By Dr. Robbin Laird

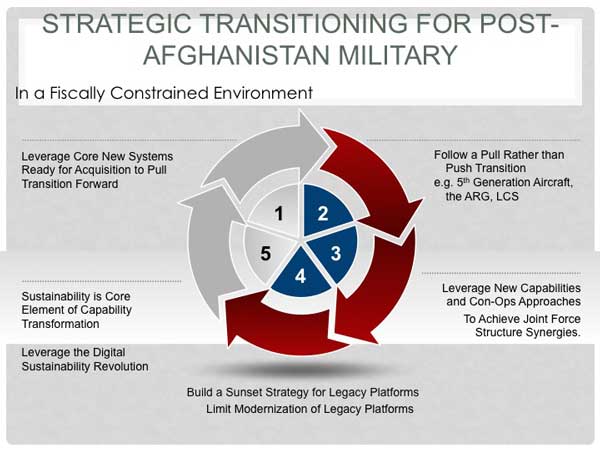

09/26/2011 – The United States is facing twin pressures of fiscal constraints and a drawdown and withdrawal from Afghanistan. The first highlights the need to reduce budgets; the second focuses upon the re-configuration of US forces.

The need to reduce budgets in the context of a significant drawdown can be met in significant part by removing the two billion dollar a week cost to operate in Afghanistan. The logistics costs in Afghanistan alone have diverted money from investment accounts and have frozen US forces into a force in being to manage territory. Cost savings from withdrawal need to be conjoined with a significant re-configuration of forces as withdrawal unfolds. Indeed, one could argue that the withdrawal and the re-configuration of Big Army are closely connected. Indeed if Secretary Panetta can manage it, the withdrawal, downsizing and reconfiguration of Big Army is really at the heart of structural redesign of US forces.

US forces need to become more agile, flexible, and global in order to work with allies and partners to deal with evolving global realities. Protecting access points, the global conveyer of goods and services, ensuring an ability to work with global partners in having access to commodities, shaping insertion forces which can pursue terrorist elements wherever necessary, and partnering support with global players all require a re-enforced maritime and air capability. This means a priority for the USCG, USN, USMC and the US Air Force in the re-configuring effort. Balanced force structure reduction makes no sense because the force structure was re-designed for land wars that the US will not engage in the decade ahead. The US Army can be recast by the overall effort to shape new power projection capabilities and competencies in the decade ahead.

Retiring older USN, USMC, and USAF systems, which are logistical money hogs and high maintenance, can shape affordability. Core new systems can be leveraged to shape a pull rather than a push transition strategy. Fortunately, the country is already building these new systems and is in a position to shape an effective transition to a more affordable power projection capability.

At the heart of the approach is to move from the platform-centric focus where the cost of a new product is considered the debate point; rather the value of new systems and their ability to be conjoined is the focal point. No platform fights alone is the mantra; and core recognition of how the new platforms work with one another to shape collaborative con-ops and capabilities is central to a strategic re-design of US forces.

A good illustration of this approach can be seen with regard to crafting 21st century air capabilities. 21st century air capabilities are built around the three “M”s. The aircraft need to be multi-mission and manufactured to be significantly more maintainable than 20th century aircraft.

In today’s world, the acquisition of aircraft in financially stringent environments favors multi-mission platforms. The U.S. and allied air forces are buying less aircraft and a smaller variety of aircraft. The expectation is that the aircraft purchased will do more than their core specialty.

There is an expectation that if I buy an airlifter it will do more than airlift. It will be able to refuel, it will be able to deliver in the air lethal and non-lethal weapons out of the back of the aircraft, it will be able to become a C2 aircraft if needed, etc.

The second M is maintainability. New platforms are built with a significant amount of attention to how to enhance their ability to be maintained over time. When platforms were built thirty years ago, logistics support was an afterthought. No it is a core element of determining successful outcomes to the manufacturing process.

Sustainability is a core requirement for 21st century air forces and air operations. Sustainability is a combination of logistics and maintainability considerations combined. Designing a more sustainable product, which can operate fleet wide, should be one of the very core procurement principles.

But it does not even exist on the playing field. The questionable notion of life-cycle costs is used but has little or nor real meaning as key drivers of life cycle costs are often outside of the domain of a platform considered by itself or fleet wide.

Additionally, one needs to buy Fleetwide. Savings will come from pooling resources, something that cannot happen if you buy a gaggle of aircraft, rather than operating a common fleet. Just ask Fed Ex what commonality for their fleet delivers in terms of performance and savings.

