neighboring countries. Besides the direct narcotics-terrorism nexus, Afghan drug trafficking has reinforced the power of local warlords and criminal organizations at the expense of the already weak Karzai government.

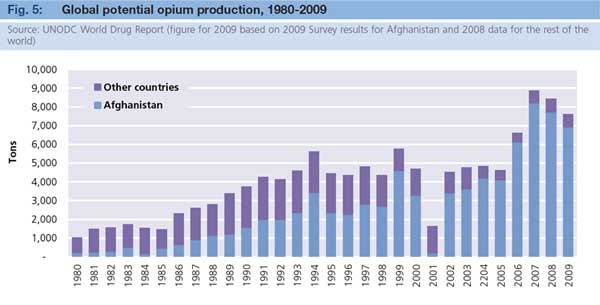

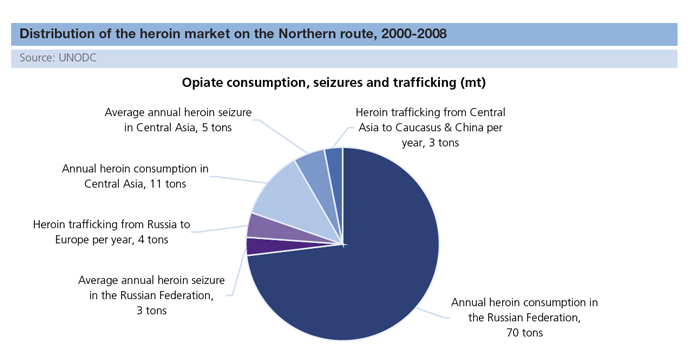

Source: Northern and Balkan Routes, World Drug Trade Report, 2010, page 22

Source: Northern and Balkan Routes, World Drug Trade Report, 2010, page 22

The Russian, Chinese, and Central Asian governments have expressed much concern about NATO’s inability to counter narcotics trafficking from Afghanistan. Russian officials estimate that some 30,000 Russians die yearly from using Afghan-based heroin—either through drug overdoses or through contracting AIDS from contaminated needles. The porous nature of the post-Soviet borders has made it easy for Afghan drug traffickers to move their product through Central Asia and northward into Russia. According to the UN, the Central Asian authorities are seizing only around 5% of the estimated 90 tons of heroin that enters their territory. While traditionally most of this flow moves on to Russia, Central Asians abuse the drugs too.

Although China does not lie along this “Northern Route,” new narcotics trafficking routes have developed from Afghanistan through Pakistan and Central Asia into China. According to the Chinese government, the narcotics smuggled into China through this conduit have more than offset the decline in imports from the Golden Triangle. The borders between Afghanistan and Pakistan are also easily crossed by the Pashtun tribesmen living on both sides of the frontier as well as others enjoy local protection. Given these conditions, the UNDOC warns:

Source: Global Heroin Flows, World Drug Report, 2010, page 45

Source: Global Heroin Flows, World Drug Report, 2010, page 45

The most sinister development yet is taking shape outside Afghanistan. Drugs are funding insurgency in Central Asia where the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Islamic Party of Turkestan, the East Turkistan Liberation Organization and other extremist groups are also profiting from the trade. The Silk Route, turned into a heroin route, is carving out a path of death and violence through one of the world’s most strategic, yet volatile regions. The perfect storm of drugs, crime and insurgency that has swirled around the Afghanistan/Pakistan border for years, is heading for Central Asia.

Insofar as the reports about competition between drug dealers precipitating the latest fighting in Kyrgyzstan are accurate, this tempest may have already have occurred.

Since NATO took over command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan in 2002, Western governments and their Afghan partners, supported by various multinational organizations, have employed a strategy involving five elements whose relative weight have varied over time: (1) conducting an effective public information campaign; (2) offering opium farmers alternative livelihood opportunities that would redirect them into legal employment activities; (3) enhancing the capacity of Afghan law enforcement agencies to prosecute major narcotraffickers through their imprisonment or extradition; (4) directly eradicating opium poppy crops; and (5) interdicting the flow of narcotics within and beyond Afghanistan.

