By Dr. Robbin F. Laird

04/19/2011 – The Obama Administration has come to power at a global turning point. The President has underscored the importance of working with allies and shaping a new global engagement for the United States.

At the same time, he has emphasized the need to enhance global collaboration to deal with terrorism with a global reach. And he has underscored the importance of expanding the US engagement in the global trading and economic system. He has clearly articulated the objectives of building a new role for the United States in an evolving multi-polar world.

No service is more important to this vision than the USCG. The USCG is at the vortex of commercial, law enforcement and military activities. It is tasked with a multi-mission focus in support of the protection of the homeland, securing global trade, protecting against terrorist threats at sea, interdicting the sea-borne drug trade, assuring the safety of shipping, and participating in global collaboration in securing the global commons. At the same time, with the global financial downturn, the USCG like other US agencies is to do this with constrained resources.

Yet the Administration is significantly cutting back on the USCG and its capabilities. Two cutters are to be retired from the Pacific; OMB seeks to stop the acquisition of new cutters at 4 rather than the 8 or 9 that the USCG needs; and the Maritime Patrol Aircraft numbers are to be cut significantly.

None of this makes sense unless the desire is to reduce maritime safety, security and custodianship is the strategic objective. The cost to the US economy will be significant. The Pacific fleet will not be able to provide adequate coverage for fisheries protection and this alone will guarantee the loss of billions of dollars of fishing commerce.

No area reveals a greater gap between the rhetoric of the Administration and its actions than the fate of the USCG and its missions. This gap must be closed for security, defense, and economic reasons. It is difficult to cover territory, enforce laws and provide with security with missing assets. The USCG does a great job but disappearing assets means significantly reduced safety, security and economic support to the nation.

As the Department of Homeland Security budget documents emphasizes:

The Coast Guard provides agile, adaptable, and ready operational capabilities to serve the Nation’s maritime interests. Throughout the U.S. maritime domain, the Coast Guard provides a recognized maritime presence in carrying out its safety, security, and stewardship roles. It is also the only DHS organization and Armed Service that can operate assets for both law enforcement and military purposes within and beyond U.S. territorial limits. This presence, supported by a military command, control, and communications network, gives the Coast Guard both prevention and response capabilities for all threats.

The Coast Guard can augment forces from the local level to a national or international level of involvement, regardless of the contingency. In responding to domestic disasters and emergencies, the Coast Guard can also accept and integrate assistance from DoD and other federal agencies. Moreover, the Coast Guard can flow its unique capabilities and authorities to DoD for national security contingencies. As both a military service and law-enforcement agency, the Coast Guard “straddles the seam” separating the federal government’s homeland-security and homeland-defense missions.[1]

Great statement but where is the beef?

Providing for this sort of flexibility with limited resources within a constrained budgetary environment is challenging. To do so requires shaping highly connected forces around capable multi-mission assets. Connectivity is central to effective knowledge shaping action; multi-mission assets are necessary to execute on the basis of that knowledge in a variety of different circumstances. And without the physical assets able to operate in a more effective connected environment, enhanced connectivity will not lead to effective action. An ability to cover territory with aviation assets to work with surface assets, whether ships or on-shore capabilities is central to success for the maritime security and safety team, of which the USCG is the crucial anchor.

The USCG C-130 as Seen in Elizabeth City Air Station (Credit: SLD)

The USCG C-130 as Seen in Elizabeth City Air Station (Credit: SLD)

The maritime patrol aircraft, the C-130s and the helos form together the surveillance, lift and action team, which provide significant capabilities to extend the reach of the USCG and joint surface assets. With the new platforms, which are being introduced into the USCG, the MPAs, the upgraded C-130s and networked enabled helo assets, the capability to work with the joint team is significantly enhanced.

And in an era of financial stringencies making use of joint assets, USN and US Air Force for the USCG, and vice versa is essential. The new connectivity-enabled air assets allow this to happen.

But it will not happen if you do not have the platforms; and you do not have the modern integrated systems. Enhanced connectivity is not an excuse not to buy platforms; it is the multiplier of the networked enabled new platforms being acquired.

The Connectivity Enhancer

Prior to the 9/11 attacks, the USCG had crafted a new approach to acquisition called Deepwater, which was forged upon the requirement to dramatically recapitalize ageing physical assets with limited resources. The acquisition of surface, shore and air assets were to be integrated with common C4ISR tools and approaches to provide for interoperability across the range of stakeholders in maritime safety and security.