The final M is manufacturability. Briefing slides and simulations are not the same thing as a finished good of high quality and of high reliability. Here you need a trained workforce, good engineering practices and an ability to deliver a product of high quality and standards. It is challenging to build new systems and not every manufacturer is created equal.

A core element of today’s manufacturing systems is the challenge of managing extended supply chains. And these supply chains are subject to disruptions and the need to manage those disruptions.

An excellent example of how to leverage what you are buying for the evolution of overall maritime security and defense capabilities are the intersections between the USCG’s National Security Cutter, the USMC’s F-35B and the Osprey.

Shaping a collaborative approach for these systems via the aviation assets and C4ISR systems is suggestive of a leveraging strategy.

The National Security Cutter is already deployed in the Pacific and provides a significant enduring presence in the Pacific. Any US strategy for the Pacific – which is clearly one of the key definitional areas for the next decades for US strategy – needs to operate from the Arctic to Australia. And here the USCG’s core endurance asset is a key player. The ship is currently being bought on a fixed priced contract, but the Congress is certainly not rewarding the Service for good behavior, but in any case the USCG needs more than 8 NSCs with 3-4 available in the Pacific.

As Admiral Currier, the Deputy Commandant (Mission Support) of the USCG, recently noted:

The National Security Cutter, in addition to being able to operate at high sea states, can launch and recover aircraft under those conditions. You have to understand the cutter’s utility as a weapon system.

It’s a platform for multiple, fast, small interceptor boats, surface craft, and also air assets, whether it be a helicopter, or unmanned aerial vehicle, which really extends the reach of the cutter significantly. We have a larger capacity for the small, fast boats, the interceptor boats. We can carry three vice one or two on a 378. The NSC is a sea base for fast response small boats and helicopters or virtually any specialized force for dealing with a wide spectrum of threats.

We’ve proven this concept repeatedly with interdiction of narcotic go-fasts in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific. With a Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), or with the use of non-USCG national assets, the ship is able to detect, monitor, and be in position to launch its helicopters, which will stop the suspect vessel, followed by the small boat boarding team.

It is a complete package. It capitalizes on external cues, intelligence, and airborne maritime patrols to develop a picture of the area. With the available maritime domain awareness, it can prosecute threats using its fast, armed, small boats, and its armed helicopters.

This asset provides an enduring presence asset globally, which can work with other USN, USMC or USAF assets in delivering global security solutions essential to 21st century operations.

And the NSC can fit into the puzzle of managing security and defense threats along with the other new assets being shaped by the USMC and the USN. The USMC intends to deploy the F-35B and the Osprey on its Amphibious Ready Group and these new assets significantly change the capabilities of the ARG and the ability of the ARG to work with other USN and USCG and USAF assets.

Yet the F-35B “debate” focuses on the IOC cost of the plane, not the value it brings to maritime transformation and the enablement of the joint force. The F-35B brings electronic warfare and cyber operations capability to the ARG; it provides C4ISR to command aviation and maritime assets; and it can redeploy to austere airfields to support ground operations across the spectrum of security and defense operations. And oh by the way can get places fast with its supersonic capabilities.

And coupled with the Osprey, which has only barely begun to be fully connected to a networked force, a newly enabled ARG is emerging. As General “Dog” Davis, currently the Commander of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing at Cherry Point, North Carolina, has argued:

Our MEUs have never been used as effectively as they are today. These new capabilities are going to make them exponentially more potent and useful to our nation’s leadership.

The F-35Bs give the new ARG a very high-end air superiority fighter, that’s low observable if I want it to be. I can roll from Air to Air to Air to Ground quickly and be superior to all comers in both missions. That’s bad news for our adversaries. I can use the F-35s to escort the V-22s deep into enemy territory. With those V-22s we can range out to a 400-500-mile radius from the ship without air refueling. I can go deliver Marines deep in the enemy territory or wherever and do it at 250 miles an hour, so my speed of action, my agility is exponentially increased, and I think if you’re a bad guy, that would probably give you a reason to pause. It’s a very different animal that’s out there. We are good now, but will be even more so (by more than a factor of two in the future).

I also have significant mix and match capability. And this capability can change the impact of the ARG on the evolving situation. It is a forcing function enabled by variant mixes of capability. If I wanted to strip some V-22s off the deck, to accommodate more F-35s – I could do so easily. Their long legs allow them to lily pad for a limited period of time — off a much large array of shore FOBs – while still supporting the MEU. It’s much easier to do that in a V-22 than it is a traditional helicopter.

