As the Wall Street Journal put it, “web is new front among cold war foes.” In this article, the author, Siobha Gorman, noted that :

“Alleged attacks on Google Inc. from China redraw the battle lines between the U.S. and its former Cold War adversaries, who are now squaring off on a new front: cyberspace. In the new cyber war, the targets are U.S. companies as much as embassies or spy services, because corporations hold giant repositories of sensitive information and can be easier to crack. Companies are responding in kind, often launching their own intelligence operations to counter the spies.”

***

This is John’s first contribution to sldinfo.com: he will provide regular insights into how to shape effective con-ops in the cyber domain. John has a wide range of combat and government experience. He is a West Point graduate with warfighting experience in Vietnam. He has significant private sector experience, as well as holding various positions in government, including being Secretary, US Securities and Exchange Commission. His most recent position as Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Air Force included principal tasks, among which were standing up Cyberspace Forces and placing Precision Strike technology and Real Time Streaming Video targeting links into the hands of groundfighters in combat.

***

Cyberspace is emerging in the consciousness of defense planners, the Congress and the public as a new operational domain, like Air, Surface Sea, Undersea, Space, and Land. US Government-wide, it is a process of fits and starts, just as in the case of the emergence of the Air and Undersea Domains in the early 20th Century. As the agencies of the United States Government frame and respond to the issues regarding Cyberspace, a complex process is underway.

It is possible to list the main factors that assist in following and interpreting developments in Cyberspace. The cyber defense debate is a confusing one. This “terms of reference” overview provides a way to understand the major dynamics at play and to provide a way to navigate the policy debates for 2010. The TOR is organized around five main principles and then a list of defining factors that aid the tracking and interpretation of Cyberspace developments. The conclusion is a Notional Mission Statement for USCYBERCOM, in order to focus comment and discussion. A full Reference list follows, as a set of key documents and statements.

Facing a New “Cyber Sea” and uncharted “Cyber waters”

The Five Principles

In overview, US policymakers stand in shoes similar to those of the pioneer leaders of the 1920’s and 30’s in the air and undersea domains. Five verities apply in Cyberspace, as in any domain.

-

Principle 1

The ultimate national aim is Freedom of Cyberspace, just as in Freedom of the Seas, Freedom of the Air Domain, and Freedom of Movement in Space and within national borders on Land. This means Freedom of Ideas and of Commerce in Cyberspace.

This is based on the US Constitution, going to the “Common Defense” purpose in the Preamble and in the provisions in Article I and Article II for protecting freedom of the sea lanes – an unbounded domain similar to Cyberspace. The application of the Constitutional guidance to the Air Domain followed naturally, and so also to Cyberspace. Cyberspace is a “commons” in the full sense of the word, to be kept open and defended.

The History of US response to war threats is that the US can dominate any domain of war. In the case of Cyberspace, it was the USA that pioneered the precursors to the Internet and to earliest operations in Cyberspace. SAGE, “Semi-Automatic Ground Environment” – was built to shift command and control around nuclear targets that have been destroyed by fission or fusion attack.

The SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) System, was designed and built in the 1950s to defend against the threat of Soviet bombers attacking the continental United States (see: http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=06drBN8nlWg)

- Principle 2: In Cyberspace each of the nine Principles of War fully applies: Mass, Offensive, Simplicity, Surprise, Maneuver, Objective, Unity of Command, Security and Economy of Force.

A key action and a measure of success will be to develop, test and prove in combat a conop or conops for successfully applying each Principle.

For national defense, the professional skills of Law Enforcement, Warfighting, and Intelligence all come to bear. Since deterrence, defense, and offense in war are decisive in any domain, full awareness and consideration of the Principles of War is a key to planning and understanding. General James Cartwright USMC, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff spoke on the Principle of the Offensive: History teaches us that a purely defensive posture poses significant risks: the “Maginot Line” model of terminal defense will ultimately fail without a more aggressive offshore strategy, one that more effectively layers and integrates our cyber capabilities. If we apply the principles of warfare to the cyber domain, as we do to sea, air, and land, we realize the defense of the nation is better served by capabilities enabling us to take the fight to our adversaries, when necessary to deter actions detrimental to our interests. - Principle 3: In Cyberspace Operations require a balance of Warfighting, Law Enforcement and Intelligence effort.

In the Air, Sea and Land Domains, Law Enforcement and Warfighting are the active protections, and Intelligence carries out its core function of data-gathering and warning. In Cyberspace, due to the history of the evolution of Cyberspace doctrine from the communications and electronic surveillance fields, there has been a heavy Intelligence participation in operations.

