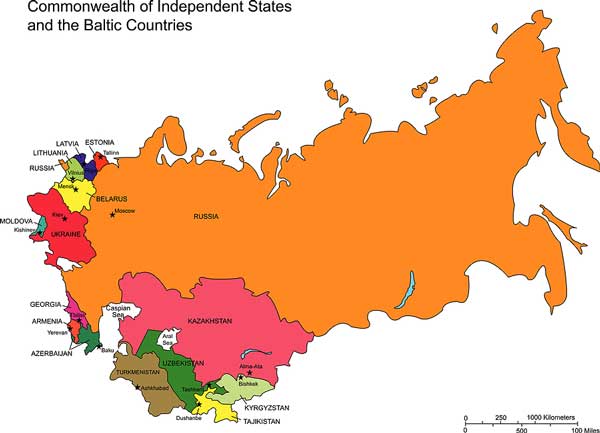

02/13/2012 – The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), consisting of all the former Soviet republics except for the Baltic countries, initially represented Kazakhstan’s most important regional institution after the USSR’s disintegration. On December 16, 1991, Kazakhstan became the last of the 15 former Soviet republics to declare the country’s independence. Five days later, Kazakhstan joined the new CIS, which effectively marked the end of the Soviet Union.

At its founding in 1991, President Nursultan Nazarbayev backed the creation of the CIS on the grounds that the “future relations of independent states will be underpinned by a spiritual unity of nations, fostered by many generations of our ancestors.” Kazakhstan proposed adoption of the CIS Development Concept and an associated action plan to outline priority areas for long-term cooperation among CIS members.

The CIS itself initially played a useful role in facilitating a “civilized divorce” among its members. Compared with the chaos that arose in the former Yugoslavia, another communist-dominated multinational state that had failed to resolve its underlying ethnic divisions, the disintegration of the Soviet Union occurred with less violence. For the most part, the leaders of Kazakhstan and the other newly independent former Soviet republics accepted the USSR’s administrative boundaries as their new national borders. Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the CIS for “clearly help[ing] us to get through the period of putting in place partnership relations between the newly formed young states without any great losses and play[ing] a positive part in containing regional conflicts in the post-Soviet area.”

The problems of achieving consensus among twelve combined with the organization’s weak, opaque, and inefficient institutions for making and implementing decisions make it difficult for the CIS to be an effective multi-national institution. (Credit image: Bigstock)

The problems of achieving consensus among twelve combined with the organization’s weak, opaque, and inefficient institutions for making and implementing decisions make it difficult for the CIS to be an effective multi-national institution. (Credit image: Bigstock)

The CIS achievements came at a time of deep difficulty for most of the Soviet republics, which were making the difficult triple transitions from an integrated socialist economic and political system to one characterized by newly independent states with varying degrees of free market economic systems and pluralistic political systems.

The first decade of the CIS was market by political disputes within the new countries; economic chaos within and among them; the rise of transnational criminal organizations, mass population movements, and extremist political and religious ideologies; as well as several vicious military conflicts involving various ethnic and paramilitary groups drawing out elements of the previous integrated Soviet armed forces. The most serious conflicts occurred in Tajikistan, Georgia, Moldova and between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh.

These conflicts soon froze under CIS-mediated truces. Often the peacekeepers were mainly Russian troops under Moscow’s control but cloaked under a multilateral cover. Unfortunately, neither the CIS nor anyone else has been able to resolve the conflicts between Armenia-Azerbaijan, Georgia-Russia, and Moldova-Transniester. The Georgia conflict thawed in August 2008 and the other two are vulnerable to the same outcome.

The CIS did enjoy some favorable conditions in its rudimentary stage, Its leaders, almost all of whom had been educated during the Soviet period, had a similar world outlook and a ready fluency in the Russian language. Many agreements are reached and disagreements circumvented thanks to the informal coordination that regularly occurs between the leaders and their ministers.

The CIS did initially help generate some security collaboration among its members. The leaders of Kazakhstan and Belarus, Russia, the three South Caucasus countries, and the other Central Asian states except Turkmenistan) signed a CIS Collective Security Treaty (CST) at their May 15, 1992, summit in Tashkent. It called for military cooperation and joint consultations in the event of security threats to any member. At the time to renew the treaty in 1999, Uzbekistan, Georgia, and Azerbaijan formally withdrew.

The CST signatories pledged to refrain from joining other alliances directed against any other signatory. The CST signatories also agreed to cooperate to resolve conflicts between members and cooperate in cases of external aggression against them. The main effect of the Tashkent Treaty was to help Russia legitimize its continued military presence in many CIS members.

