11/17/2011 – As Nicholas Eberstadt, Murray Feshbach, and other scholars have noted, the Russian Federation has been experiencing an unrelenting demographic crisis throughout its two-decade history. Russia’s population has been shrinking more, and for a longer time, than almost any other country today.

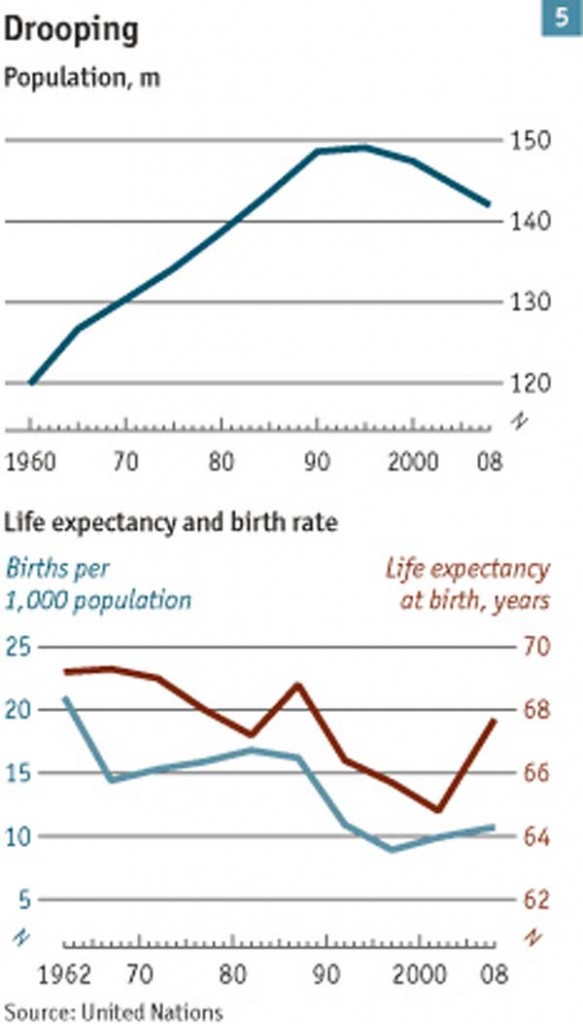

On average, 840,000 more Russians have died than were born each year since 1992. Since then, the country’s total population has reportedly fallen by close to 7 million people (almost 5%), with almost continuous year-on-year population declines. Russia’s depopulation crisis consists of a sharp decline in birth rates, accompanied by a sharp upsurge in deaths. According to official Russian figures, between 1992 and 2008, Russia officially registered 13 million more deaths than births. Not only has Russia lost population for 17 years in a row, but it is also projected by both Russian and international agencies to continue along that negative population growth path for decades to come, creating severe economic and security challenges for the Russian people and other countries that must help manage the consequences of Russia’s decline.

Russia’s depopulation, while more or less a country-wide phenomenon, is not uniform across all Russian territories; there is considerable regional variation within this overall national average. Not all oblasts even experience negative natural increase; in 2006, 20 of Russia’s 89 oblasts reported more births than deaths. These areas tend to be where ethnic and religious minorities are overrepresented. The areas in which there are the sharpest negative natural increases tend to be in the historical “heartland” of European Russia. The oblasts in which population increases are occurring, however, tend to be autonomous districts or republics, and only account for a small percentage of the overall Russian population. In 2006, the areas where depopulation was least severe were Dagestan, Ingushetia and Chechnya.

Unfortunately, these autonomous districts do not have the same economic significance of Russia’s affluent, metropolitan centers, St. Petersburg and Moscow. In both of these cities, deaths far outnumbered births in 2006, with St. Petersburg in particular ranking well above the national Russian death rate. In 2007, 90 percent of Russians lived in areas where the overall population was declining. The data show there is relatively less regional variation of fertility rates among Russia’s oblasts than in their mortality rates. Although Moscow and St. Petersburg enjoy better-than-average mortality levels, the areas surrounding them have some of the worst levels in Russia. It appears that proximity to affluence and amenities does not confer any advantages to suburban residents. The country’s most “western” or “European” areas generally have mortality levels above the national average, while oblasts that are overwhelmingly populated by non-Russian ethnicities such as Ingushetia, Chechnya and Dagestan do not.

Russia’s demographic crisis is unique in global and historical context.

