By Dr. Richard Weitz

06/07/2011 – The attendees of the November 19-20, 2010 NATO Lisbon summits (among the NATO heads of state alone and their subsequent meeting with President Dmitry Medvedev within the framework of the NATO-Russia Council) faced two independent BMD decisions:

(1) whether NATO would agree to integrate its missile defense programs (which focus on protecting military forces) with those being pursued until now independently by the United States in Eastern Europe (which protect aim to protect populations); and

(2) whether Russia would consider joining this effort, and to what extent (selling technologies, exchanging data, combining operations, etc). The second decision was formally independent of the first — NATO could agree to pool its efforts with those of the United States whether Russia joined this effort or not.

The main goal of U.S. officials heading into the Lisbon summit was to secure NATO’s support for linking the U.S. BMD systems that will be deployed in Europe with NATO’s collective missile defense program. In particular, the Obama administration wanted to expand NATO’s ALTBMD command-and-control system to give it the capability to support territorial missile defense in conjunction with U.S. national systems deployed near Iran.

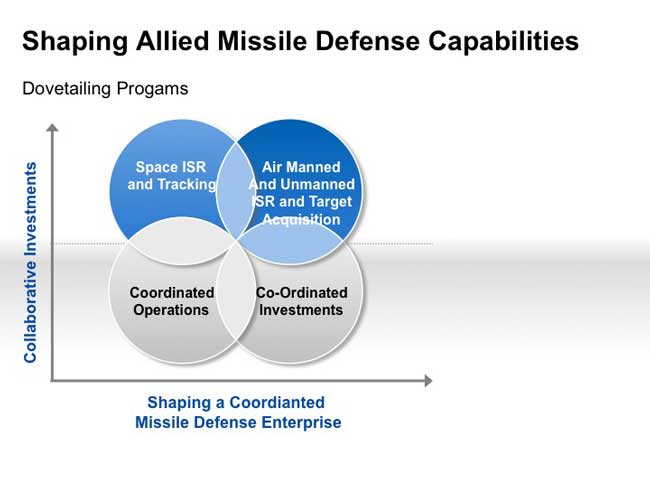

With this capacity, European countries could better integrate their BMD assets with those of the United States. For example, the U.S. SM-3 interceptor missiles are not yet accessible to European fire control systems, which operate on a different radar band. Overcoming these incompatibilities will lead to enhanced BMD protection for NATO and also help defend American military and civilian personnel in Europe. Eventually, the European-based NATO BMD assets would strengthen the U.S. ability to defend North America from long-range missile strikes.

The resulting linkage between European and American defenses would, it is hoped, reinforce the sense of common transatlantic security. For example, NATO radars could extend the sensor coverage of U.S. systems, certain Aegis-capable European warships could join with their U.S. Navy counterparts in providing joint BMD defenses of European ports, while the Patriot and other land-based missile interceptors could better network with U.S. interceptors.

As part of this newly integrated BMD architecture, the United States would like to place early-warning and tracking radars on the territory of countries near Iran, ideally to include Turkey, to be followed by increasingly effective interceptor missiles. Both the sensors and the interceptors would also be placed at sea.

Going into the Lisbon summit, the administration had already overcome several earlier objections regarding its missile defense plans. NATO leaders have come to share previously predominately American concerns about Iran’s emerging potential to launch ballistic missiles, perhaps armed with a nuclear warhead, against European targets. As the Wikileaks documents show, U.S. officials genuinely believed that Iran had received sufficient North Korean nuclear assistance to be able already to target European cities with long-range ballistic missiles.

President Medvedev at the Lisbon Summit (Credit: http://bit.ly/kqpgku)

President Medvedev at the Lisbon Summit (Credit: http://bit.ly/kqpgku)

Although Iran was not explicitly named as a focal point of NATO’s BMD systems due to Turkish sensitivities, it can be optimized to deal with an emerging Iranian missile threat.

In addition, the planned BMD architecture is sufficiently flexible that it can be adapted to deal with other possible missile threats that might emanate from the Middle East and North Africa. As designed by the Obama administration, the U.S. Phased Adaptive Approach can be adapted over tome in response to changes in NATO’s missile threat environment.