I open up that flight deck, or I can TRANSLANT or PAC additional F-35s. If I had six on the deck and I want to fly over another six or another four, we could do it rather quickly. Now the MEU has ten strike platforms. So if I need to have a TACAIR surge for a period of time, that deck provides a great platform for us. We’ve got the maintenance onboard that ship, so we can actually turn that Amphib very quickly from being a heliocentric Amphib to a fast jet Amphib. Conversely, I could also take the F-35s off, send them to a FOB and load it up with V-22s, 53Ks, or AH-1Zs and UH-1Ys. Flexible machines and flexible ships. The combination is exceptional.

We will have a very configurable, agile ship to reconfigure almost on a dime based on the situation at hand. I think the enemy would look at the ARG as something completely different from what we have now. I think we have to change the way we do things a bit in order to allow for that, but I think we will once we get the new air assets. The newly enabled ARG, or newly whichever the term you’re using, will force our opponents to look at things very differently. We will use it differently, and our opponents are going to look at it differently.

And of course, the USMC helos can land on the NSCs and support the higher end operations and needs for the NSCs as DoD assets. And narco and terrorist elements are using higher end capabilities such as mini-subs and fast planes, for which an overlap in ARG and NSC operations can provide a potent mix.

Now let us add the new Littoral Combat Ship to the mix. Again, no platform fights alone and in the new fiscally constrained environment driving maximum values from any new platform purchase is a sound idea. And as one builds collaborative con-ops across the joint force, a more effective power projection force can be shaped.

These two forces – the LCS and the newly configured ARG – can be conjoined and forged into an enlarged littoral combat capability. But without the newly configured ARG, and the core asset, the F-35B, such potential is undercut.

This is a good example of how buying the right platform – the F-35B – is part of a leveraging strategy whereby greater value is provided for the fleet through the acquisition of that platform.

In a time of fiscal stringency, good value acquisitions need to be prioritized. Such acquisitions are able to leverage already acquired or in the process of being acquired capabilities and provide significant enhancement of capabilities.

They are high value assets, both in terms of warfighting and best value from an overall fleet perspective.

The USN-USMC amphibious team can provide for a wide-range of options for the President simply by being offshore, with 5th generation aircraft capability on board which provides 360 situational awareness, deep visibility over the air and ground space, and carrying significant capability on board to empower a full spectrum force as needed.

Now add the LCS. The LCS provides a tip of the spear, presence mission capability. The speed of the ship allows it to provide forward presence more rapidly than any other ship in the USN-USMC inventory.

It was said in fighter aviation “speed is life” and in certain situations the LCS can be paid the same complement. The key is not only the ships agility and speed but it can carry helicopters and arrive on station with state-of-the art C4ISR capabilities to meld into the F-35B combat umbrella. Visualize a 40+ knot Iron Dome asset linking to Aegis ships and the ARG air assets.

By shaping a pull rather than push transition strategy, these new platforms WHICH ARE ALREADY BEING bought can provide for new capabilities by shaping collaborative con-ops. Significant savings come after having made the transition for older less fuel efficient and environmentally unfriendly 40-50 platforms, which suck up sustainment dollars.

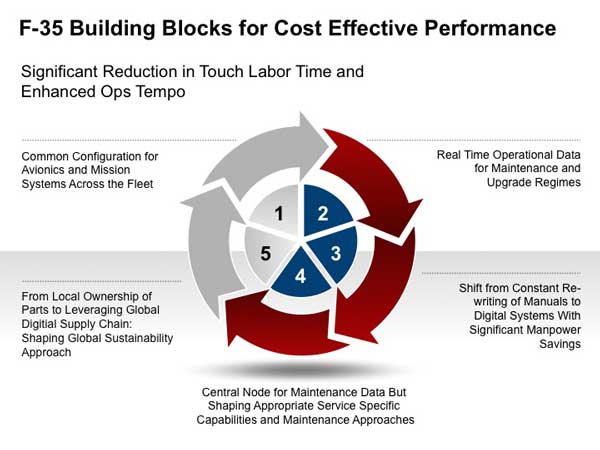

To provide simply one example would be the impact of the F-35 on logs bills. Shifting from the legacy air fleet to the F-35 fleet will save trillions of dollars in operational support. Although the headlines were generated on the more than 1 trillion support costs of the F-35 fleet in 2065 dollars, what was missed that the legacy fleet in those very 2065 dollars would cost more than 4 trillion dollars.

The plane has been designed to optimize maintainability and to reduce the amount of touch labor on the plane by at least 30%. And the fleet commonality will lead to significant ability to operate, deploy and sustain fleets of aircraft.

Recently, retired head of Marine Corps Aviation General Trautman hammered the first point home.