Russia is defined as an “Upper Middle Income Economy” in the World Bank’s framework for ranking countries wealth based on per capita income, and after Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) adjustments, it ranks as one of the wealthiest states within this grouping. Yet Russia’s estimated life expectancy at 15 years of age is far lower than expected for a country with such a ranking. Combined male and female life expectancy at age 15 is lower than for some “lower middle income economies,” such as India. Male-only life expectancy at age 15 is one of the lowest in the world, lower than many of the World Bank’s “low income economies” such as Haiti and Benin. Russian male life expectancy at this age even ranks below the “failed state” of Somalia. Although Russia has experienced depopulation four times in the last century, the most recent occurrence is unique as it is occurring in peacetime rather than as a result of war or state-directed violence. The causes and solutions of the problem are therefore more complex than in the past.

The Russian Federation working age population has suffered from a severe health crisis. Over the four decades between 1965 and 2005, age-specific mortality rates for men in their 30s and 40s typically rose by around 100%, with women’s mortality rates rising by around 50%. This deterioration has seen a major divergence in health trends between Russia and the rest of Europe. According to the World Health Organization, by 2006 age-standardized mortality in the Russian Federation was over twice as high as in “pre-accession” states of the European Union (i.e., Western Europe). At the end of the Soviet era, the aggregated “new” EU states’ and Russian age standardized mortality rates were similar. Fifteen years later, Russian mortality rates had risen by 40% while the “new” EU states had recorded substantial health improvements following the demise of Soviet-style rule.

A driving force behind Russia’s depopulation is a significant drop in the number of ethnic Russians. Between the 1989 and 2002 censuses, the present-day Russian Federation’s population fell from 147 million to about 145.2 million, a drop of about 1.8 million. Over that same period, the reported share of ethnic Russians within the country declined as well: from 81.5 percent to 79.8 percent. These numbers indicate a drop of nearly 4 million ethnic Russians within that time period. However, during the same period, the Russian Federation absorbed a net influx of approximately 5 million immigrants, and a large proportion of these immigrants appear to have been ethnic Russians from former Soviet republics.

Although Russia experienced a dramatic drop in births during the “transition” period after Soviet Communism, low levels of fertility today cannot still be attributed to “systemic shock.” Indeed, low fertility rates have been a consistent trend in modern Russia, both during (although the Gorbachev era was an aberration), and after Soviet rule. Russia’s fertility rates have consistently ranked among the lowest in Europe, and are far below the necessary levels required for long-term native population replacement. Ethnic variation is also evident in fertility trends, as today ethnic Russian women record the lowest number of births apart from Russian Jews.

The Russian Federation’s changing trends on the family and fertility are also affected by trends in marriage and divorce rates. Marriage in modern Russia is both less common and less stable than in recent history. In 2005, the total number of marriages was down one fourth from marriages in 1980 and the divorce rates have been steadily rising since the end of the Soviet era. The divorce-to-marriage ratio has also increased greatly in this period. Areas of non-Russian ethnic dominance are again the exception to these nation-wide trends. Dagestan, Ingushetia, and Chechnya and other areas with large concentrations of Muslims have the lowest divorce-to-marriage ratios.

In 1990, the end of the Soviet era, divorce was not uncommon. Yet a Russian woman could enter her first marriage and stand a 60 percent chance of remaining in wedlock by age 50. By contrast, due to a plunge in nuptiality and a rise in divorce rates, in 1996 less than a third of women would remain in their first marriage until age 50. In addition to divorce rates, out-of-wedlock childbearing has also seen a sharp increase. In 1980, fewer than one newborn in nine were born out of wedlock. Yet by 2005, the country’s illegitimacy ratio was approaching 30%–a near tripling of the figure in 25 years. Perhaps predictably, there is a greater ratio of illegitimate births in rural regions than in metropolitan centers, with out-of-wedlock births representing 25 and 34 percent, respectively. In the country’s most remote regions, Siberia and the Russian Far East, nearly half of all births are out-of-wedlock.