Another objection that had largely been overcome is that pursuing comprehensive missile defense would fit awkwardly with the existing alliance nuclear deterrence mission. Parrying those who argued that NATO could abandon its nuclear missions or rely more on arms control measures, U.S. officials have persuaded many allied governments that missile defense complements the alliance’s deterrence mission by causing potential aggressors to doubt that any attack could succeed as well as providing a hedge should deterrence fail. Rasmussen in particular added that the anti-ballistic missile system was a “complement” of NATO’s nuclear deterrent.

In the end, NATO missile defense advocates at the Lisbon summit successfully reinforced perceptions of a credible threat, demonstrated how NATO could leverage already acquired capabilities, stressed that burden-sharing is an imperative of any alliance, explained that enhanced European BMD capabilities will bolster European influence in missile defense decision making, revealed how BMD assets could also cope with related threats (such as those from the air or outer space), and generally persuaded NATO governments and populations that they would get good value for their money.

Nonetheless, questions persist regarding potential contradictions between missile defense and other NATO goals, the ability of the alliance to sustain the necessary expenditures for a decade to construct the system, and persistent Russian unease regarding the entire project.

At the Lisbon summit, the NATO governments agreed in principle to integrate their European missile defense programs with those of the United States, with the goal of providing comprehensive protection for NATO’s populations, territory, and forces. At Lisbon, the member governments committed to extending NATO’s Active Layered Theater Ballistic Missile Defense (ALTBMD) system to give it the capability to support territorial missile defense in conjunction with U.S. national systems deployed near Europe.

But the NATO leaders deferred resolving many of the difficult command-and-control issues regarding how to operate these new missile defense capabilities for further discussion.

And they gave their defense ministers until this June to develop a concrete action plan — which among other features would specify where to base the system — for achieving the sought-after BMD capability.

Meanwhile, NATO and Russia agreed to resume their theater missile defense exercises, which had been suspended since the 2008 Georgia War — and discuss how they could potentially cooperate on territorial missile defense in the future. Medvedev indicated Russia would consider very deep collaboration provided Moscow was treated as an equal partner, whereas the NATO governments seemed more interested in less encompassing collaboration on specific projects.

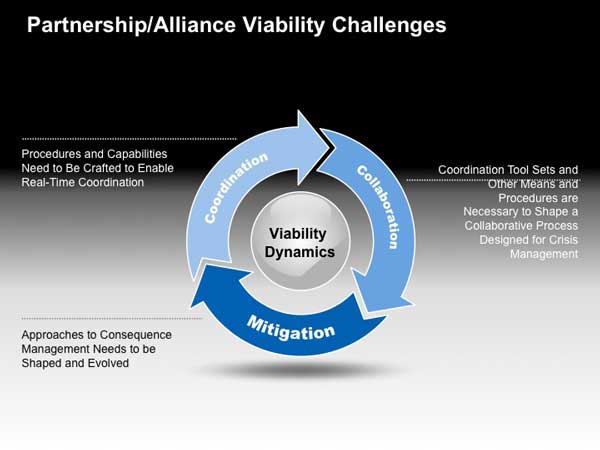

In terms of intra-NATO collaboration, unease persists about certain aspects of collective NATO missile defense. For example, to intercept a ballistic missile, a launch decision must be made in minutes. This condition could require pre-authorizing NATO commanders to attempt a missile interception without securing additional approval from civilian political leaders.

But some European officials are uneasy about allowing presumably American military leaders to take what could be an act of war (e.g., mistakenly shooting down a civilian space rocket) without requiring mandatory consultations with NATO leaders governments, especially of those allied countries from which interceptors are launched or where potentially radioactive debris might fall.

Yet, supporters of pursuing a comprehensive NATO BMD capacity note that even an erroneous launch decision is less fraught with risk than the alliance’s current nuclear mission, which has similar command-and-control arrangements to those that might be employed for NATO collective missile defense.

In addition, until they establish an integrated command-and-control system, the Europeans will be living with the U.S.-built missile defense architecture in which the United States dominates the command and control decisions.

Another long-term problem with missile defenses relates to money. Funding the upgraded ALTBMD command-and-control system extension to cover NATO’s territory and populations will require spending almost 300 million more dollars on the system than the $1.1 billion NATO already committed on the system designed to protect only NATO’s deployed military forces. Advocates consider this a bargain, especially since the United States is spending billions of dollars to deploy a range of expensive U.S. BMD systems in Europe already, but some NATO leaders genuinely believe that they cannot afford this additional expense at a time when they are implementing emergency austerity budgets to cope with the global economic slowdown.

