2010-05-22

Everyone knows that the F-35 is a stealth aircraft.

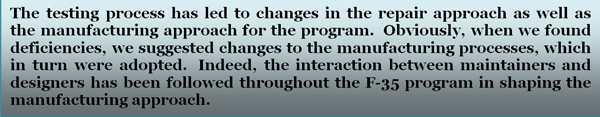

This is one element of what makes it a fifth-generation aircraft. But what is not widely known is that the stealth or low observable (LO) character of the aircraft is significantly different from other stealth aircraft like the F-22.

The F-35 LO capability is significantly more robust than legacy stealth, if one might call it that.

Indeed, the F-35 stealth is designed to leave the factory and to be maintained in the field, rather than having to come back to depot or the Fort Worth factory. In addition, the training of the maintainers for the LO repairs are being done at the partner level.

That is, if a coalition partner buys an F-35 it will be able to maintain it with the proper training (such as the one to be received at the Eglin AFB facility) and to do so in the field.

Although a significant aspect of the F-35 program, the LO repair facility has received scant attention in the vast literature commenting on the F-35. In January 2010, SLD sat down with Bill Grant, Lockheed Martin F-35 Supportable Low Observables Integrate Product Team Lead, in Fort Worth, Texas – a joint Lockheed-Martin – Northrop Grumman facility – to discuss the facility itself as well as the F-35 approach to LO maintenance.

***

LO Materials Repair:

– Tested for USN and USMC operational environment

– Designed to be used in the maritime environment

(Credit: Lockheed-Martin)

SLD: Would you explain the background of setting up the LO facility?

Bill Grant: We had the privilege of being able to work with complete access to data and experience of historic stealth programs, including the F-22. Our perspective was simply that LO was an afterthought from the standpoint of manufacturing, whereby stealth was added on to the aircraft. In our program, stealth is manufactured into the aircraft. The program recognized the LO repair needed to be focused on as an effort by itself. The repair development center was an early invention of the program and was given the resources to go out there and experiment with different material systems and to help refine them and then to incorporate them into a system level approach. We have developed repairs for each of the materials themselves and then as an entire system.

SLD: How would you describe the stealth LO capability of the F-35 compared to legacy systems?

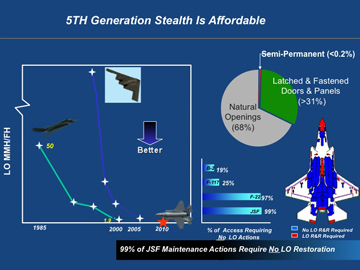

Bill Grant: Performance-wise, it is a very aggressive capability. From a design standpoint, it is a radical change from legacy systems. In legacy stealth, the stealth in effect is a parasitic application of a multiple stack-up of material systems done in final finish after the actual airframe is built and completed. In the case of the F-35, we’ve incorporated much of the LO system directly into the air frame itself. The materials have been manufactured right into the structure, so they have the durability and lifetime qualities. It makes them much more impervious to damage. It is a much simpler system with fewer materials to contend with.

SLD: In terms of the way you’re describing it, stealth goes from being a surface appliqué to becoming an integral part of the actual product being manufactured, is this correct?

Bill Grant: Exactly.

SLD: So this must have a significant impact on maritime operations. For example, the future of the F-35Bs and Cs should be a significant improvement over legacy aircraft, shoulden’t it be?

Bill Grant: Absolutely. The Navy and Marine Corps have set the benchmark for the LO repair facility program and approach. They work in the worst maintenance environments. It was the challenge we had to meet. So our material development effort and material qualification program was predicated and populated by requirements that were specifically suited for the Navy and Marine Corps.

We have the most extensive and aggressive material qualification in our history, probably in industry history. We have as many as ten times more coupons per materials being tested. We have engaged in a very aggressive approach to testing which has been developed with the military labs and the program office. We have worked with them to shape the most aggressive and most challenging test regimen from all of their different programs and their experience, and thereby compiled those experiences into our test matrix.

And the testing process has led to changes in the repair approach as well as the manufacturing approach for the program. Obviously, when we found deficiencies, we suggested changes to the manufacturing processes, which in turn were adopted. Indeed, the interaction between maintainers and designers has been followed throughout the F-35 program in shaping the manufacturing approach.

SLD: You’ve mentioned “ten times the coupons being tested.” What exactly does that mean?

Bill Grant: Well, we use little mechanical coupons. They are then used to do mechanical testing in corrosion and twisting and pulling, and those are representatives of all of the structural integrations of panels and substructure, and the material systems that spanned gaps in the panels and substructure. We test those coupons in those mechanical situations in both hot and cold extremes and we’ve yet to see any of those gaps open up. Naturally, if you can keep the gaps from opening up and introducing contaminants, the potential for corrosion is much lower.

We also have a large selection of similar types of coupons representative of various elements of the structure that are in exposure environments. These environments are either in the laboratory, in our salt bog, exposed to acid rains, or stack gas type of environment – a very, very aggressive environment that they’re out on exposure racks or at Battelle’s corrosion test facilities out in Daytona Beach, which is considered by the Air Force to be the most corrosion-prone area in the Continental-48.