The goal was to provide C4ISR systems, largely rooted in the use of commercial and government off-the-shelf procurement, as the backbone for an integrated service. A new central nervous system would allow for fewer, but more capable, physical assets. The events of 9/11 accelerated this approach and demanded new capabilities. Deepwater was redirected by new requirements. The USCG was tasked with handling newly defined maritime security threats. Its evolutionary approach was disrupted by the need for surge requirements to deal with new threats.

Deepwater critics have focused on problems with the acquisition of some assets – largely patrol boats and, to some extent, the new National Security Cutter. The USCG responded by shaping a new acquisition directorate to subsume Deepwater.

But lost in the shuffle has been the significant success of several shore and aviation assets as well as the core C4ISR systems and the effort to provide interoperability with its civil, commercial and military partners. The addition of a classified network, the upgrade of Inmarsat communications, the deployment of an automatic identifications system, the upgrade of law enforcement radios and other systems have greatly improved the USCG’s capabilities.

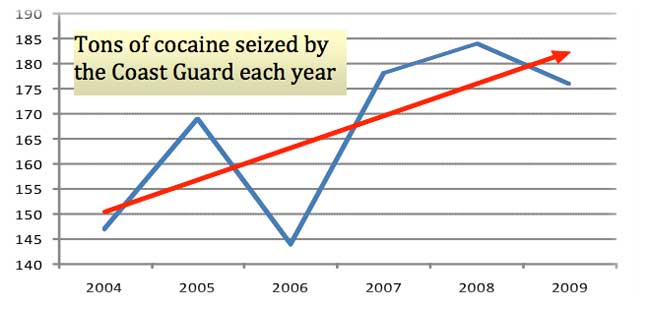

Illustrative of the impact is the role the new capabilities have played in a variety of USCG missions, including interdiction of drug trafficking. The Coast Guard combats drug trafficking in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Pacific—their work accounts for more than 50% of all cocaine seizures each year. The service also stops thousands of illegal migrants thereby avoiding billions of dollars annually in social services. At the same time, they aid persons and vessels in distress, saving lives and minimizing injuries. In addition to trained personnel, accomplishing these challenging missions requires technology—electronic charts that integrate with radar, computerized planning and tracking systems, infrared-detection gear, all weather day/night cameras and secure channel radios.

Multi-mission stations, cutters, aircraft and boats linked by communications networks permit effective operations. Electronic systems enable coordinated tactics, integrated intelligence, multi-agency interoperability and common situational awareness necessary to fulfilling statutory missions.

A good measure of success of technology implementation is the continued increase in cocaine seizures. New communications systems, coupled with the latest in electronic sensor technology, are credited with making drug trafficking intelligence rapidly available and improving target tracking, thereby achieving effective prosecution of criminal activities. These systems, deployed across multiple types of assets allow for interoperability of electronic equipment and commonality of software. Operators are able to transmit and receive classified and unclassified information to and from other assets, including surface vessels, aircraft, local law enforcement, and shore facilities. The electronic network is the glue that permits them to work together to effectively achieve a common purpose—a true force multiplier.

A common architecture deployed across multiple types of assets allows for commonality of equipment and software systems and supportability of the entire Coast Guard enterprise. In general, the Deepwater C4ISR architecture ensures an open systems approach for design and implementation, providing a web enabled infrastructure. Its architecture adapts to technology insertion and enables the progression to future Coast Guard wide C4ISR architectures.

The first National Security Cutter, USCGC BERTHOLF, has passed all TEMPEST and information assurance requirements culminating in the authority to operate. Indeed, Lockheed Martin one of the partners in Deepwater was specifically cited in a Coast Guard letter of appreciation dated Jun. 24. Delivery of the second National Security Cutter, USCGC WAESCHE, also received an excellent C4ISR evaluation and the ship was accepted with no C4ISR trial cards. Systems include electronic charts that integrate with radar, computerized planning and tracking systems, infrared-detection gear, all weather day/night cameras and secure channel radios.