Since Law Enforcement, Warfighting and Intelligence each involve differing professional skill sets, a balance of the three functions is vital. Where Intelligence action in Cyberspace overlaps with Warfighting and Law Enforcement, the staff and resources burden on Intelligence can be eased by shifting the Cyber functions more toward Warfighting and Law Enforcement, so that the Intelligence Community can focus most efficiently on burgeoning terrorist-tracking threats. - Principle 4: Humility is in Order: 2010 is an early stage in Cyber Warfare Evolution.

There is much we cannot know, so that it is premature to make determinations about whether or not the U.S. can dominate or deter in Cyberspace. So to speak, all nations are wading still close to shore into the new “Cyber Sea.” Nevertheless, the Mission of the U.S. Warfighter remains, by doctrine, to deter, and, if needed, fight and win swiftly with minimum casualties and cost in Cyberspace: an “Unfair Fight.” Drawn-out, “fair-fight” wars remain traps. - Principle 5: Privacy Concerns are Manageable.

The immutable requirement of the Constitution is to Provide for the Common Defense, under Article I and II. In the current political world citizen privacy is a concern that delays Cyberspace development. The mechanisms of the Constitution provide resolution, as in the case of the Air and Sea Domains, with citizen information and private sector information gathered in controlling flights and sea passage, and, from Article III, use of a special FISA court to protect citizens. Similar solutions are feasible in Cyberspace.

Wanted: A Leap of Imagination to Deter a Possible “Cyber Pearl Harbor”

The Defining Factors

Listed below are fourteen distinct defining factors susceptible to help monitor Cyberspace developments and evolution.

- Potential Foes are advanced in the domain.

They are already menacing the world and U.S. interests, as did Nazi and Japanese aircraft and submarines in the 1930’s. - The Taxonomy is new but vital, because it shapes thought and action.

XXth Century nomenclature drawing on terms like “network operations” is being displaced by taxonomy based on terms such as “cyberwar” and “cyber operations.” - A Leap of Imagination is needed to envision main war in the domain.

- Learning Takes Time and Pain.

Years and combat will transpire before the full force of Cyber Deterrence and Warfighting are well mastered, just as it took main war to reveal the full force of the air and undersea warfights. There is an “American Way of War” that is ingrained in US culture, and it tends to involve delays and then unfortunate disasters along the road of learning, such as First Bull Run, the Little Big Horn, Pearl Harbor and the Trade Towers. - Turf Battles Can Ensnare Progress.

This is part of the “American Way of War”, where legal, statutory and treaty concerns can ensnare planning and forward motion. This is the natural political process in government, and Cyberspace policy and budgeting is no exception. - Recruiting, Training, Equipping are Telltale Indicators.

Recruiting and commissioning in each of the Armed Services and Government wide is a key factor to watch and track. Congressional guidance is incomplete in the Cyberspace Organize, Train and Recruit functions. Increasingly, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees will have jurisdiction, in adjustment from the prior regime where the House and Senate Select Committees on Intelligence have by default administered much of Cyberspace policy.

Placing Cyberspace in Title 10, USC. Title 10 guidance on Cyberspace would correct a gaping lack in the statutory predicate for organizing, training and equipping in for Cyberwar. USCYBERCOM is untethered without this guidance. - New Cyber Weaponry Abounds.

Cyber technology is proliferating and needs testing, for example, software packages, links to aircraft, spacecraft, and sea vessels, and troops on the ground. - The Domains are Interdependent.

Coordinated and integrated deterrence, defense and attack among U.S. Warfighters in the U.S. military services and with Law Enforcement needs doctrine and practical experience. - Defense Retrenchment is Under Way.

There is a political spirit of retrenchment in defense spending, including efforts for a “nonaggression” treaty in Cyberspace, notwithstanding foreign peer buildup — a situation similar to the United Kingdom exactly a century ago when young Churchill grasped the undersea domain and the vulnerability of battleships. Defense atrophy may be an impending risk. - First Responders and the Commercial Structure are Vital Partners.

They work in the cyber domain just as they do in the air domain, creating a need for coordination, command and control that includes them. - Savage Major Attack is Possible.

Some planners foresee savage surprise attack as possible or even probable, a “Pearl Harbor” such as fission detonations in DC and NYC, including an Electromagnetic Pulse from the groundburst, or a separate airburst, that would disrupt or erase local Cyberspace. - Melding “old” cultures with “new” is a Challenge.

As aviators with infantry, so cyber warfighting with traditional intelligence and infantry cultures.

The extensive private sector experience with mergers and acquisitions and the long travail of melding differing cultures speaks to the difficulties inherent in combining Warfighter, Law Enforcement and Intelligence professionals to operate in Cyberspace. - December 2005 Was the Modern Turning Point in Cyber Evolution.

Since 1995 and some years before, personnel in all Services and the Intelligence agencies saw the emerging vulnerability of web sites to interruption and the risks of internet penetration. By 2000 defense planners saw the emerging idea of a new domain in the mass of evolving communications via computers and data links.