In addition to the resulting lost tax revenue and additional counter-cyclical measures, the European governments are funding an unexpectedly costly military operation in Afghanistan and look set to adopt other new NATO commitments, such as enhanced collective cyber defenses, at the summit.

Some Europeans hope that Washington itself will eventually agree to pay entirely for the ALTBMD upgrade and other additional NATO missile defense capabilities. They see the U.S. unilaterally developing a variety of BMD systems and think that the United States might offer the allies a missile defense umbrella to complement the essentially unilateral extended nuclear deterrence guarantee Washington provides many NATO and non-NATO countries.

And some European leaders fear that U.S. and NATO analysts have underestimated the likely aggregate expenses of NATO’s acquiring and sustaining an effective comprehensive BMD capacity. For many major defense programs, substantial costs overruns occur following a procurement decision. Some European officials might be more supportive of missile defense if European companies receive many of the NATO and U.S. BMD contracts.

Many allies hope that the transatlantic missile defense will strengthen alliance cohesion and solidarity by further reinforcing the U.S. commitment to European security. Commitment is already established by the stationing of American troops and nuclear weapons, backstopped by U.S. conventional and strategic nuclear forces deployed outside Europe.

But some East European governments in particular have been concerned that the Russian-American reset is leading the United States to pay less attention to their security concerns.

Shaping a Coordinated Missile Defense Enterprise (Credit: SLD)

Shaping a Coordinated Missile Defense Enterprise (Credit: SLD)

From this perspective of strategic reassurance, the issue of the effectiveness of these systems under combat conditions is less important than the fact that, by their mere presence, they bind the allies together in another collective defense mission and symbolize continued U.S. engagement in NATO’s defense.

Ideally, this new transatlantic link would complement the existing nuclear and civilian linkages as well as NATO’s arms control and nonproliferation policies, but tensions persist between NATO’s BMD policies and the other capabilities. For example, money spent on BMD systems cannot be used to sustain conventional forces, which could exacerbate burden-sharing differences within the alliance.

How the alliance’s BMD programs link with NATO air defenses is unclear. Synergies and cost savings might be realized by using common assets for missile and air defenses. In addition, some threats, such as long-range cruise missiles, might fall between them if kept too separate.

Whereas some in NATO – including some Germans – see missile defense as a substitute from more aggressive threats to retaliate to attack with nuclear weapons, others see them as possibly encouraging a nuclear first strike by leading an actor to think they might be able to destroy so many of the target state’s own nuclear weapons and supporting command and control facilities that they could then use missile defenses to blunt any nuclear response.

Finally, whereas some NATO leaders argue that missile defenses will improve NATO-Russian relations through a cooperative work program, other allies continue to worry that pursuing comprehensive missile defenses will antagonize Russia.

At the Summit, NATO and Russia agreed to cooperate more on BMD issues. For example, they have committed to resuming their theater missile defense exercises, which had been suspended since the 2008 Georgia War — and discuss how they could potentially cooperate on territorial missile defense in the future.

NATO and Russian experts are now addressing such questions as what a common architecture could look like, what costs and technologies might be shared between NATO and Russia, how the knowledge gained from the joint exercises might be applied to a standing joint BMD system, and how NATO and Russia might cooperate to defend European territory as well as NATO and Russian military forces on deployment.

Yet, Medvedev indicated Russia would consider very deep collaboration provided Moscow was treated as an equal partner. He had proposed that NATO and Russia establish a joint sectoral missile defense architecture for Europe in which each party would be in charge of defending the other from missiles the fly through its territory.

Medvedev and other Russian officials warn of a new Cold War style arms race if Russia and NATO cannot agree on a cooperative European missile defense program. They have presented the choice as between full Russian participation in any NATO missile defense system (which is politically and technically impossible) or renewed confrontation (which is undesirable, unnecessary, and unwarranted).

For a comprehensive look at how to build a real trans-Atlantic capability in this area see this insightful analysis and as well as another analysis by Ambassador Jon Glassman.