Affordability is the balance of cost and capabilities required to accomplish assigned missions. For over a decade the Marine Corps has avoided the cost of new procurement during a time when the service lives of our legacy aircraft were sufficient to meet the missions assigned. However, in the near future, our investment in the capabilities of the F-35B will outweigh the unavoidable legacy aircraft operations and sustainment (O&S) cost increases we will incur with the F/A-18, AV-8B, and EA-6B.

The O&S costs of legacy aircraft across DoD have been increasing at an average rate of 7.8% per year since 2000. The operational lifetimes of legacy aircraft are being extended well beyond their original design limits. As a result, we have been continually engaged in a struggle to maintain operational readiness of our legacy aircraft due largely to the increasing age of the aircraft fleet. Early in an aircraft’s life cycle, the principal challenge is primarily attributed to the aging proprietary avionics systems upon which the user depends for warfighting relevance; later it is maintenance of the airframe and hardware components that are become the O&S cost drivers.

The Marine Corps strategy for the last eleven years has been to forego the procurement new variants of legacy aircraft and continuing a process of trying to sustain old designs that inherit the obsolescence and fatigue life issues of their predecessors. Instead, we opted to transition to a new 5th generation aircraft that takes advantage of technology improvements, which generate substantial savings in ownership cost. The capabilities of the F-35B enable the Marine Corps to replace three legacy aircraft types and retain the capability of executing all our missions.

This results in tangible O&S cost savings.

A common platform produces a common support and sustainment base. By necking down to one type of aircraft we eliminate a threefold redundancy in manpower, operating materiel, support services, training, maintenance competencies, technical systems management, tools, and aircraft upgrades. For example:

Direct military manpower will be reduced by 30%; approximately 340 officers and 2600 enlisted.

- Within the Naval Aviation Enterprise we will reduce the technical management requirements the systems requiring support by 60%.

- Peculiar Support Equipment will be reduced by 60%; down from 1,400 to 400 line items.

- Simulators and training support systems will be reduced by 80%; five different training systems will neck down to one.

- Electronic Attack WRA’s will be reduced by 40% and replaced with easier to support state of the art digital electronics.

- The Performance Based Logistics construct will nearly eliminate macro and micro avionics repair, and intermediate propulsion support functions.

- Airborne Armament Equipment (AAE) will be reduced by over 80% with the incorporation of a multi-use bomb rack.

Compared to historical parametrics we expect our overall O&S costs to decrease by 30%.

The key to enabling these reductions is to evolve our supportability concepts, processes and procedures instead of shackling ourselves to a support infrastructure built for legacy aircraft. We need to be innovative and ensure our sustainment posture keeps pace with technology advancements and global partnering synergies. Working together with industry, the Marine Corps is intently focused on the future as we seek innovative cost effective sustainment strategies that match the game changing operational capabilities resident in the F-35 Lightning II.

The impact of fleet operations was highlighted by retired General Cameron, now working on the F-35 program with Lockheed Martin. Cameron as a retired USAF general in charge of maintenance highlighted the fleet consequences of shifting form F-16s to F-35As for the USAF.

The real beauty of the F-35 program is the fact that you can look out across the entire fleet, all the international partners, all the domestic partners, and tell immediately if there are systemic fleet wide issues. The program can share assets to ensure a surge capability to wherever it’s needed and can share the robust supply chain that’s already established on the F-35 production line. Our experiences with the F-16 highlight another major advantage of the F-35 approach. The F-16 has been a highly successful program. However, configuration management has been a challenge because it has been handled at the individual service level. Therefore, there are roughly 130 configurations of the F-16. The operators, when prosecuting the air battle, have to know the precise configuration of each F-16 in order to know what capabilities it brings to the fight. The sustainment of the F-16 is even more challenging with spares not being interchangeable among F-16 variants. The F-35 is a common configuration so interoperability is the key in both operations and sustainment.

One could simply note that the views of such warfighters are simply bypassed in making wild assumptions about future life-cycle costs. An alternative approach would be to examine how the F-35 as manufactured leads to significant REDUCTIONS in touch labor time and to ENHANCED operational tempo, which in turn lead to COMBINED reduction in maintenance costs with enhanced, combat efficiencies.

In conclusion, the combining of the withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq, the sizing down of Big Army, and leveraging the new platforms already being built, the retirement of older platforms and systems can together form an acquisition strategy to shape the new US power projection capabilities for the 21st century. If one simply downsizes a skewed force structure of the last 10 years, an historic opportunity would be missed.

First published in Common Defense Quarterly, Fall 2011

By Dr. Robbin Laird

09/19/2011 – The United States is facing twin pressures of fiscal constraints and a drawdown and withdrawal from Afghanistan.The first highlights the need to reduce budgets; the second focuses upon the re-configuration of US forces.