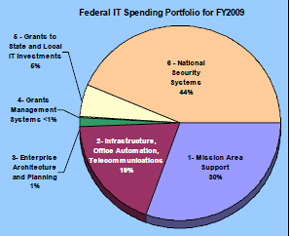

The turning point was the action of the US Air Force in December, 2005 designating the Mission of fighting and winning in Cyberspace as a formal part of the US Air Force Mission Statement. This marked the first formal elevation of the term “Cyberspace” to name the Domain, and it sharply elevated national awareness of the Domain. For example, between November 2005 and February 2006 the number of Google Hits on the term, “Cyberspace” increased more than tenfold. The action of a warfighting service to name the Domain and set the Warfighting Mission in the Domain spurred the defense community, coalesced awareness of each Military Service’s programs in the Domain, opened Defense-Wide and Government Wide Debate on Cyberspace vulnerabilities and opportunities, and led to a 73% increase in funding government wide for Cyberspace activity from 2004 to 2009, to at least $7 Billion per year.

The Russian use of Cyber Preparatory Fires in 2007 in Estonia and 2008 in Georgia and the increasing and huge predations of US intellectual property and defense information by suspected Chinese agents accelerated US Government concern, action, and funding. Privacy activists mobilized, creating drag on the pace of standing up a robust Cyber Warfighting capability.

As a matter of Taxonomy, US Government Cyber activity as a whole became termed “Cyber Security”, and the Department of Homeland Security was given US Government lead for Cyber Security. The dynamics of US Government action in Cyberspace remain fluid and continue to evolve, as with the Air and Undersea Domains in the 1920’s and 1930’s. - The Mission Statement for USCYBERCOM is a Key Indicator.

A Presidential Order or SECDEF Order and perhaps in time a Statute will presumably set the Mission. Per SECDEF’s June 23 Cyber Command Standup Memo:

Cyberspace and its associated technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to the United States and are vital to our Nation’s security, and, by extension, to all aspects of Military operations.

Yet our increasing dependency on cyberspace, alongside a growing array of cyber threats and vulnerabilities, adds a new element of risk to our national security. [emphasis added:] To address this risk effectively and to secure freedom of action in cyberspace, the Department of Defense requires a command that possesses the required technical capability and remains focused on the integration of cyberspace operations. Further this command must be capable of synchronizing warfighting effects across the global security environment as well as providing support to civil authorities and international partners.

The Mission statement not only defines core tasks and objectives; it can inspire the Cyber Command and build morale. A watered-down or obtuse mission statement telegraphs weakness and ill-resolve to potential foes and fails to inspire and mobilize focused action. The Commander will want as strong, inspirational and empowering a Mission Statement as is prudently possible.

While some observers believe that Cyber-based deterrence in Cyberspace is not possible, that view is inconsistent with freedom of action and maximum risk reduction; similarly, some observers believe that U.S. dominance in Cyberspace is neither possible nor desirable. That view is at best premature given that Cyber Warfighting is in an infant stage, with much to be learned in coming years.

In sum, then, a Notional Mission Statement follows from the Constitutional duty of providing for the Common Defense:

“The mission of USCYBERCOM is to preserve American Freedom of Cyberspace by deterring and defeating foreign cyber assault on the United States, her allies, and citizens and by aiding law enforcement, first responders and allies.”

**********

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: KEY REFERENCES LIST

1. Keith B. Alexander, “Warfighting in Cyberspace”, 2007. Strong vectoring for the Cyber Warfight. Article has primarily Warfighter, not Intelligence, perspective (http://www.military.com/forums/0,15240,143898,00.html).

2. Harry Summers, “On Strategy”, 1982. A superb statement of the Principles of War illustrated through a recent fight – Vietnam — still fresh in memory, so that the Principles are well illustrated and couched in terms applicable to Cyberwar and War in any domain. (http://www.amazon.com/Strategy-Critical-Analysis-Vietnam-War/dp/0891415637/ ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1263242130&sr=8-1).

3. William Gibson, “Neuromancer”, 1984. Shortly after authoring a short story in which he coined the term, “Cyberspace”, Gibson wrote this novel. It is a must-read for the drill of stretching the imagination to grasp the Cyberspace Domain. The novel has proved to be prescient in foretelling real-world developments. Admittedly a bit racy on the storytelling side. U.S. Gen X, Y and Z Cyber Adepts list it as must-read, and are right to do so. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuromancer).

4. Orson Scott Card, “Ender’s Game”, 1985. This is adroit fiction that assists in the intellectual stretching to imagine the Cyberspace Domain. U.S. Gen X, Y and Z Cyber Adepts list it as must-read, and are right to do so (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ender’s_Game).

