New U.S. National Security Space Strategy Proposes New Partnerships

03/22/2011 – The new approach expounded in the National Security Space Strategy released by the Obama administration in early February could, if implemented, affect a number of SLD readers, including the military logistics community, industrial players, and civilian contractors, as well as anyone interested in how U.S. military space public-private partnerships are evolving. It could affect evolving allied relationships as well.

The 2009 National Defense Authorization Act directed the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) to conduct a joint and comprehensive Space Posture Review (SPR). The Review was conducted in close consultation with other agencies and partners. OSD and ODNI waited until after the release of the more comprehensive U.S. National Space Policy (NSP) in June 2010, which reversed several positions advocated in the 2006 version, before finalizing and releasing the new National Security Space Strategy (NSSS), which provides the overarching guidance requested by Congress.

In addition to the NSP, the NSSS draws guidance from the White House National Security Strategy (NSS), the Department of Defense’s Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), and the Intelligence Community’s National Intelligence Strategy. Only an unclassified summary was released on February 4. The classified version, which was sent to Congress the day before, is four pages longer. According to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy Gregory Schulte, who briefed the media on the day of the public release, “there are no surprises in the classified version.” The NSSS produced in the George W. Bush administration was never publicly released.The NSSS stresses how outer space is becoming ever more important for U.S. national interests, and is crucial for U.S. military operations and intelligence collection.

The Pentagon uses space-based assets for communications, reconnaissance, navigation, targeting, and other core military activities, while satellites provide vital information to the U.S. intelligence community. These assets are essential for important U.S. national security missions including conducting combat operations, verifying arms control agreements, analyzing foreign defense developments, and monitoring long-term environmental conditions. The Pentagon’s commercial, civil, and foreign partners also rely on unfettered access to space for economic, scientific, and international missions that benefit the United States. The Pentagon relies on commercial satellites for much of its communications and imagery, especially in Afghanistan.

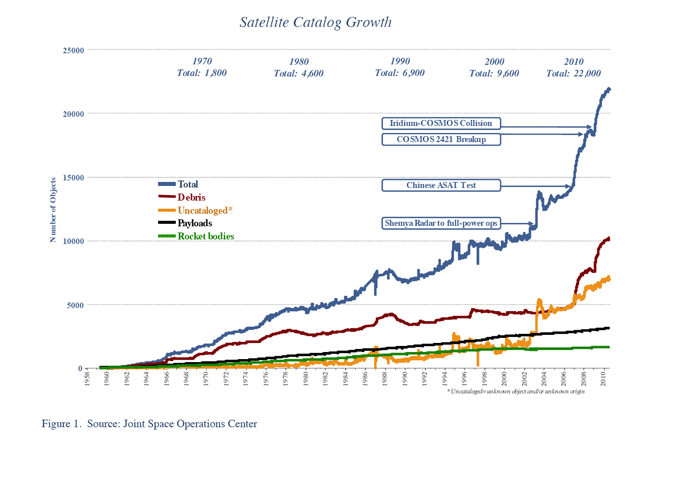

Photo Credit: Growth in Global Space Sat Traffic, NSSS, page 1

Photo Credit: Growth in Global Space Sat Traffic, NSSS, page 1

The NSSS directs major changes in how the U.S. government approaches several space issues. “The National Security Space Strategy represents a significant departure from past practice,” Robert Gates announced in the public release. “It is a pragmatic approach to maintain the advantages we derive from space while confronting the new challenges we face.” SLD readers will be most interested in how the NSSS aims to transform U.S. space-related acquisition and export policies as well as renewed the U.S space industrial base.In terms of space acquisition reform, the NSSS envisages a robust, competitive, flexible, and healthy space industrial base that delivers reliable space capabilities on time and on budget. In various briefings around Washington, U.S. officials have agreed with various SLD critiques that the current practice of pursuing inconsistent acquisition and production rates and long development cycles have weakened the U.S. space industrial base.

The decrease in specialized suppliers could deny the U.S. access to critical technologies, make the U.S. dependent on foreign sources, and weak U.S. innovative potential. DoD and IC satellites that have been developed in the past decade have cost billions more and been delayed years in terms of delivery.Frequent changes in government requirements, such as to introduce new technologies or to decrease volume of purchases, frequently increase costs and delay schedules. These problems were epitomized by the high-profile cancellation in 2009 of the Air Force’s planned Transformational Satellites (TSAT), which was designed to revolutionize satellite communications, due to their high costs and technical delays.The NSS proposes various solutions to stabilize acquisition and requirements-generation processes. The Defense Department will increase its own space acquisition workforce by hiring 9,000 new employees and converting 11,000 contractors to federal service in the next five years. The intent is to strengthen in-house expertise in cost estimation, systems engineering, and program management.

