07/11/2011 – The recent successful launch of Russia’s RSM-56 Bulava (NATO code name SS-NX-30) Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) may finally mark a turning point for this troubled weapons system.

On June 28, a Bulava left a submerged next-generation Borey-class submarine, the Yuri Dolgoruky, and flew 6,000 kilometers from the White Sea to the Kura test range in Russia’s Far East Kamchatka region. Three days later, Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov announced that the Bulava will enter into serial production next year. Russian military sources indicated that they would conduct four additional tests of the missile before placing the Bulava into service by the end of 2011.

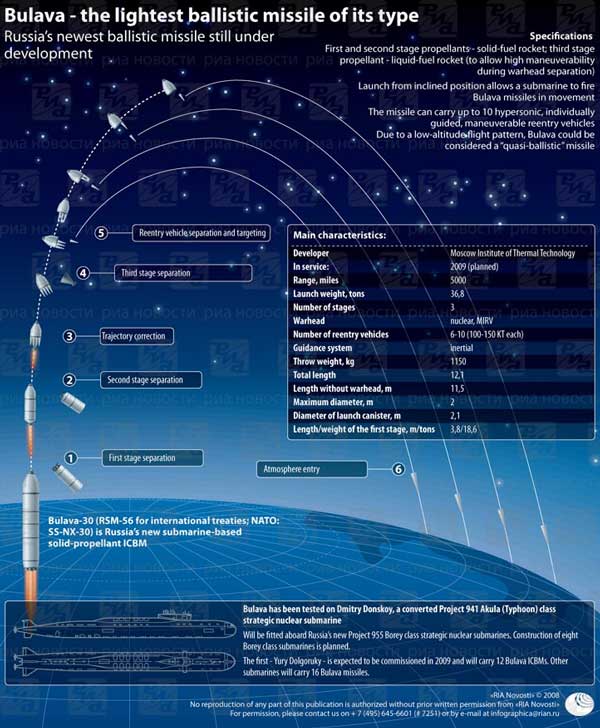

The Bulava (Russian: Булава; “mace” in English) is designed to carry 10 maneuverable and independently targeted (MIRVed) nuclear warheads, with a destructive power of some 100-150 kilotons each, a maximum range of some 8,000 kilometers. On paper, the Bulava’s advanced missile defense countermeasures, solid-fuel propellant, small size, light weight, rapid speed, maneuverability, and other capabilities make it a superior deterrent to anything in Russia’s existing SLBM arsenal.

(Credit: http://defenddeterrence.com/news/?p=695)

(Credit: http://defenddeterrence.com/news/?p=695)

Unfortunately, the Bulava’s terrible test record has resulted in its remaining a paper system for years beyond 2006, its originally scheduled date for entering into service. More than half of the missile’s 15 test launches failed, sometimes spectacularly.

The repeated failures of the Bulava test flights proved an embarrassment for the Russian defense industry at a time when the Russian government was trying to reestablish Moscow’s claims to great power status.

The Bulava represents one of the few major Russian weapons systems developed after the Soviet Union’s collapse. It is probably also the most expensive military research and development program in Russian history. One experienced Russian analyst estimates that the Bulava, combined with the new Borey-class submarine to launch it, recently consumed 40% of Russia’s defense budget.

The Baluva’s problems result from two primary factors. The first is the mistaken if understandable Russian government decision to award the original contract to the wrong design firm and then follows its bad advice. The second was more serious mistake of continuing weaknesses in Russia’s military-industrial complex, especially production, quality control, and systems integration problems.

In 1998, the Russian Security Council awarded a development contract for a new SLBM to the Moscow Institute of Thermal Technology (MITT), led by the well-respected missile-designer, Yuri Solomonov, after the government had abandoned its program to develop an earlier SLBM, the SS-NX-28 (D-19M) Bark. The Bark, designed by the rival Makeyev Design Bureau, had experienced three successive failures during test launches and its development costs were soaring.

Yet, while the MITT had earlier developed the successful ground-based RT-2PM Topol (SS-25 Sickle) and the RT-2PMU Topol-M (SS-27) land-based ICBMs, it had never built a SLBM. Solomonov argued that his team could save considerable time and money (both in short supply because of the Bark debacle) by incorporating many of the innovative features already developed for the Topol-M into the Bulava program.

The most important innovations were the missile’s ability to accelerate rapidly soon after launch, a capacity designed to overcome any U.S. post-boost phase missile defenses.

The Russian government heeded Solomonov’s advice regarding the Bulava. Russia’s budgetary woes in the 1990s caused policymakers to try to save money by standardizing the research and development of the production of ballistic missiles, regardless of whether they were land-based or launched at sea.

The design of this three-staged SLBM is similar though not identical to the Topol-M. Russian officials also followed Solomonov’s recommendation to proceed rapidly to sea-based trials rather than conduct extensive initial land-based testing. Such “ground testing”—especially sophisticated computer-aided modeling of a missile or other aerospace vehicle that could locate potential flaws before conducting an expensive and, if failed, embarrassing test flight—is standard procedure for American and European missile design firms, but is rarer in Russia due to the lack of modern infrastructure and funding.

The intent was to accelerate the Bulava’s deployment and minimize its development costs, which had begun to exceed the initial budget. These government decisions and development shortcuts may have contributed to the missile’s recent problems.

Besides the overly ambitious design schedule, problems of production, quality control, and systems integration—coordinating the input of the dozens of independent subcontractors involved—was as a major reason for the Bulava’s difficulties. The large number of failures was due to a variety of problems rather than a single cause, making it difficult for the designers to correct the problem. Some failures affected the first stage, others occurred later in flight, while some difficulties arose even before launch. It looks as if different subcontractors provided defective equipment or material or inadequate service for many of the tests, meaning that correcting the defect from the previous launch did not prevent different problems from arising the next trial launch.