Those coupons being tested, by the way, are in both pristine and in deliberately damaged conditions so that we’ve introduced damage that either the maintenance environment or manufacturing anomalies could represent so that we have a good test of what all the materials do in that environment.

SLD: One of the unique aspects of the F-35 program is how the Systems Development and Demonstration (SDD) phase has been shaped to front-load many manufacturing and maintenance capabilities prior to the full production run of the aircraft: isen’t the LO lab part of this process ?

Bill Grant: Absolutely. There has been tremendous investment both on our part and the government in the way that they configured the plan and the entire program to address these issues. Supportability, in general, and supportability of the LO system, specifically, was a highlight of the program. It’s one of the pillar elements of the program to ensure aircraft availability and affordability. Obviously, the issues of the past and the expense of maintaining LO on an airplane was of paramount concern to a fleet like the F-35, where there’ll be thousands of the airplanes flying and need to be globally operational and maintainable.

SLD: The program inherited a significant LO legacy capability given that Northrop Grumman and Lockheed are key partners in the program: could you elaborate on this heritage and how it has been leveraged?

Bill Grant: The legacy stealth programs – which to a lesser or greater degrees had to invent the technology in a stovepipe fashion – were on their own and they all essentially had to reinvent the wheel. In the F-35 program, we are partnered with Northrop Grumman and, as such, our team represents a 100 percent of the operational stealth experience in the industry in the world. My team and the LO sustainment area is comprised of half Lockheed and half Northrop Grumman employees. Most of the Northrop Grumman employees are actually retired Air Force LO maintainers who collectively have experience on all of the previous jets currently flying out there. And those that are retired have brought a tremendous wealth of innovation and experience so that they can improve on the conditions markedly for the maintainers of the F-35. We are not starting from zero. Leveraging this experience is allowing us to build a sustainable LO capability. We’re all about providing the maintainer weekends off by giving them systems that are durable and then easily maintained.

SLD: I understand that a core feature of the LO repair effort has been to shape approaches to sustainment that, in turn, have influenced design and manufacturing approaches to the aircraft. In other words, there has been a highly interactive process between the maintenance side and the manufacturing sides of the house.

Bill Grant: Absolutely. From day one, the supportable LO has been a key entity on the program and has had a profound influence on the very design of the airplane. In fact, the element that is manufactured into the skin was an initiative brought about by our LO maintenance discipline. We’ve also had a profound influence on the selection of the materials and then once they were decided upon, we helped refine the properties to make them more workable for field use. In addition, we’ve used the innovation of our team members to create tools and processes that are very easy and reduced the training burden so that they can be easily done in a unit-level environment.

SLD: The F-35 program is built around global partnerships and a globally deployed capability. What is the role of partners in the LO repair facility?

Bill Grant: The partners weren’t involved from the very beginning because our technology transfer agreements didn’t permit that for a while. But as of November of 2008, they have participated in what has become a real institution here. We have quarterly two-day hands-on familiarization courses where members from maintainers from all of the services and several partners come in and get some experience with the tools and the processes affecting the restorations and the repairs. That’s been a tremendous plus in terms of their input and shaping our understanding of what works and what doesn’t work, and we’ve modified our designs and our concepts accordingly. But mostly, they’ve provided a high-level validation that these tools and processes do, in fact, work for them, for both experienced and inexperienced LO maintainers, and that it’s doable in their environment.

SLD: So a lot of the LO maintenance will be done by the services and partners in the field?

Bill Grant: Yes indeed: we have no recognized need for any kind of return to depot or return to manufacturer for doing any type of LO maintenance.

Our system requirement was for end of life, which means that throughout the 8,000-hour service life of the jet, it is to remain fully mission-capable. So we anticipated that the amount of maintenance that would be done over the life of the airplane and anticipated that in the design. So when we deliver the jet, it’s delivered with a significant margin of degradation that’s allowed for all of these types of repairs over the life of the airplane, again, without having to return to the depot for refurbishment.

There may be some cosmetic-based reasons why the jet might go back to a facility to get its appearance improved, but from a performance-standpoint we recognize no need to do that. The unit-level maintenance will be adequate for maintaining the full-mission capability of the jet.

SLD: In entering the facility, I noticed you have a “door mat” of stealth that’s been there for some time. Can you comment on this “door mat?”

Bill Grant: Oh, the slab of stealth? That’s our welcome mat. Yes, we actually have one of the test panels that we use for assessing the stealth of the various materials. It represents a stack-up that’s consistent with the upper surface or the outer surface of the jet. It has the exact same structure and the primer and the topcoat system that you’ll find on the operational jets. And that gets walked upon every time somebody comes in or out of our lab area out there, the repair development center.

Occasionally, we take it up to test to see if there’s any electrical or mechanical degradation to the system and with around 25,000 steps across that system we have not seen any degradation whatsoever. So we have a great deal of confidence, however anecdotal that may be, that we have a very robust system.

———-

***Posted on March 22nd, 2010