Increasingly easy migration into, out of, and within the Russian Federation has been one of the few positive demographic trends following the demise of the Soviet Union. The ease of personal movement is partly due to changes in Russian law and partly to the globalization of transport and communication, a global change that Russians could not fully experience under communism. A fraction of the Russian populace is currently caught in a poverty trap that hinders or prevents domestic relocation in search of a better life. However, the portion of the population that does move is supporting the “New Russian Heartland” hypothesis, which argues that market forces will move the population of Russia westward and to the south. This has helped bolster the population of Moscow; even though it only constituted 6% of the population of Russia in 1989, its population boost accounted for 25% of the country’s internal migration. It now accounts for 7.5% of the country’s population.

Immigration into Russia has helped cushion the country’s demographic decline.

Russia’s population would have fallen even more had it not been for a net increase in in-migration in recent years. Since the beginning of the 2000s, Russia has become the country with the second highest immigration rate in the world, after the United States. Russia is estimated to have close to 10 million migrant seasonal workers, most of whom come (illegally) from the former Soviet republics of the Caucasus (Azerbaijan in particular) and from Central Asia (especially from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan). The implications for this increased immigration are significant for Russian economy. The overwhelming majority of migrants are of working age and seeking employment.

While immigration has significantly helped develop Russia economically, this increase in migration brings up questions of ethnicity and assimilation in Russia. Despite the Russian constitutional mandate of equality regardless of ethnicity, language and origin, the Russian Federation is distinctly a Russian state, consisting of: a Russian political tradition, a culture profoundly Russian, and a Russian lingua franca (with over 92% of the non-Russian population reporting a command of the Russian language).

A specific ethnic situation in Russia has been the “Muslim” population (which is more a reflection of ethnicity, not religious practice). The Muslim states surrounding Russia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan) all have much lower per capita incomes than Russia, leading to increased economic incentives to immigrate. In addition, once they enter the country, Muslim communities tend to have much higher fertility rates and lower divorce and higher marriage rates, leading to stronger and larger families. While Muslims increasingly immigrate to the Russian homeland (now constituting roughly 14.7 million people, or around 10% of the overall population), many Russians have emigrated to countries that have higher incomes than Russia (America, Germany, and Israel specifically).

Based on the current situation and trends affecting the Russian Federation, it is possible to offer bounded forecasts of its future size and composition. The United Nations Population Division (UNPD) project that Russia’s population in 2025 could range from a high of about 137 million to a low of about 127 million people. For the year 2030, UNPD forecasts range from 135 million to 122 million. The U.S. Bureau of the Census projects that the Russian Federation’s population will be 128 million in 2025 and 124 million in 2030.

Russian experts also predict that Russia’s population would amount to less than 136 million in 2025.

There is no historical example of a society that has demonstrated overall economic growth while contending with a population decline of that magnitude. The economic implications of this health deterioration are dramatic. Excess mortality rates, caused by negative natural increase and a deterioration of public health, adversely affect labor productivity now and for the future.

Continuing immigration of ethnic Russians would appear to be a prerequisite for Russia to maintain its current proportion of ethnic Russians within its borders.

The 1989 Russian census reported that there were about 25 million ethnic Russians living within the borders of the USSR, but beyond the Russian Federation. Following the turn of the new century, that number has shrunk to fewer than 18 million. This shrinking of the Russian diaspora by nearly 30 percent has several possible explanations.

First, roughly three million ethnic Russians may have migrated into the Russian Federation.

Second, a proportion of these Russians may have changed their ethnic self-identities to conform to post-USSR realities in their new homelands.

Third, this Russian population abroad may be affected by the same demographic issues Russians face within the Federation, such as early mortality, meaning that millions of these ethnic Russians could have died during the 1990s. If this is the case, the “reserves” of ethnic Russians living abroad will continue decrease in the future.

The decline of the Russian population poses threats to economic growth and to Russian security efforts. (Credit Image: Bigstock)

The decline of the Russian population poses threats to economic growth and to Russian security efforts. (Credit Image: Bigstock)

The number of ethnic Russians moving to Russia appears to have declined during the last decade in any case. Despite the booming Russian economy in the 2000-2006 period, the inflow of ethnic Russian migrants fell sharply to less than 100,000 each year, compared with an average of 433,000 for each of the previous seven years. Many of those ethnic Russians living outside Russia who wanted to return to their motherland have already done so, while those who have remained in the “near abroad” seem content in their new countries, where many of them were in fact born and have lived all their lives.