The need to reduce budgets in the context of a significant drawdown can be met in significant part by removing the two billion dollar a week cost to operate in Afghanistan. The logistics costs in Afghanistan alone have diverted money from investment accounts and have frozen US forces into a force in being to manage territory. Cost savings from withdrawal need to be conjoined with a significant re-configuration of forces as withdrawal unfolds. Indeed, one could argue that the withdrawal and the re-configuration of Big Army are closely connected. Indeed if Secretary Panetta can manage it, the withdrawal, downsizing and reconfiguration of Big Army is really at the heart of structural redesign of US forces. strategic

US forces need to become more agile, flexible, and global in order to work with allies and partners to deal with evolving global realities. Protecting access points, the global conveyer of goods and services, ensuring an ability to work with global partners in having access to commodities, shaping insertion forces which can pursue terrorist elements wherever necessary, and partnering support with global players all require a re-enforced maritime and air capability. This means a priority for the USCG, USN, USMC and the US Air Force in the re-configuring effort. Balanced force structure reduction makes no sense because the force structure was re-designed for land wars that the US will not engage in the decade ahead. The US Army can be recast by the overall effort to shape new power projection capabilities and competencies in the decade ahead.

Retiring older USN, USMC, and USAF systems, which are logistical money hogs and high maintenance, can shape affordability. Core new systems can be leveraged to shape a pull rather than a push transition strategy. Fortunately, the country is already building these new systems and is in a position to shape an effective transition to a more affordable power projection capability.

At the heart of the approach is to move from the platform-centric focus where the cost of a new product is considered the debate point; rather the value of new systems and their ability to be conjoined is the focal point. No platform fights alone is the mantra; and core recognition of how the new platforms work with one another to shape collaborative con-ops and capabilities is central to a strategic re-design of US forces.

A good illustration of this approach can be seen with regard to crafting 21st century air capabilities. 21st century air capabilities are built around the three “M”s. The aircraft need to be multi-mission and manufactured to be significantly more maintainable than 20th century aircraft.

In today’s world, the acquisition of aircraft in financially stringent environments favors multi-mission platforms. The U.S. and allied air forces are buying less aircraft and a smaller variety of aircraft. The expectation is that the aircraft purchased will do more than their core specialty.

There is an expectation that if I buy an airlifter it will do more than airlift. It will be able to refuel, it will be able to deliver in the air lethal and non-lethal weapons out of the back of the aircraft, it will be able to become a C2 aircraft if needed, etc.

The second M is maintainability. New platforms are built with a significant amount of attention to how to enhance their ability to be maintained over time. When platforms were built thirty years ago, logistics support was an afterthought. No it is a core element of determining successful outcomes to the manufacturing process.

Sustainability is a core requirement for 21st century air forces and air operations. Sustainability is a combination of logistics and maintainability considerations combined. Designing a more sustainable product, which can operate fleet wide, should be one of the very core procurement principles.

But it does not even exist on the playing field. The questionable notion of life-cycle costs is used but has little or nor real meaning as key drivers of life cycle costs are often outside of the domain of a platform considered by itself or fleet wide.

Additionally, one needs to buy Fleetwide. Savings will come from pooling resources, something that cannot happen if you buy a gaggle of aircraft, rather than operating a common fleet. Just ask Fed Ex what commonality for their fleet delivers in terms of performance and savings.

The final M is manufacturability. Briefing slides and simulations are not the same thing as a finished good of high quality and of high reliability. Here you need a trained workforce, good engineering practices and an ability to deliver a product of high quality and standards. It is challenging to build new systems and not every manufacturer is created equal.

A core element of today’s manufacturing systems is the challenge of managing extended supply chains. And these supply chains are subject to disruptions and the need to manage those disruptions.

(For a further look at the 3 Ms see 21st Century Air Capabilities https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=20246)

An excellent example of how to leverage what you are buying for the evolution of overall maritime security and defense capabilities are the intersections between the USCG’s National Security Cutter, the USMC’s F-35B and Osprey, and the USN’s LCS.

Shaping a collaborative approach for these three systems via the aviation assets and C4ISR systems is suggestive of a leveraging strategy.

The National Security Cutter is already deployed in the Pacific and provides a significant enduring presence in the Pacific. Any US strategy for the Pacific – which is clearly one of the key definitional areas for the next decades for US strategy – needs to operate from the Arctic to Australia. And here the USCG’s core endurance asset is a key player. The ship is currently being bought on a fixed priced contract, but the Congress is certainly not rewarding the Service for good behavior, but in any case the USCG needs more than 8 NSCs with 3-4 available in the Pacific.