Furthermore, the Votkinsk Plant State Production Association where the missile was assembled and manufactured was also experiencing poor industrial production standards, quality control, and obsolete equipment. A factory manager at the Votkinsk plant stated on average 83% of the equipment was worn out and that 50 billion rubles were needed through 2020 for modernizing the factory’s equipment. Votkinsk also suffered from a lack of young specialists to replace the experienced staff who was retiring without mentoring a team of successors.

More generally, the design of the Bulava has to be compromised because the decline in Russia’s military-industrial base meant that many desired parts were no longer available. Vladimir Vysostsky, a senior Russian Navy official, officially explained Bulava’s issues as the consequence of a “deep, elementary dysfunction in the technical industry for… strategic missiles.” C.H. Kovalyova, the creator of the Akula submarine, has said that a lack of certain necessary support structures is contributed to Bulava’s mishaps.

Successive failures due to a variety of problems led an increasing number of Russian defense analysts and officials to consider abandoning the project despite the 100 billion rubles already spent on the system.

Nonetheless, the Russian government felt it had to persist with the Bulava because the weapon has been designed to work with Russia’s next-generation Borey-class (Project 955) ballistic missile launching submarine (SSBN). Since 1996, the nuclear-powered Borey has been the only strategic submarine under production in Russia. The Russian Navy has been waiting impatiently for these boats since the existing fleet of Delta and Typhoon SSBNs are exhausting their service lives as they undertake their so-called “deterrence cruises” through the Arctic and Pacific Oceans.

One Project 941 Akula-class Typhoon, the Dmitriy Donskoy, has been serving as a specially modified test platform for most of the Bulava launches pending completion of the first Borey-class ship. The first Borey-class SSBN, the Yury Dolgoruky, has begun sea trials and conducted the successful June 28 launch. The second, the Alexander Nevsky, is at the final stages of construction at the Sevmash Machine Building Enterprise shipyard in northern Russia. The Russian Ministry of Defense plans to build at least six additional Borey ships, with the third and fourth also already under construction at Sevmash. Although the Yuri Dolgoruky is designed to carry as many as 12 Bulava SLBMs, the next three Borey ships will have 16 launch tubes able to accommodate the Bulava missile.

The Russian military is considering designing the remaining four Borey SSBNs to launch as many as 20 Bulavas. The Russian government plans to manufacture at least 150 Bulava SLBMs. The Russian military intends the Borey-Bulava combination to serve as the foundation of Russia’s nuclear triad until 2040. If the Bulava does not work, these billion-dollar Boreys will have nothing to fire.

The most popular alternative proposal was to retrofit the Borey to carry the R-29RM Sineva-class ballistic missile, another recently developed Russian SLBM. Although not as advanced as Bulava (the Sineva uses liquid rather than solid fuel and lacks some of Bulava’s defensive capabilities), Sineva is a capable modern missile that has an impressive launch record.

(Credit: http://warfare.ru/?linkid=1715&catid=265)

(Credit: http://warfare.ru/?linkid=1715&catid=265)

Yet, fitting the Borei to carry Sineva missiles would be expensive and time-consuming. Although Russian government and academic experts supporting the government’s general military reform program argue that their country faces no immediate military threat and therefore has time to undertake a comprehensive if challenging defense restructuring, the Russian military has steadfastly rejected the Sineva option or other alternatives.

Russian defense managers may have recalled Soviet experience when, in some cases, Russian weapons that had a long and tortuous development process ended up working well despite their early struggles. The R39 (SS-N-20 “Sturgeon”) was a Soviet SLBM project which began development in 1971, failed more than half its initial test flights, and was stuck in development for 12 years. Nevertheless, its problems were eventually worked out and the R39 served well in the Soviet and Russian Navy until 2004. The fact that the Bulava introduces path-breaking technologies into Russia’s SLBM force made that country’s defense managers expect that there would be many initial test failures. As Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev wrote in July 2009: “Bulava is a new rocket; in the course of its development we will encounter various setbacks… nothing new happens quickly.”

Another theoretical option would be for Russia to get out of the nuclear weapons business entirely. Yet, eliminating nuclear weapons enjoys little support among the Russian national security elite, who see Russia’s nuclear weapons as their ultimate instrument of defense, deterrence, and global influence.

Shortly after NATO commenced bombing Libya, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin made a special trip to the Votkinsk factory where the Bulava is produced. Putin used the occasion to remind its workers that Russia’s nuclear weapons shielded their country against a similar attack by Western powers. In his words, “they bombed Belgrade, Bush started a war in Afghanistan, then under a pretext, an entirely lying pretext, started a war in Iraq, liquidated the whole Iraqi leadership, now they’ve started to bomb Libya… today’s situation once again confirms the correctness of what we are doing to strengthen the defense capabilities of our country, and the new program of governmental arms-building is intended to achieve this.”

Although Russian designers may finally have gotten the Borey-Bulava combination to work, this success may prove exceptional. The Russian government devoted enormous sums to this one very important project, and cannot undertake a comparable effort with all its desired military systems. This limitation partly explains why Serdykov had to deny recent media reports that the Russian government planned to build an aircraft carrier in the next decade.

It also explains why Russian leaders are willing to buy expensive foreign weapons systems like the Mistral-class amphibious assault ship. Russian defense companies, having not yet recovered from the traumatic breakup of the Soviet-era military-industrial complex, are still incapable of building such a complex weapons system in a timely manner.