After its first few years, however, the CIS ceased having a great impact on its members’ most important security policies. For instance, the agreement establishing a collective air defense network, which began to operate in 1995, had to be supplemented by separate bilateral agreements between Russia and several important participants such as Ukraine. Georgia and Turkmenistan withdrew from the system in 1997.

The influence of the CIS reached nadir in 1999, when Russia withdrew its border guards from Kyrgyzstan and its military advisers from Turkmenistan, while three members (Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Uzbekistan) declined to renew their membership in the CST.

Despite the CST, CIS governments proved unable to collaborate sufficiently to end the civil war in Tajikistan or establish a common front regarding the Taliban and related terrorist threats emanating from Afghanistan, exposing the weakness of the Tashkent Treaty at the time it was most needed. It was only in March 2000 that Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan finally announced the establishment of the long-discussed CIS antiterrorist center.

Some military activities still occur within the CIS framework. For example, Kyrgyzstan has hosted several CIS anti-terrorist exercises, beginning with “South-Antiterror-200.” It rehearsed resisting another Islamist terrorist incursion through Kyrgyzstan, which had occurred in 1999-2000.

More recently, the CIS Anti-Terrorism Center sponsored exercises in Kyrgyzstan last year. The “Berkut-Antiterror-2011” and “Yug [South]-Antiterror-2011” exercises occurred May 3-4 in Osh. The drills included law enforcement and special service personnel from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia and Tajikistan. The troops rehearsed combating hypothetical terrorists that had attacked buildings and seized vehicles. The heads of various CIS security agencies, special forces and law enforcement agencies observed the drills.

During the drill, Osh Mayor Melis Myrzakmatov said that, “The past decade has shown that the initiative of the CIS Council of Heads of State in creating the Anti-Terrorist Centre was timely and correct.” He noted that the past decade since its establishment has seen a number of terrorist groups active in the CIS region, including the al-Qaeda, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Islamic Movement of Eastern Turkestan, and Hizb ut-Tahrir, which many Western governments do not consider a terrorist group.

Myrzakmatov still considered such exercises valuable since “[s]uch command-staff exercises and training sessions are needed on a constant basis because they clearly demonstrate to the public that the authorities are taking steps in the fight against extremists and terrorists.”

In addition, Myrzakmatov added that, “We have to recognise that the elimination of Osama bin Laden could rally his supporters even more strongly,” he told Central Asia Online. “They could pool their strength to destabilise the Fergana Valley. This means we have to be ready for anything and the danger from the Afghan-Tajik border remains considerable.”

In October 2007, the member governments did agree to establish a special CIS body to supervise migration among their countries. Migration has been a recurring source of tension between the labor exporting countries of Central Asia and the recipient countries, above all Russia. Not only are the Central Asian migrants badly treated in Russia, but they are often the first to lose their jobs during a Russian economic downturn, as occurred in 2008.

The CIS has also established a corps of election observers that, by almost always certifying its members’ elections as free and fair, help dilute the typically more critical assessments of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), whose evaluation is nonetheless considered authoritative. For example, while the OSCE found the April 2010 presidential and January 2011 parliamentary elections in Kazakhstan flawed, the CIS monitors determined that it met all their requirements for a legitimate ballot.

A more recent preoccupation of some CIS governments has been exerting additional control over the Internet, still one of the freest communications media in teh former Soviet republics–under the rubric of combating cyber crime and cyber terrorism. In October 14, 2011, the CIS interior ministers adopted a draft strategy for CIS cooperation on this issue. Russian Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliyev said that, “These sorts of crimes tend to be international, which is why we should work together to fight them.”

Another official in the Russian Interior Ministry, Alexei Moshkov, observed that, “We think it should contain some practical measures for keeping the national information space from being used for destructive political and social means.” The CIS governments have been trying to promote such Internet controls at a global level. Moshkov explained that securing multinational agreement within the CIS framework helps their members advance this wider objective, observing that, “The high level at which it is being discussed will provide a strong impetus for the development of a global model for fighting cyber crime.”

One problem that became increasingly evident over time was that the CIS historically has had difficulties securing implementation of many of the economic, political, and security agreements its member governments have signed.

Although the institution does provide opportunities for dialogue among its members, especially among government ministries and agencies dealing with common problems such as customs and migration, and legislatures through the CIS Parliamentary Assembly, the lack of effective enforcement or oversight mechanisms severely limits effective cooperation. According to President Nazarbayev, of the 1,600 agreements formally adopted by the CIS, its members had signed and implemented fewer than 30% of them. Even Russian lawmakers ratify only a small percentage of CIS accords, making it hard to reconcile members’ conflicting legislation and policies.

The CIS did not fulfill Kazakhstan’s objective of establishing a system of collective security in the former Soviet Union.