Multi-Mission Platforms and the C4ISR Advantage

The Coast Guard has accepted delivery of missionized HC-130J Long Range Surveillance Maritime Patrol Aircraft. The aircraft’s new mission equipment and sensor packages are designed to deliver enhanced search, detection and tracking capabilities to perform maritime search and rescue, maritime law enforcement and homeland security missions. The aircraft modifications include installation of belly-mounted surface search radar, a nose-mounted electro-optical infrared sensor, a flight deck mission operator station and a mission integrated communication system. The mission system installed on the HC-130J is derived from the same software series developed for the mission system pallet onboard the HC-144A maritime patrol aircraft

The Coast Guard has also accepted mission system pallets for their new HC-144A “Ocean Sentry” Medium Range Surveillance Maritime Patrol Aircraft. This roll-on, roll-off suite of electronic equipment enables the aircrew to compile data from the aircraft’s multiple integrated sensors and transmit and receive both classified and unclassified information to other assets, including surface vessels, other aircraft, local law enforcement, and shore facilities.

At the heart of all these platforms is a common command and control system. It provides system interoperability as well as commonality for savings in maintenance and training. C4ISR system software reuse across Coast Guard platforms is significant. The same 100% common software between air platforms is also 41% common with the software on the National Security Cutter. The suite on the National Security Cutter leverages nearly 75% of the code from the Navy’s latest Aegis baseline while the air suite is 80% common with Navy’s P-3 Aviation Improvement Program. The command and control system is not only compatible with across the Coast Guard’s land, air and sea assets. It is also interoperable with the Navy and 117 federal agencies.

In ports and coastal areas, one of USCG’s most significant capability enhancements clearly is shaping a robust connectivity capability for the USCG and its maritime and security partners. It is a fundamental building block in improving the Coast Guard’s ability to maintain maritime domain awareness focused on meeting the needs of decision makers engaged in operations at sea, ashore, and in the air.

In spite of such developments, the Coast Guard has insufficient new assets—much of the fleet is wearing out at an ever-increasing rate. Modern communications and electronic systems are needed so that new and aging assets can be deployed effectively. And the aviation assets are not being modernized at a sufficient rate to enable to the USCG to have the reach necessary to act upon the newly acquired information generated by new C4ISR systems.

The Maritime Patrol Aircraft at the Center of the Enterprise

Too often when one thinks of a maritime service, one thinks largely of ships. Yet in a 21st century maritime enterprise, data, communications, and integrated air and surface systems are really at the heart of effective operations. The Administration is seeking within the Department of Defense to organize a more effective integration of the USAF with the USN; at the heart of this new air-sea approach is a core recognition of the role of integration of air and surface assets in mission success.

The USN has underscored the central role which it new maritime patrol aircraft and unmanned vehicles (MMA and BAMS successively) will play in maritime operations. Illustrative of this connectivity contribution by the USN’s aviation fleet was the following comment made by RADM Brooks.

The MMA will be a rapidly deployable force capable of operating independently in the far reaches of the world’s oceans or in coordination with naval, joint, or allied forces. Its superior connectivity ensures MMA a major role in FORCEnet as a key airborne node. MMA’s projected state-of-the-art communications and data links have the potential to act as sensors and provide the airborne node necessary for the Navy’s network-centric C4ISR architecture of the common undersea and common operations pictures. This capability will enable real-time, multi-channel command, control, communications, and intelligence links combined with onboard sensing, quick-look analysis, data fusing, and data dissemination to deliver timely information to naval, joint, or allied decision makers.[2]

And US forces have discovered in Iraq and Afghanistan the central role which aviation assets – manned and unmanned – can play for successful operations of ground forces. The USMC concept of the MAGTF – the combined air and ground force – is being replicated to a considerable extent as the US Army works with the US Air Force in shaping joint concepts of operations.

The USCG uses its aviation assets in a similar manner. The aviation assets – helos and MPAs – exist as an extension of the ground and surface fleet capabilities. Indeed, for the 21st century USCG much like for the 21st century US military overall, air assets extend the reach, range and capability to act of the surface assets. For the USCG this means a simple truth: a surface ship without the long reach of an MPA or a UAV cannot see very far. By extending the sight and reach of a ship or a fleet, the ability to act and to protect US equities and interests are significantly expanded.