5. Joint Staff Officer’s Guide, “Estimate of the Situation”, 1997 (http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/dod/docs/pub1_97/Appenf.html).

6. United States Armed Forces Order of Battle, 2008. Useful for envisioning the OB (Order of Battle) for Cyberspace Warfighting (http://www.geocities.com/Pentagon/9059/usaob.html).

7. Joint Fire Support Support Operations, 1989 (http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/fm/6-20-30/Ch3.htm).

8. “A Semantic Web Application for the Air Tasking Order”, 2005. A think-piece that assists in formulating a notional Cyber Tasking Order (http://stinet.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA463762&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf).

9. Edward M. Cook, “Selected Principles of War as They Apply to Counterdrug Operations”. The Principles of War apply in substantial degree to Law Enforcement. Warfighters deter, seek out, fix, and destroy the foe; Law Enforcers deter, and seek out, fix and bring the lawbreaker to justice (http://www.stormingmedia.us/39/3960/A396073.html).

10. Anthony McIvor, Ed. “Rethinking the Principles of War”, 2007. This work features the fresh thinking of twenty-nine leading authors from a variety of military and national security disciplines. Chapter 28 by Michael Warner, “Intelligence Transformation Past and Future” is valuable reading in applying the Principles of War to Cyberspace (http://www.amazon.com/Rethinking-Principles-War-Anthony-Ivor/dp/1591144817).

11. William A. Owens, Kenneth W. Dam, and Herbert S. Lin, editors,“Technology, Policy, Law, and Ethics Regarding U.S. Acquisition and Use of Cyberattack Capabilities”, 2009, Committee on Offensive Information Warfare, National Research Council. Current and comprehensive assessment of the Cyberspace Domain as it is currently understood (http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12651).

12. Nicholas A. Lambert, “Sir John Fisher’s Naval Revolution”, 1999. Strong similarities from 1909 to USA of 2009 – insufficient funding for defense, exhaustion of the Treasury, a kind of Anesthesia of Pacifism, apparently eroded Will to Deter and Fight; emergence of new war domains: air and undersea; Churchill grapples with the effort to envision the new domains in actual full battle in peer war (http://www.amazon.com/Fishers-Revolution-Studies-Maritime-History/dp/1570034923).

13. Andrew F. Krepinevich, “The Pentagon’s Wasting Assets”, 2009. Foreign Affairs Magazine. Points to the need to lift the veil of mystery from Cyberspace, move Cyber Warfighting into the military domain, and focus US strike on long range capabilities (http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/65150/andrew-f-krepinevich-jr/the-pentagons-wasting-assets).

14. James E. Cartwright, Statement in Ref 11, above re Cyberwar, page 3-1: “History teaches us that a purely defensive posture poses significant risks: the “Maginot Line” model of terminal defense will ultimately fail without a more aggressive offshore strategy, one that more effectively layers and integrates our cyber capabilities. If we apply the principles of warfare to the cyber domain, as we do to sea, air, and land, we realize the defense of the nation is better served by capabilities enabling us to take the fight to our adversaries, when necessary to deter actions detrimental to our interests.”

15. SECDEF Order June 23, 2009, “Establishment of a Subordinate Unfied U.S. Cyber Command Under U.S. Strategic Command for Military Cyberspace Operations.” (http://fcw.com/articles/2009/06/24/dod-launches-cyber-command.aspx).

16. Data and Charts on US Government-wide IT Spending (http://download.101com.com/pub/gcn/newspics/AgencyIT-ITsecurity-spending09.pdf; http://gcn.com/articles/2008/02/07/spending-for-it-security-gains-ground-in-09-budget.aspx); Informative 2005 Article by Michael Freeman, Scott Dynes, and Adam Golodner of Dartmouth (http://www.ists.dartmouth.edu/library/119.pdf).

17. Cost of predations on US Military Cyberspace (http://www.computerweekly.com/Articles/2009/04/09/235591/cyber-defence-for-us-military-costs-16m-a-month.htm); thorough exposition on Cyber Threat and Statement by STRATCOM Commander General Kevin Chilton about the scope of the threat (http://www.nationaljournal.com/njmagazine/cs_20080531_6948.php).

18. The power of Taxonomy (e.g. 21st Century “Cyber Operations” vs 20th Century “Network Operations” (http://www.amazon.com/Language-Thought-Action-S-I-Hayakawa/dp/0156482401/)

In the analysis below by John Wheeler, the author sorts out the nature of the cyber challenge and provides a clear focus to shaping a cyber doctrine for the United States. John Wheeler provides indeed a very helpful overview to a very confusing and conflictual problem: what is the nature of the cyber security challenge and what concepts of operations do the US and allied governments need to shape to effectively meet the latter?

———-

***Posted January 11th, 2010