Insourcing or the End of PBL?

The Obama Administration has focused on reform of acquisition practices across the public sector and the President has gone out of his way to target the private sector as a source of “outsourcing gone awry.” The President has hence called for greater responsibility in government oversight of the acquisition process as well as doing more of its own work to “save” money.

Ironically, a key part of this effort is the ending of performance-based logistics begun in the Clinton Presidency, as U.S. allies either further embrace or further innovate in having the private sector heavily engaged in both the management of and execution of logistics in order not only to achieve substantial savings and productivity gains, but also optimize their supply chain.

The Administration will “insource wherever possible to ‘save money’.” The “insourcing” phenomena is really about hiring public servants and reducing the role of private industry. What is not clear is how this saves money.

Indeed, interviews with a number of firms in the U.S. underscored that the U.S. government is in effect hiring back its former personnel which had retired and gone to the private sector and is paying them a premium to do so.

A senior USAF officer in charge of a major USAF facility told sldinfo that “our facility was always dependent upon the use of contractors. Now we have to replace those contractors and do so at cost increases of nearly double of what we were paying the private sector. The result is a reduction of output of the weapons development facility.”

The Value of Comparative Metrics

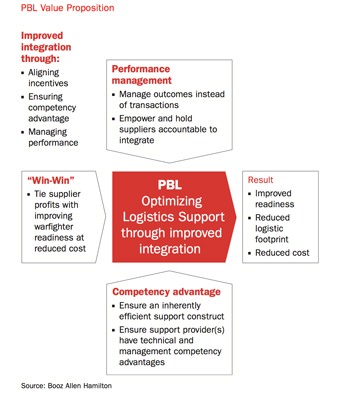

Performance-based logistics has become a target with the pursuit of such principles. The GAO has in several reports reviewing PBL underscored that the “cost savings from PBL have not been demonstrated. They are not auditable.” The GAO point is well taken and as a senior OSD official involved in sustainment and logistics told sldinfo, “we need to improve our efforts to understand and demonstrate cost savings from working with the private sector.

Yet one should note that the GAO does not audit the depot system, which does 50% or more of the U.S. logistics and sustainment efforts. Indeed, without auditing the depots, it is impossible to claim that there are cost savings in the offing by pushing more government work to the depots instead of having the private sector involved through a PBL or similar effort.

What is striking is how often assertions of future savings are simply not challenged.

A key case in point is the recent USAF decision to jettison the PBL system for the F-22. The PBL for F-22 has clearly demonstrated that the private sector delivered improved performance and availability of the aircraft.

In the case of the F-22, the irony is that in 2008 the USAF gave the PBL team the PBL system level PBL of the year award. Key success factors cited in the award were warfighter support, public-private partnerships, ownership costs reduction and sustainment system engineering teamwork. Another key discriminator cited in the award was ability to respond to changing ops tempos and warfighter needs.

Notably, as the F-22 fleet size has been caped and inevitably will go down in numbers for missions, one would think that USAF data indicated that a 15% improvement in Mission Capable rates and repair time reduced by 20% would count for more rather than for less in the period ahead.

Apparently not. According to Debra Tune, deputy assistant Air Force secretary for logistics, the government will save “billions of dollars” from bringing the work in-house. Although a good case of populist procurement rhetoric, what is not clear is what savings the USAF is referring to. There may be upfront reductions in expenditures in FY 2010 or 2011 but it is difficult to see how hiring new personnel or hiring back retired personnel saves money.

Even more to the point, under PBL, metrics for the payment of services by the private sector- and, even more important, management of the parts ordering chain – have clearly been established. A key advantage of PBL has been that the private sector delivers an outcome, and does so by buying parts in line with its determination of the flow of parts necessary to achieve a result [1].

The government does not. The government buys on annual budgetary cycles and based on bureaucratic estimates of parts required on an annual basis. Delivering to mission readiness is a metric one can understand; it’s more difficult to understand how the government now will save money from its own management of the supply chain.

Because the missing ingredient in the Administration’s treatment of “insourcing” and the end of PBL is simply that it will now have to manage the supply chain. For programs in production, prime contractors are the vortex of managing a difficult supply chafing process. The advantage of the PBL approach is simply that the contractor is in a position to maintain the supply chain with an eye to production and sustainment. Unless, the Administration has in mind going back to an Arsenal system, it is difficult to see how it will effectively do this.

But it is precisely what the USAF leadership is promising to do with the new tanker and the F35. Debra Tune added in an Inside the Air Force interview, “We consider support integration (CLS) role to be a core competency of the Air Force. We are moving back toward government product support integration.” [2]

Managing the Private Engineering Base

Another challenge facing the Administration will now be to manage the private engineering base supporting the sustainment process. The impulse towards PBL was driven by the inability of the government and the private sector to provide full transparency between the warfighter needs and the development and production engineers in the private sector. As a former senior acquisition official told sldinfo: “PBL allows the engineering talent in the private sector to be fully engaged in sustainment and modernization of systems. By putting the private sector in a leading role in shaping metrics for performance, the engineers were then in a position to shape more effective upgrade and modernization strategies.”

The new “government directed sustainment approach” then is reshaping the concept of how to acquire new products, and presumably ownership of the engineering process for modernization. Whereas the F-35 has had a clear approach to building a PBL sustainment system, now the USAF on its own has suggested it will not follow this approach.

The USAF will “back-fit” the new “approach” to existing PBL contracts, such as the C-17. It is difficult to find a sustainment approach more successful in readiness and performance metrics than the C-17, but Debra Tune tells us that “change” is necessary here as well. It will be interesting to see whether Boeing’s international approach to sustainment of the aircraft will follow the new USAF direction, or whether global clients, such as in the UK will want the “older” tested PBL model.

In the logistics domain, the gap between U.S. practices and those of its allies are likely to widen in the period ahead. Getting rid of PBL is significantly easier than actually delivering effective government-led sustainment efforts. The proof will be in the pudding.

***

References:

[1] See for instance: http://www.boozallen.com/media/file/performance-based-logistics-perspective.pdf

[2] Inside the Air Force, “Air Force to Manage Logistics for KC-X Tanker, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter”, January 29, 2010

———-

***Posted February 15th, 2010