As Admiral Currier, the Deputy Commandant (Mission Support) of the USCG, recently noted:

The National Security Cutter, in addition to being able to operate at high sea states, can launch and recover aircraft under those conditions. You have to understand the cutter’s utility as a weapon system.

It’s a platform for multiple, fast, small interceptor boats, surface craft, and also air assets, whether it be a helicopter, or unmanned aerial vehicle, which really extends the reach of the cutter significantly. We have a larger capacity for the small, fast boats, the interceptor boats. We can carry three vice one or two on a 378. The NSC is a sea base for fast response small boats and helicopters or virtually any specialized force for dealing with a wide spectrum of threats.

We’ve proven this concept repeatedly with interdiction of narcotic go-fasts in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific. With a Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), or with the use of non-USCG national assets, the ship is able to detect, monitor, and be in position to launch its helicopters, which will stop the suspect vessel, followed by the small boat boarding team.

It is a complete package. It capitalizes on external cues, intelligence, and airborne maritime patrols to develop a picture of the area. With the available maritime domain awareness, it can prosecute threats using its fast, armed, small boats, and its armed helicopters.

https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=22060

This asset provides an enduring presence asset globally, which can work with other USN, USMC or USAF assets in delivering global security solutions essential to 21st century operations.

And the NSC can fit into the puzzle of managing security and defense threats along with the other new assets being shaped by the USMC and the USN. The USMC intends to deploy the F-35B and the Osprey on its Amphibious Ready Group and these new assets significantly change the capabilities of the ARG and the ability of the ARG to work with other USN and USCG and USAF assets.

Yet the F-35B “debate” focuses on the IOC cost of the plane, not the value it brings to maritime transformation and the enablement of the joint force.The F-35B brings electronic warfare and cyber operations capability to the ARG; it provides C4ISR to command aviation and maritime assets; and it can redeploy to austere airfields to support ground operations across the spectrum of security and defense operations. And oh by the way can get places fast with its supersonic capabilities.

And coupled with the Osprey, which has only barely begun to be fully connected to a networked force, a newly enabled ARG is emerging. As General “Dog” Davis, currently the Commander of the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing at Cherry Point, North Carolina, has argued:

Our MEUs have never been used as effectively as they are today. These new capabilities are going to make them exponentially more potent and useful to our nation’s leadership.

The F-35Bs give the new ARG a very high-end air superiority fighter, that’s low observable if I want it to be. I can roll from Air to Air to Air to Ground quickly and be superior to all comers in both missions. That’s bad news for our adversaries. I can use the F-35s to escort the V-22s deep into enemy territory. With those V-22s we can range out to a 400-500-mile radius from the ship without air refueling. I can go deliver Marines deep in the enemy territory or wherever and do it at 250 miles an hour, so my speed of action, my agility is exponentially increased, and I think if you’re a bad guy, that would probably give you a reason to pause. It’s a very different animal that’s out there. We are good now, but will be even more so (by more than a factor of two in the future).

I also have significant mix and match capability. And this capability can change the impact of the ARG on the evolving situation. It is a forcing function enabled by variant mixes of capability. If I wanted to strip some V-22s off the deck, to accommodate more F-35s – I could do so easily. Their long legs allow them to lily pad for a limited period of time — off a much large array of shore FOBs – while still supporting the MEU. It’s much easier to do that in a V-22 than it is a traditional helicopter.

I open up that flight deck, or I can TRANSLANT or PAC additional F-35s. If I had six on the deck and I want to fly over another six or another four, we could do it rather quickly. Now the MEU has ten strike platforms. So if I need to have a TACAIR surge for a period of time, that deck provides a great platform for us. We’ve got the maintenance onboard that ship, so we can actually turn that Amphib very quickly from being a heliocentric Amphib to a fast jet Amphib. Conversely, I could also take the F-35s off, send them to a FOB and load it up with V-22s, 53Ks, or AH-1Zs and UH-1Ys. Flexible machines and flexible ships. The combination is exceptional.

We will have a very configurable, agile ship to reconfigure almost on a dime based on the situation at hand. I think the enemy would look at the ARG as something completely different from what we have now. I think we have to change the way we do things a bit in order to allow for that, but I think we will once we get the new air assets. The newly enabled ARG, or newly whichever the term you’re using, will force our opponents to look at things very differently. We will use it differently, and our opponents are going to look at it differently.

https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=17319

And of course, the USMC helos can land on the NSCs and support the higher end operations and needs for the NSCs as DoD assets. And narco and terrorist elements are using higher end capabilities such as mini-subs and fast planes, for which an overlap in ARG and NSC operations can provide a potent mix.

