By Karsten Von Hoesslin, Senior Analyst, Risk Intelligence

Strategic Insights, No. 30, February 2011

09/25/2011

Overview

A considerable increase in reported incidents occurred between 2009 and 2010 with elevated levels of sophisticated piracy and armed sea robbery in the South China Sea, the Sulu Sea, and nearing the end of 2010, the Singapore Strait. In 2010, piracy/armed sea robbery increased in all three aforementioned areas with a number of notable new developments.

South China Sea

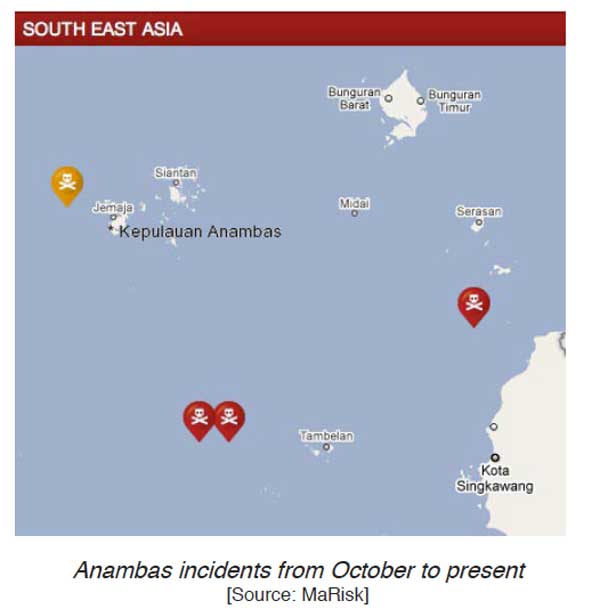

Incidents in this area were of two types: tug hijackings along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia and piracy attacks within the shipping lanes to the northwest of the Anambas Archipelago.

There were three notable cases of tug hijackings; all were recovered, however, due to a swift response by maritime enforcement agencies as well as information sharing through ReCAAP channels. Since the last incident involving the tug ATLANTIC 3 on 27 April 2010, there have been no new reported cases. Additional incidents involving suspicious activity continued to occur throughout 2010, which were connected to illegal bunkering operations such as the case with the BINA MARINE 51 on 11 June 2010.

Illegal bunkering, although more common in the eastern Singapore Strait, has increased sharply since 2008, correlating with the global economic slowdown. In addition to medium sized vessels bunkering illegally in the Singapore Strait, tugs are suspected to be playing an increasing role in illegal bunkering in the southern South China Sea.

Robberies of vessels in transit increased in the second quarter of 2010 off the Anambas Islands. The unique cluster piracy was increasingly fine-tuned where the syndicate targeted up to six vessels within a seven-day period. As of June 2010, incidents began occurring further to the east in the Natuna Archipelago and to the south off the Kalimantan coast including Serasan Island as well as the Tembelan Archipelago.

As the robbers increasingly targeted vessels to the south closer to Kalimantan, they decreased their focus off the Anambas Archipelago and minimized their attacks to two-three per cluster. They also increasingly moved back to Indonesia’s territorial waters after the first robbery knowing very well that foreign anti-piracy patrols would be active after the first incident within a cluster pattern.

Throughout 2010, the robbers enhanced their modus operandi in boarding tactics off the Anambas Archipelago by minimizing the time spent on the target vessels and focusing specifically on the Master’s safe. The most recent incidents that occurred off the Tembalan Archipelago showcased robbers boarding the vessel by night and holding an able body seaman captive and taking him to the Master’s cabin without even interfering with the navigation of the vessel or letting their presence be known on the bridge. Since August 2010, incidents off the Anambas Islands tapered off and moved closer towards the Kalimantan coast and by the end of 2011, short of two clusters off the Tembalan Islands, activity appears to have ceased in this area for the time being.

Singapore Strait

Armed sea robbery in the Singapore Strait was mostly focusing on ships at anchor in the eastern strait off Johor. A smaller and more simplistic syndicate was responsible for the bulk of boardings at anchor. They were suspected to have been operating as a tank cleaning crew in the daytime. At night, they return to specific softer targets of opportunity and rob them of small effects including crew valuables or ship’s stores before retreating back to Batam Island.

These incidents showed low levels of violence and sophistication. In the fourth quarter of 2010, however, they were complimented by a new syndicate displaying far more sophistication and tenacity. The new syndicate, based on Belakang Pedang, began targeting low freeboard vessels in transit (such as tugs) as well as occasional vessels at anchor of Tanjung Piu in the western Singapore Strait.

These incidents showed low levels of violence and sophistication. In the fourth quarter of 2010, however, they were complimented by a new syndicate displaying far more sophistication and tenacity. The new syndicate, based on Belakang Pedang, began targeting low freeboard vessels in transit (such as tugs) as well as occasional vessels at anchor of Tanjung Piu in the western Singapore Strait.