The New MPA Provides Significant Savings in Operational Costs, a Significant Expansion in the Ability of the Fleet to Execute Missions and Carries New C4ISR Systems to Benefit the USCG, the Joint and Coalition Forces (Credit: EADS)

The New MPA Provides Significant Savings in Operational Costs, a Significant Expansion in the Ability of the Fleet to Execute Missions and Carries New C4ISR Systems to Benefit the USCG, the Joint and Coalition Forces (Credit: EADS)

With the addition of the multi-mission pallets to the MPAs, and with the ability to integrate the information gained by those systems within shipboard operations and decision making, notably with the new USCG cutter, the MPAs become especially significant extenders of fleet activity. Without this extended reach, drugs may well enter the US, illegal immigrants may well not be seen, and illegal shipping with whatever consequence may enter US waterways. Inadequate resources leads to the inability to acquire assets with clear consequences for reduced ability for the USCG to see and act on that knowledge to protect the US homeland or forces operating abroad.

The new MPA’s concept of operations is essential as well to the functioning of the 21st century USCG. The new MPAs are significant enablers for the legacy and modernized fleet. The best way to think about this is simply a simple Venn diagram in which the surface asset occupies one Venn circle, and the MPAs provide a second Venn circle significantly expanding the range of operation, and hence the ability to execute missions.

The con-ops typically depends on the mission and is essentially the same as the HC-130. Part of this calculation is the determination of proper track spacing (distance between search legs), which is a function of the size of the target (man in the water would require a very small track spacing for example), sea state, visibility, cloud cover, etc. Night searches are done if the target is thought to be capable of detection by radar, possess radio or signaling equipment. Typically a ship would be controlling one or more MPA/helicopters and continuously updating which areas have been searched and the results. Of course this function can be done by a shore station as well. The primary purpose the ship is involved at all is to be available as a helo platform and/or to launch a boarding party, engage the target if hostile or to recover survivors.

However, the C-144 can do more than just pass target position information or provide vectors. It has the ability to take photos and download them. So the ship can have information on the number of people aboard the target craft (good to know if they are bad guys) and perhaps even information on arms.

Finally fixed-wings are often required to loiter over targets or follow them until a surface can intercept. Endurance is critical here and a major shortcoming of the HU-25. The HU-25 has about 4 hours of endurance regardless of the altitude. It can fly much further high up than down low, but 4 hours is what you get. The HC-144 can provide ten hours.

The role of the MPA as a force enhancer can be seen in several examples.

The first example is the July seizure of cocaine mentioned earlier.

Late Wednesday night (July 10, 2009), the crew of the National Security Cutter Bertholf conducted the cutter’s first drug bust and disrupted a major drug smuggling operation in international waters. Two suspected drug smuggling boats, four suspected smugglers and a bale of cocaine were seized as evidence some 80 miles off the coast of Guatemala. The incident began when a group of four suspicious ‘pangas’ were spotted by a maritime patrol aircraft and alerted the Bertholf. A Coast Guard helicopter launched from the cutter and a marksman aboard was able to shoot out the engines of two speedboats and fire warning shots at the other two during the pursuit as bales were being thrown overboard from all four boats. Shortly after, Bertholf’s interceptor boats apprehended two of the boats and detained the four people onboard.[3]

The New USCG Cutter and the New MPA Provide a Significant Capability Leap and Replace Disappearing Assets (Credit: SLD)

The New USCG Cutter and the New MPA Provide a Significant Capability Leap and Replace Disappearing Assets (Credit: SLD)

The con-ops described in this operation is typical of an integrated air-to-surface operation. Obviously, all of the assets described are necessary to mission success, but the MPA as spotter and tracker is clearly at the heart of such success.

An additional example underscores the significance of the ability of the USCG through its new connectivity solutions to work with other US aviation assets to achieve mission success. Here the example is that of a 2008 drug seizure in the Pacific where a USN MPA was central to mission success.