The organization also failed to achieve the extensive degree of regional economic integration sought by the Kazakhstani government. By 2009, Kazakhstan was second in the CIS, after Russia, in terms of GDP per capita. But the CIS did not really help Kazakhstani businesses reach the potentially vast market of almost 280 million consumers.

Thus, as a collective institution, the CIS punches far below the aggregate weight of its individual members.

The members cover approximately one-sixth of the earth’s surface, possess large shares of important natural resources such as oil and gas, and have some five percent of the world’s population. Yet, they account for only three percent of international trade. Putin said trade volume within the CIS rose 48 percent in the first half of 2011 to 134 billion U.S. dollars. But many members conduct more trade and investment with non-CIS members than with their CIS partners. This dependence on external financing and commodity exports punished many CIS countries heavily during the recent global economic downturn. The current economic rebound rests on fragile foundations since they are highly vulnerable to negative spillover from the financial crisis in the European Union, a leading importer of many of their products.

Besides its structural weaknesses, policy differences among CIS members also have called into question the institution’s viability. Major frictions between Russia and other members have arisen over a number of issues. For instance, the CIS members have diverged over the appropriate prices for Russian energy and Russia’s restrictions on labor mobility. Plans to establish a CIS free trade zone have been repeatedly postponed due to the disparities among its members in terms of economic policies and attributes.

Similar divergences have been evident in the desire of some but not all CIS members to move closer to seemingly rival Western institutions like the European Union and NATO. The wave of color revolutions a few years ago widened divergences among the members’ political systems, with certain countries seeking to establish European-style liberal democracies and other regimes committed to preserving their authoritarian status quo. Some member governments see the organization primarily as a mechanism for consultations with fellow CIS leaders, a concept derisively referred to as a “presidential club” by its critics. Even such close CIS allies as Russia and Belarus are divided over key issues like whether to adopt a common currency and over the price other CIS members should pay for Russia’s oil and gas.

Ironically, a core weakness of the CIS—its limited means to enforce harmony regarding goals, policies, and values of its members—also probably will prevent its complete disintegration. Much more than the EU, the CIS encourages its members to pursue “multi-speed integration” arrangements in which the pace of integration varies by issue and the participants. Since it exercises so few limits on their freedom of action, these governments lack a strong reason to break with inertia and formally leave the organization. Instead, the CIS likely will persist, but as a decreasingly influential institution as its members redirect their attention and resources elsewhere.

President Nazarbayev has been pushing for years for a major restructuring and strengthening of the organization. At the July 2006 informal summit of CIS leaders in Moscow, he offered a comprehensive program for reforming the CIS that proposed concentrating reform efforts in five main areas: migration, transportation, communications, transnational crime, and scientific, educational, and cultural cooperation. Nazarbayev also suggested several cost-cutting measures that would have allowed for the more efficient use of the organization’s resources.

At the November 2007 meeting of CIS Prime Ministers in Ashgabat, Kazakh Prime Minister Karim Masimov called for the establishment of a common CIS food marketing and pricing policy. Masimov stated that “food prices have been growing lately so … our governments should draft specific measures and take specific steps for lifting administrative and other non-market barriers in food deliveries.” The CIS leaders decided to create a group of CIS agricultural ministers to develop a food market development strategy.”

Russian leaders have also supported Nazarbayev’s reform proposals. “It is our duty to pay close attention to cooperation with countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States,” Russia President Dmitry Medvedev observed during a May 2008 joint news conference with Nazarbayev. “The time has come for ties to be intensified.” Medvedev also endorsed the Kazakh government’s proposal to make energy cooperation the priority issue of the CIS agenda in 2009.

In 2008 the CIS heads of government endorsed “The Strategy of CIS Economic Development until 2020.” The following year, they approved an action plan for implementing its first phase. After more than a decade of difficult negotiations, the CIS governments unexpectedly agreed in October 2011 to establish a free trade area among themselves. Presumably reflecting concerns about the global financial crisis and other threats to their economic welfare, it provides for the gradual reduction in import and export duties and other impediments to free trade. But three of the CIS presidents declined to sign the agreement. And the CIS has had a perennial problem securing implementation of any agreement that is reached by its members.

The problems of achieving consensus among twelve governments with divergent political, economic, and security agendas–combined with the organization’s weak, opaque, and inefficient institutions for making and implementing decisions–have led to the stagnation and steady decline of the CIS relative to the other major multinational institutions present in Central Asia.

Perennial plans to reform its ineffective decision making structures have failed to achieve much progress. For the most part, the CIS members have ignored or failed to implement these reform proposals. Several CIS presidents have repeatedly not even bothered to attend the CIS heads-of-state summit. Other international organizations have therefore assumed the lead role in promoting multinational integration among the former Soviet republics regarding most other issues.

Credit Featured Image: Bigstock