Now let us add the new Littoral Combat Ship to the mix. Again, no platform fights alone and in the new fiscally constrained environment driving maximum values from any new platform purchase is a sound idea. And as one builds collaborative con-ops across the joint force, a more effective power projection force can be shaped.

These two forces – the LCS and the newly configured ARG – can be conjoined and forged into an enlarged littoral combat capability. But without the newly configured ARG, and the core asset, the F-35B, such potential is undercut.

This is a good example of how buying the right platform – the F-35B – is part of a leveraging strategy whereby greater value is provided for the fleet through the acquisition of that platform. building blocks

In a time of fiscal stringency, good value acquisitions need to be prioritized. Such acquisitions are able to leverage already acquired or in the process of being acquired capabilities and provide significant enhancement of capabilities.

They are high value assets, both in terms of warfighting and best value from an overall fleet perspective.

The USN-USMC amphibious team can provide for a wide-range of options for the President simply by being offshore, with 5th generation aircraft capability on board which provides 360 situational awareness, deep visibility over the air and ground space, and carrying significant capability on board to empower a full spectrum force as needed.

Now add the LCS. The LCS provides a tip of the spear, presence mission capability. The speed of the ship allows it to provide forward presence more rapidly than any other ship in the USN-USMC inventory.

It was said in fighter aviation “speed is life” and in certain situations the LCS can be paid the same complement. The key is not only the ships agility and speed but it can carry helicopters and arrive on station with state-of-the art C4ISR capabilities to meld into the F-35B combat umbrella. Visualize a 40+ knot Iron Dome asset linking to Aegis ships and the ARG air assets.

Inserting an LCS into the Maersk Alabama incident can see an example of the impact of speed. As one naval analyst put it, the impact would have been as follows:

· LCS at 45kts would have been on scene in less than 7 hours (6.7), or 37% sooner than a ship transiting at 28 kts.

· LCS fuel consumption for such a sprint 40% less than the 28 kt sprint.

· LCS would consume less than 23% of her fuel capacity in such a sprint.

· A helo launch within 150 nautical miles from Maersk Alabama puts helo overhead within four hours (4.3) from the time of the initial tasking.

· Two H-60’s permits LCS to maintained a helo overhead Maersk Alabama for a sustained period of time.

With a response time of four hours the probability of thwarting a piracy attack is increased—especially if the naval ship is called upon the first realization of the targeted ship’s entry into piracy infested waters.

If an LCS was tasked to respond when Maersk Alabama encountered the first group of pirates craft on 7 April 2009, it would have arrived on scene well in advance of the attack on 8 April and may well have prevented it.

And if you add the LCS to the USN-USMC amphibious team you have even more capability and more options. As a senior USMC MEU commander has put it:

You’re sitting off the coast, pick your country, doesn’t matter, you’re told okay, we’ve got to do some shaping operations, we want to take and put some assets into shore, they’re going to do some shaping work over here. LCS comes in, very low profile platform. Operating off the shore, inserts these guys in small boats that night. They infill, they go in, their doing their mission.

The LCS now sets up — it’s a gun platform. It’s a resupply, refuel point for my Hueys and Cobras. Now, these guys get in here, okay. High value targets been picked out, there is an F-35 that’s doing some other operations. These guys only came with him and said hey, we have got a high value target, but if we take him out, we will compromise our position. The F-35 goes roger, got it painted, got it seen. This is what you’re seeing, this is what I’m seeing. Okay. Kill the target. The guys on the ground never even know what hit them.

https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=21129

By shaping a pull rather than push transition strategy, these new platforms WHICH ARE ALREADY BEING bought can provide for new capabilities by shaping collaborative con-ops.Significant savings come after having made the transition for older less fuel efficient and environmentally unfriendly 40-50 platforms, which suck up sustainment dollars.

To provide simply one example would be the impact of the F-35 on logs bills. Shifting from the legacy air fleet to the F-35 fleet will save trillions of dollars in operational support. Although the headlines were generated on the more than 1 trillion support costs of the F-35 fleet in 2065 dollars, what was missed that the legacy fleet in those very 2065 dollars would cost more than 4 trillion dollars.

The plane has been designed to optimize maintainability and to reduce the amount of touch labor on the plane by at least 30%. And the fleet commonality will lead to significant ability to operate, deploy and sustain fleets of aircraft.

Recently, retired head of Marine Corps Aviation General Trautman hammered the first point home.