Of concern was this new syndicate’s modus operandi in holding crewmembers captive as well as arriving on scene better armed and possession of at least one handgun. In one incident in November 2010, the robbers even discharged their weapon during a boarding. Overall, the boardings have been carried out swiftly and increasingly resemble the tactics of the syndicate responsible for piracy attacks in the southern South China Sea.

Sulu Sea

Although incidents are still heavily under-reported, notable incidents did occur within the region in 2010, namely off the Sabah coast. In addition to well-armed piracy incidents, there were four reported hijackings against fishing trawlers. A specific syndicate based in the Philippines that is launching into Malaysian waters and targeting both tugs and fishing trawlers carried these out.

Although incidents are still heavily under-reported, notable incidents did occur within the region in 2010, namely off the Sabah coast. In addition to well-armed piracy incidents, there were four reported hijackings against fishing trawlers. A specific syndicate based in the Philippines that is launching into Malaysian waters and targeting both tugs and fishing trawlers carried these out.

Factors affecting piracy incidents

Jurisdictional issues

The primary factor at play in South East Asia is the continued abuse of jurisdictional boundaries, whether in the Anambas Islands, the Singapore Strait, or off the Sabah coast in the Sulu Sea. The ability for suspects to venture back into their territorial waters after raiding vessels in another nation’s or international waters will continue to be the primary obstacle for law enforcement agencies that are taking maritime security seriously.

In both the Singapore Strait and Sulu Sea, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) is combating armed sea robbery incidents. However, in their respective areas, the Indonesian and Philippine syndicates quickly return to their home waters to avoid pursuit from the MMEA.

In light of the Singapore Strait syndicate being based on Belakang Pedang the group can return to their home island, which sits a comfortable 21 nautical miles from the western anchorages off Tanjung Piu and 25 nautical miles form the eastern anchorages.

Furthermore, the maritime border sits less than six nautical miles from each of the anchorages and primary target locations. Vessels that are boarded in transit such as tugs are practically running the boundary line, which makes an escape back to Indonesian waters relatively easy.

Continued global economic slowdown

The global shipping crisis has also been credited in playing a role in piracy and armed sea robbery incidents in the region, namely in the eastern Singapore Strait. Vessels at anchor over extended periods of time off the Johor coast are targets of opportunity by both robbers who work as tank cleaners and legitimate bunkerers in the day or by more advanced syndicates – both based in the Indonesian Riau Islands.

In nearly all cases, the vessels are robbed of ship’s stores and occasionally of crew effects that are easily accessible, although robbers never attempt to target the Master’s safe, which typically would not possess a large sum to begin with due to the ship’s inactivity and anchorage. Wider criminal networks

Wider criminal networks, such as the Orang Butong Group that has an extensive reach spanning from the southern Philippines to Sulawesi to the Riau Islands, play a key role in smuggling activities as well as limited piracy operations in the region. Smaller networks, often associated with larger syndicates, including the Orang Butong, remain active in the southern Philippines, the Riau Islands, and off the Kalimantan coast.

Larger criminal networks are evident in the hijacking cases where pre-arranged buyers were secured prior to the hijacking, internal information concerning the tug’s movements was leaked, and a financier fronted the operation.

Law enforcement

Law enforcement agencies continue to increase their capacity in combating maritime crimes in South East Asia, but are also challenged by the jurisdictional abuse of syndicates operating in foreign waters.

As indicated earlier, maritime agencies such as the Singapore marine police/coast guard and the MMEA struggle in interdicting suspects as they flee into Indonesian and Philippines waters respectively.

Law enforcement agencies also differ in priorities: while the MMEA has focused on piracy and armed sea robbery and human smuggling, Singapore remains concerned about contraband smuggling and armed sea robbery incidents. Although piracy and armed sea robbery correlates between the two, Indonesia, for example, has put illegal fishing and timber smuggling at the forefront of its interests.

Overall, however, law enforcement capacity building and coordination continues to improve maritime security within the region’s waterways. This is particularly the case with Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and increasingly Vietnam. Indonesia and the Philippines continue to face obstacles ranging from internal bureaucracy, identity, and, unfortunately, corruption. However, it is possible to ascertain that both nations’ capabilities are improving, but simply not fast enough.

Information sharing

Information sharing has become a key asset to the region, which is partially due to the increased presence of ReCAAP. The organization played a key role in disseminating and sharing information during the hijackings of the tugs ASTA, PU2007, and the ATLANTIC 3.

Although not all littoral states are members of ReCAAP, the organization has healthy relationships with the non-members when it comes to sharing intelligence and information. Although ReCAAP cannot be directly credited for the recovery of all three tugs, in the cases of the ASTA and ATLANTIC 3, their role in information ex- change was crucial in assisting law enforcement agencies both during the hijacking phase as well as during the post-investigation phase.

Complementing organizational and governmental information sharing is the increased reporting by Masters and ship owners themselves. Incidents were grossly underreported in previous years. Attacks and increasingly failed attacks continue to filter in, however, which helps build better statistical databases and profile the modus operandi of specific syndicates….