USCG Commandant Allen wrote:

I’m proud to tell you that over the past five days, Pacific Area Coast Guard units, with the help of our U.S. Navy and interagency partners, seized over 14 tons of cocaine from two Self-Propelled Semi-Submersible (SPSS) vessels in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. On 13 September, a Navy maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) detected an SPSS in international waters and vectored a Navy ship, with a Pacific Area Law Enforcement Detachment (LEDET), to intercept it. After conducting an unannounced nighttime boarding, the LEDET discovered 7 tons of cocaine. Then on 17 September, another Navy MPA detected an SPSS and vectored the cutter MIDGETT to investigate. MIDGETT’s boarding team subsequently discovered an additional 7 tons of cocaine….The interoperability between Coast Guard and Navy assets has never been more effective.[4]

Finding a Semi-Submersible at Sea and Then Prosecuting Effectivley is a Challenging Task, Something the Drug Smugglers are Counting on for their Mission success. (Credit: USCG)

Finding a Semi-Submersible at Sea and Then Prosecuting Effectivley is a Challenging Task, Something the Drug Smugglers are Counting on for their Mission success. (Credit: USCG)

MPAs are not only central to extend the reach of surface ships but as multi-mission assets can operate alone to provide for independent actions, ranging from C4ISR missions on their own for the benefit of DHS decision-makers or as lift assets able to move goods and personnel as they did in the case of dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

With flood waters from the Mississippi River threatening several Midwestern states in June 2008, the U.S. Coast Guard put one of its newest aircraft in the air to survey the damage and to assess the condition of vital shipping lanes. The HC-144A Ocean Sentry flew over flooded portions of eastern Iowa and northeast Missouri on 19 June 2008. Though its initial operational capability was still six months off, RAdm. Joel Whitehead, Commander Coast Guard District Eight, selected the HC-144A because he believed this fixed-wing, turboprop aircraft’s longer ranges, slow flying speeds, and passenger capacity best suited the needs of the mission. Also affecting its selection over other Coast Guard aircraft was the limited availability of HU-25 Falcon jets, the aircraft the HC-144A will eventually replace.

The mission took senior Coast Guard officials, including RAdm. Whitehead and maritime industry representatives, on a flight to observe the extent of the flooding. The shipping industry representatives flew along to gain a better understanding of how the floods would impact shipping and commerce along the Mississippi River and its tributaries in Iowa and Missouri. The Ocean Sentry’s ability to fly at slower speeds allowed for more effective aerial assessment and increased time on scene.[5]

And in a crisis like the Haiti rescue effort, the lift and logistical capabilities of the USCG becomes central to the national response. Although useful to have UAVs flying over the island, better intelligence is not worth much without the lift and logistical capability of aircraft, like the USCG C-130s and MPAs.

The Challenge of Moving Forward

The legacy fleet is in extremis and the need to provide the new aircraft, which are built around significant improvements in costs of maintenance, is essential to ongoing USCG operations. The CG initially bought 41 HU-25A aircraft, of which 36 were operational. The operational fleet size was reduced in the early 1990s by Admiral Kime to fund expansion of the Marine Safety Program. The very high cost of maintaining the HU-25 (especially the engines) has been a significant burden on USCG operations. Currently the HU-25 fleet is being reduced as C-144s are brought on line. The current fleet is only 18 aircraft, 14 operational and 4 support aircraft. The CG has made minimal investment in the HU-25 over the past several years to save money. For example, the aircraft is limited to FL230 (service ceiling is FL420) because the CG elected not to invest in an upgraded IFF several years ago.

The new USCG MPA’s are the lead acquisition in the Deepwater program. The Deepwater program was built around USCG assessments of an integrated approach to executing core USCG missions. This assessment was shaped in the mid-1990s and then re-casts in the wake of post 9/11 assessments. The core approach was that an integrated C4ISR capability would allow the USCG to avoid a costly one for one replacement approach for its obsolescent assets. By integrating the replacement assets, less numbers of each particular asset would be required.

Although the execution of the Deepwater program was flawed, the underling approach remains sound. Yet the C4ISR funding for the USCG is on a downward trajectory, and the numbers of the replacement assets are going down not up. This is the worst of all possible worlds. The C4ISR, which enabled the acquisition of less numbers of platforms, is underfunded, and the result is not more platforms being acquired but less!

The only result of this will be a significant shortfall in the ability of the USCG to perform its missions, with a security shortfall and various negative consequences such as more drugs getting into the United States, more illegal immigrants with possible health hazards unnoticed, more arms trafficking from sea successfully entering the United States and so on. Failure to recapitalize the USCG is not a funding game; it is a pulling apart of the network, which protects the United States. Holes in the net are ways through for forces creating negative consequences on US territory.