Affordability is the balance of cost and capabilities required to accomplish assigned missions. For over a decade the Marine Corps has avoided the cost of new procurement during a time when the service lives of our legacy aircraft were sufficient to meet the missions assigned. However, in the near future, our investment in the capabilities of the F-35B will outweigh the unavoidable legacy aircraft operations and sustainment (O&S) cost increases we will incur with the F/A-18, AV-8B, and EA-6B.

The O&S costs of legacy aircraft across DoD have been increasing at an average rate of 7.8% per year since 2000. The operational lifetimes of legacy aircraft are being extended well beyond their original design limits. As a result, we have been continually engaged in a struggle to maintain operational readiness of our legacy aircraft due largely to the increasing age of the aircraft fleet. Early in an aircraft’s life cycle, the principal challenge is primarily attributed to the aging proprietary avionics systems upon which the user depends for warfighting relevance; later it is maintenance of the airframe and hardware components that are become the O&S cost drivers.

The Marine Corps strategy for the last eleven years has been to forego the procurement new variants of legacy aircraft and continuing a process of trying to sustain old designs that inherit the obsolescence and fatigue life issues of their predecessors. Instead, we opted to transition to a new 5th generation aircraft that takes advantage of technology improvements, which generate substantial savings in ownership cost. The capabilities of the F-35B enable the Marine Corps to replace three legacy aircraft types and retain the capability of executing all our missions.

This results in tangible O&S cost savings.

A common platform produces a common support and sustainment base. By necking down to one type of aircraft we eliminate a threefold redundancy in manpower, operating materiel, support services, training, maintenance competencies, technical systems management, tools, and aircraft upgrades. For example:

Direct military manpower will be reduced by 30%; approximately 340 officers and 2600 enlisted.

· Within the Naval Aviation Enterprise we will reduce the technical management requirements the systems requiring support by 60%.

· Peculiar Support Equipment will be reduced by 60%; down from 1,400 to 400 line items.

· Simulators and training support systems will be reduced by 80%; five different training systems will neck down to one.

· Electronic Attack WRA’s will be reduced by 40% and replaced with easier to support state of the art digital electronics.

· The Performance Based Logistics construct will nearly eliminate macro and micro avionics repair, and intermediate propulsion support functions.

· Airborne Armament Equipment (AAE) will be reduced by over 80% with the incorporation of a multi-use bomb rack.

Compared to historical parametrics we expect our overall O&S costs to decrease by 30%.

The key to enabling these reductions is to evolve our supportability concepts, processes and procedures instead of shackling ourselves to a support infrastructure built for legacy aircraft. We need to be innovative and ensure our sustainment posture keeps pace with technology advancements and global partnering synergies. Working together with industry, the Marine Corps is intently focused on the future as we seek innovative cost effective sustainment strategies that match the game changing operational capabilities resident in the F-35 Lightning II.

https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=10063

The impact of fleet operations was highlighted by retired General Cameron, now working on the F-35 program with Lockheed Martin. Cameron as a retired USAF general in charge of maintenance highlighted the fleet consequences of shifting form F-16s to F-35As for the USAF.

The real beauty of the F-35 program is the fact that you can look out across the entire fleet, all the international partners, all the domestic partners, and tell immediately if there are systemic fleet wide issues. The program can share assets to ensure a surge capability to wherever it’s needed and can share the robust supply chain that’s already established on the F-35 production line. Our experiences with the F-16 highlight another major advantage of the F-35 approach. The F-16 has been a highly successful program. However, configuration management has been a challenge because it has been handled at the individual service level. Therefore, there are roughly 130 configurations of the F-16. The operators, when prosecuting the air battle, have to know the precise configuration of each F-16 in order to know what capabilities it brings to the fight. The sustainment of the F-16 is even more challenging with spares not being interchangeable among F-16 variants. The F-35 is a common configuration so interoperability is the key in both operations and sustainment.

https://www.sldinfo.com/?p=12899

One could simply note that the views of such warfighters are simply bypassed in making wild assumptions about future life-cycle costs. An alternative approach would be to examine how the F-35 as manufactured leads to significant REDUCTIONS in touch labor time and to ENHANCED operational tempo, which in turn lead to COMBINED reduction in maintenance costs with enhanced, combat efficiencies.

In conclusion, the combining of the withdrawal from Afghanistan and Iraq, the sizing down of Big Army, and leveraging the new platforms already being built, the retirement of older platforms and systems can together form an acquisition strategy to shape the new US power projection capabilities for the 21st century.If one simply downsizes a skewed force structure of the last 10 years, an historic opportunity would be missed.

First published in Common Defense Quarterly, Fall 2011