NATO military commanders have traditionally seen their prime responsibility as combating the Taliban insurgency rather than curbing local narcotics trafficking. They have generally avoided using their scarce combat troops in direct support of the counternarcotics campaign, typically restricting their role to providing training and logistical support to Afghan security personnel in counternarcotics and counterinsurgency issues. NATO military commanders must work with local Afghan leaders to obtain intelligence and other support against the Taliban insurgents. The commanders are therefore unenthusiastic about aggressive counternarcotics activities that alienate these very leaders, who often profit from drug trafficking, as well as complicate their “hearts and mind” campaign to win over the fence-sitting population to their side.

Critics label this approach as “sequencing”—relegating a major and sustained effort to eliminate Afghan narcotics production until after the military situation had stabilized, rather than treating the drugs issue as an integral part of the region’s insurgency and terrorist problem. They believe that the overlap between the Taliban and the drug traffickers means that the counterinsurgency and counternarcotics campaigns in Afghanistan are mutually reinforcing because the military forces involved in both operations can exploit synergies by sharing resources and intelligence.

From this perspective, vigorously cracking down on the Taliban insurgents will also mitigate Afghanistan’s narcotics problem. Besides directly fighting Taliban guerrillas, NATO forces have undertaken a variety of civic action programs that could indirectly reduce drug cultivation by providing alternative sources of employment. In addition, the alliance’s efforts to strengthen the powers of the Kabul government enhance the influence of its law enforcement and other anti-narcotics agencies.

Source: Northern and Balkan Routes, World Drug Trade Report, 2010, page 54

The NATO-Afghan counternarcotics efforts are generally considered a failure. While about one-quarter of Afghan opium shipments are intercepted, only 2 percent of those interdictions occur within Afghanistan itself. The comparable interdiction rate for Colombia is about 20 percent. Seizing raw opium before it reaches heroin labs for processing is perhaps a more difficult challenge since the material is easy to store and moves through Central Asia via well-funded and entrenched trafficking networks. But much of the problem is due to the weaker state of Afghan public institutions and the widespread corruption in the country, with even high officials rumored to be involved in the drug trade. International efforts to make the Afghan counternarcotics police and the Afghan judicial system more effective have achieved minimal progress.

In addition, NATO and Afghan authorities have been trying for years to provide financial assistance to farmers for not growing the plants and instead harvest wheat, cotton, or vegetables. This strategy has had some success in reducing the overall opium production in Afghanistan’s northern provinces, but the southern provinces have made up for the lower northern yield with a spike in their own production. Particularly in the south, the lack of viable livelihoods for many Afghans has made the high profit cultivation of poppy seeds the only option for many Afghan farmers to provide for their families. Growing crops such as wheat or cotton cannot produce nearly as much profit for an Afghan farmer.

Such a disparity in potential revenue coupled with the high levels of poverty in Afghanistan has made cultivating opium a logical economic choice for farmers. While the NATO and Afghan governments have made pledges of extended funding and support for counternarcotics efforts, the amount of money that could potentially reach many farmers pales in comparison to the potential profits in illegally growing poppies.

The simultaneous resurgence of the Afghan narcotics industry and the Taliban has aggravated international tensions over how to manage the post-conflict reconstruction process in Afghanistan. Several multinational organizations and foreign countries are currently undertaking major initiatives to suppress Afghan drug trafficking. Until relative peace returns to Afghanistan or a technological fix appears, the challenge now is to integrate these diverse counternarcotics programs more comprehensively, especially by overcoming the chasm between the Western and Eurasian governments and affiliated multinational institutions, to avoid wasted resources and unnecessary frictions.

Strengthening security along the Tajik-Afghan border might provide a place to commence any joint projects since international and institutional zones of interest overlap there. Tajikistan is a member of the Moscow-dominated Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Beijing-leaning Shanghai Cooperation Organization, while NATO enjoys overflight rights over Tajikistan in support of coalition operations in Afghanistan and, like the Russian government, has been providing technical assistance to Tajikistan’s border guards and interior ministry.

Footnotes:

[1] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, World Drug Report 2010

———-

***Posted on June 29th, 2010