In the original Deepwater schema, the USCG was projected to acquire 35 new MPAs, as well as 6 high altitude endurance organic UAVs. The UAVs were cancelled, although the USCG and DHS are looking at ways to supplement or replace the cancellation.[6] With this cancellation, organic airborne ISR was reduced and with it, the number of MPAs should logically go up by some function of the 6 cancelled UAVs, so that the number might now approach 40 MPAs.

The program is on track and on budget. The HC-144A Ocean Sentry is a derivative of the European Aeronautics and Defense Systems (EADS) CASA CN-235-300 twinturbo medium cargo/transport aircraft. It is fitted to carry sensors, search radar, and an advanced communications suite. Forming the Ocean Sentry’s nerve center is the Mission Systems Pallet (MSP) that integrates all the aircraft’s systems with a two-place operators’ station inside the cargo compartment. The MSP is a roll-on/roll-off suite of electronic equipment that allows the aircrew to compile data from the aircraft’s multiple sensors and transmit that data to other participants in the operational area.

As the USCG describes the new MPA:

This fixed-wing turbo prop aircraft provides invaluable on-scene loitering capabilities and perform various missions, including maritime patrol, law enforcement, Search and Rescue (SAR), disaster response, and cargo & personnel transport. The Mission System Pallet is a roll- on, roll-off suite of electronic equipment that enables the aircrew to compile data from the aircraft’s multiple integrated sensors and transmit and receive both classified “Secret”-level and unclassified information to other assets, including surface vessels, other aircraft, local law enforcement and shore facilities. With multiple voice and data communications capabilities, including UHF/VHF, HF, and Commercial Satellite Communications (SATCOM), the HC-144A will be able to contribute to a Common Tactical Picture (CTP) and Common Operating Picture (COP) through a networked Command and Control (C2) system that provides for data sharing via SATCOM. The aircraft is also equipped with a vessel Automatic Identification System, direction finding equipment, a surface search radar, an Electro-Optical/ Infra-Red system, and Electronic Surveillance Measures equipment to improve situational awareness and responsiveness.[7]

The new MPA is the product of a blend of several mature technologies, produced by the best defense and aerospace companies in the world. In other words, it is a mature product, in initial production with no problems to be anticipated in either continued production or ramp-up of production.

Starting with delivery in 2003, eight new MPAs have been delivered through the end of 2008 along with three mission pallets. MPAs nine through 11 are to be delivered in 2010 along with mission system pallets four through twelve. The MPA baseline fielding plan called for 16 additional MPAs to be delivered by 2014 for a total of 36.

Unfortunately, there is a reported delay in the program by senior DHS acquisition officials.[8] The proposal is to have a break in production after the deliveries in 2010. Such a delay to save near term acquisition monies will come at the expense of needed capabilities. An interruption in production will not be matched by an interruption in the threat environment facing the United States, or in the “normal” challenges facing the USCG. A funding delay is a further opening in the security net around the United States. An interruption in production is penny wise and pound-foolish.

To quote the DHS budget document:

The Coast Guard embraces a culture of response and action, with all of its personnel trained to react to “All Threats, All Hazards.” In many cases, Front-line operators are encouraged to take action commensurate with the risk scenario presented, without needing to wait for detailed direction from senior leadership. This model enables swift and effective response to a wide variety of situations.[9]

But it is difficult to provide “swift and effective response” with missing capabilities. And the absence of capabilities means simply put an enhanced probability of threats not being met today and augmented tomorrow.

[1] Budget in Brief (2010), Department of Homeland Security, pages 82-83.

[2] RADM Richard E. Brooks, USN, “The Multi-Mission Maritime Aircraft and Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Force Transformation,” Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest (Volume 24, Number 3, 2003), p. 240.

[3] The Coast Guard Compass, (July 10, 2009)

[4] http://www.eaglespeak.us/2008/09/self-propelled-semi-submersibles.html

[5] Greg Davis, “Coast Guard’s newest aircraft surveys Midwest flooding,” Naval Aviation News (January 1, 2009)

[6] Unmanned Aircraft Systems Program Update (Homeland Security, USCG, 2009).

[7] “Coast Guard Takes Delivery of First Mission Systems Pallet for its HC-144A “Ocean Sentry” Maritime Patrol Aircraft,” USCG Press Release, March 11, 2008.

[8] “Coast Guard Seeks to Avoid HC-144 Production Break,” Defense Daily (September 14, 2009).

[9] Budget in Brief, 2010 (DHS, page 83).