Meanwhile, a Russian government program to encourage descendants of Russian ancestors to return back to Russia has had minimal impact. The program provides eligible participants with help making the move and with employment assistance once in Russia. Despite spending about $300 million on the program, of the estimated 25 million eligible persons, only 10,300 had moved back as of 2009. Even if the entire Russian diaspora were to resettle within the Russian Federation, the influx would be insufficient to keep either Russia’s total population or its working age population groups from sinking below their 1995 levels by the year 2050.

These trends suggest that the proportion of Muslims in the Russian Federation will increase over time. There is no universally accepted number for the exact population of Muslims living in Russia. The Russian census does not collect information on religious affiliation. Thus, any data-based estimation of Russia’s Muslim population must be limited to examination of population totals of ethnic groups with a Muslim historical or cultural background. Russia’s nationalities of Muslim heritage accounted for 14.7 million people in Russia in 2002—just over 10 percent of the country’s total population that year. Given the negative natural increase, mortality and fertility rates of ethnic Russians today, an increase in the fraction of Muslims living in the Russian Federation is likely.

Another adverse security development is that the Russian Far East has experienced net out migration every year since the end of the Soviet Union and its system of subsidies. Since 1989, the region has experienced depopulation rates of 14% to nearly 60% in some places. This is most likely because formerly state-controlled cities and production areas in the east fell apart following the fall of communism, giving little forced incentive for citizens to remain in these fairly barren lands. In addition, despite its massive resources, the actual demand for labor in the Russian Far East is at best in the hundreds of thousands, not millions. This makes outmigration economically rational and desirable. This trend, combined with the fact that the Russian Far East borders North Korea and China, raises unwelcome security questions. In the near term, instability in North Korea could lead to a mass exodus of refugees into Russia.

Over the longer term, these demographic disparities beg the question of Chinese aims regarding neighboring Russian territories. Since 1988, immigration into the Russian Far East by Chinese laborers has increased, but estimates of Chinese immigrant population vary wildly. Russian fears of a “yellow peril” have been exaggerated. As can best be determined, the reality is that only a few hundred thousand Chinese migrants live and work in the Russian Far East. Additional Chinese migration into the depopulated and economically depressed Russian Far East could actually prove beneficial to the regional and Russian economy, but it would perhaps weaken the region’s Russian-based national identity and threaten the country’s long-term territorial integrity.

An additional adverse security impact of Russia’s declining population is that the Russian armed forces will have declining personnel resources in the years ahead. Five years ago Russia had more 18-year olds than ever before in its history. But within the next ten years, that number may drop to the lowest in 100 years. The pool of prospective military recruits, under the current staffing formula, is set to fall by almost two-fifths between 2008 and 2017. Another complicating issue is the likely changes in the ethnic composition of the draft pool—that is, a growing share of Muslims. This prospect has produced near panic within the military establishment. Its members propose increasing the pool of draft-eligible men by inducting less qualified recruits, extending soldiers’ terms of service, and employing other options that would have negative consequences in other areas. More likely, this unavoidable reality of a very much reduced pool of men will lead to more radical military reform proposals.

Russia’s foreign rivals and partners will have to manage the negative consequences of a decreasing Russian population, which include lower economic performance, population disparities along potentially contested international borders, fewer potential military recruits, and the general issue of what Russian leaders might do when their lofty ambitions encounter these inescapably negative demographic facts. Will Russian leaders scale back their ambitions, become more risk averse, and more readily cooperate with the international community to compensate for Russia’s decreasing human potential? Or will they decide that drastic measures such as preventive wars and a nuclear weapons buildup are needed to compensate for their lost “mass mobilization” potential against foreign threats? Unfortunately, demographic analysis alone cannot answer this question.

Although Western economists can argue that the quality of human capital matters more than its quantity, Russian leaders see all these current trends and future projections as a grave threat to their country’s security. Economists note that recent history shows a negative correlation between a country’s population growth and its economic performance. The data for the 1970-2008 period, for example, shows that the slower a country’s population growth, the faster its per capita GDP increases. But in the view of Russia’s leaders, population decline calls into question the country’s “great power” status. The Soviet Union was the third most populous country in the world at the time of its death in 1990, ahead of the United States. Russia’s current population places it in eighth place in terms of national population size, and Russia appears to be falling further over time. It might be possible to increase Russians’ individual wealth and welfare even with aggregate population decline, but substituting quality for quantity in military forces requires Russia’s defense industry to do better at producing more effective weapons.