China’s Innovation Policies Will Create Greater Imbalances

Originally published in Manufacturing and Technology News, February 18, 2011

03/03/2011 – China’s strategy of forcing western multinational companies to transfer their most innovative technologies, research and design to China in order to continue doing business there is succeeding, and it is succeeding to the detriment of the U.S. economy, according to a recent article in the Harvard Business Review.

China’s government has been “disenchanted” by the way foreign companies have set up production of high tech goods in China and are reaping most all of the revenues and profits. A series of recent Chinese policies aimed at creating high tech state-owned competitors has stirred alarm among some multinational corporations. But the companies are more interested in staying involved in the booming Chinese market and are acquiescing to China’s demands despite the risks.

China’s requirement that companies transfer their leading edge research to China along with production is leading to an even more imbalanced trade relationship. It also is increasing the potential for conflicts between two incompatible economic systems, according to Thomas Hout, a fellow at the Center for Emerging Market Enterprise at Tufts University, and Pankaj Ghemawat from the IESE Business School in Barcelona.

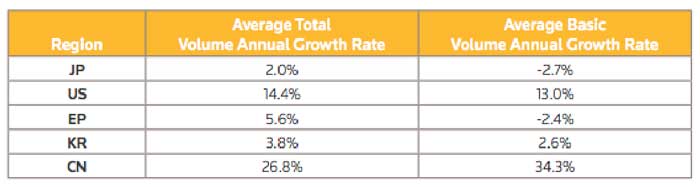

Credit: Basic Patent Trends, http://ip.thomsonreuters.com

“This is fueling tensions between Beijing and foreign governments and companies and it raises the critical issue of whether the Chinese brand of socialism can coexist with Western capitalism,” they write. “Above all, China’s strategy casts into doubt the optimistic premise that engagement and interdependence with the West would cause capitalism and socialism to converge quickly, reducing international tensions. . . This isn’t just a fight over the rules of globalization; it’s a larger issue about the inherent difficulties of connecting two big, very different economic systems.

Textbook theory suggests that imbalances trigger adjustments, but when economies are very different structurally and follow rigid policies, yoking them together will generate more imbalances — not equilibrium — and heighten tensions. CEOs eager to add another chapter to their lucrative China stories would do well to remember that the relationship between China and the West is historically unstable and to be prepared for unexpected twists and turns.”

Hout and Ghemawat note that China has already been successful at extracting technologies out of western companies, building their own internal capabilities and then excluding the companies from the Chinese market. Alstrom of France, which built the TGV high speed rail system there, Kawasaki of Japan, the builder of Japanese Bullet trains, and Siemens of Germany have all been supplanted by Chinese state owned equipment suppliers and onetime partners. The foreign firms now control little of the booming Chinese market for high speed rail equipment and systems. The same has occurred in the wind, solar and telecommunications hardware industries. China is broadening that strategy to aerospace, semiconductors and electronics. “Chinese officials have learned to tackle multinational companies, to the two authors. “Companies that resist are simply excluded from projects.”

China has already been successful at extracting technologies out of western companies, building their own internal capabilities and then excluding the companies from the Chinese market. Alstrom of France, which built the TGV high speed rail system there, Kawasaki of Japan, the builder of Japanese Bullet trains, and Siemens of Germany have all been supplanted by Chinese state owned equipment suppliers and onetime partners. The foreign firms now control little of the booming Chinese market for high speed rail equipment and systems. The same has occurred in the wind, solar and telecommunications hardware industries. China is broadening that strategy to aerospace, semiconductors and electronics.

China is able to get away with these tactics because the World Trade Organization does not crack down on them and because China has not signed international treaty provisions covering government procurement. “The WTO’s broad prohibition on technology transfers and local content requirements are more complex and easier to subvert than its rules pertaining to international trade in products,” say the two authors.

The United States needs to develop an effective response to the Chinese challenge, they add. The U.S. must overcome its “passive reliance on markets” because China will not back down.

“It might be useful for the U.S. to dispense with the premise that it can have an economically compatible relationship with China,” Hout and Ghemawat write in the article titled “Chinese vs the World: Whose Technology Is it?” “That would clarify China’s development strategy and its adverse affects on Western interests, thus heightening the lines the U.S. simply cannot allow China to cross.”