The NSS will also employ a more holistic view of the space industrial base by expanding reliance on commercial and foreign suppliers. For example, U.S.-based DigitalGlobe and GeoEye each have contracts under the EnhancedView program to provide remote-sensing data to the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.In addition, the U.S. government is considering paying commercial satellite operators to host government payloads. Using private launchers gives the government flexibility to deploy a payload on a satellite close to launch. DoD leaders also seek to increase transparency between government and industry through more dialogue and meetings. This can open up a whole new approach to dealing with entities such as Space X or Arianespace.

The NSS also states that the Defense Department will improve the way its sets requirements by adding configuration steering boards to help stabilize requirements early on in the acquisition cycle, relying more on independent cost estimates for developing programs and fixed-price contracts for programs in execution phase, and imposing discipline by canceling programs that are no longer needed, will cost too much, or are not working technically.Other space acquisition reforms will include better managing investments across portfolios to ensure the industrial base can sustain critical technologies and skills.

In addition, the Defense Department will shorten development cycles to minimize delays, cut cost growth, and enable more rapid technology maturation, innovation, and exploitation. Furthermore, DoD will synchronize the planning, programming, and execution of major space acquisition programs with other DoD and IC processes. One major change will be that the Defense Department will pursue transformational capabilities only when necessary. The U.S. government will complement the development of satellites with revolutionary technology with smaller, less expensive satellites that can be developed and launched more rapidly. They will only provide incremental capability improvements, but they will avoid the high expense and high risks of revolutionary systems that can often fail (e.g., TSAT).

This new approach is reflected in the administration’s new Evolutionary Acquisition for Space Efficiency (EASE) Initiative. This initiative will rely on block rather than unique buys, fixed-price rather than cost-plus contracts (which require the government to pay for any overruns), and technology infusions only at regularly scheduled intervals.The resulting more predicable demand, with multiple purchases of the same satellites, should produce more stable and sustained production lines and product workforce that generates economic efficiencies. EASE will likely first apply to the Advanced Extremely High Frequency satellites. DoD will continue to rely mostly on cost-plus contracts for immature and innovative programs where the costs are less predictable. The Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles (EELV) program is becoming another early test of the new approach. DoD is increasing spending on the EELV program to ensure a stable block buy.

The Obama administration export reform program aims to move in two directions designed to enhance the U.S. industrial base while protecting unique U.S. advantages. The problem is that current approach toward space exports is harming U.S. space exporters while not greatly impeding states of concern from acquiring sensitive technologies. The administration wants to guard state-of-the-art as opposed to state-of-the-world technologies.The reforms aims to construct higher fences around most sensitive technologies, but allow easier export of items outside the fences. In making export control decisions, the administration will consider whether commercial articles are the product of unique capabilities that cannot be obtained in other ways, the actual risk of U.S. exported equipment being someday used against the United States or its allies, the greater control the United States gains from selling the technology itself, how improving allies’ capabilities helps them contribute to coalition operations, and the damage to U.S. industrial base if sub-tier suppliers go out of business by not being able to export their products.

Another change is to restore the health of the U.S. “space cadre” as well as U.S. space-related science and technology. This will entail enhancing recruiting, retention, and training policies designed to develop current and future national security space professionals in the military, intelligence, civilian, and contractor components of the work force.In addition, the administration proposes to support science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education initiatives designed to produce skills and capabilities need by future space professionals. The government will also encourage the space community to improve how it incorporates new space-related research and technology, including those developed outside the United States, into U.S. space systems.

OSD and ODNI will now apply this new general strategic guidance, which seeks to guide U.S. space polices for the next decade, to specific planning, programming, acquisition, doctrinal, and operational decisions. The Deputy Secretary of Defense revalidated the role of the DoD Executive Agent (EA), currently Secretary of the Air Force Michael B. Donley, for Space to integrate and assess the overall DoD space program and facilitate increased cooperation with the Intelligence Community The Deputy Secretary of Defense established a Defense Space Council, chaired by the EA, to serve as the principal advisory forum overseeing NSSS implementation. He also serves to coordinate DoD policies toward agency, industrial, and foreign partners. The NSSS has some 30 action items for all agencies, and DoD has a leadership or major stake in many of them.

The Council will align requirements, acquisition, and budget planning and execution with strategy and policy. The Council’s initial priority has been to streamline the many DoD and national security space committees, boards, and councils.The FY 2012 DoD budget (which also funds IC space programs) contains only initial steps toward implementing the new strategy. DoD and ODNI will use this year to make more comprehensive changes in FY 2013 and beyond. In the words of the Secretary of Defense, “The strategy provides a basis to update defense plans and programs and make the hard choices that will be required to implement the strategy. We look forward to working closely with Congress, industry, and allies to implement this new strategy for space.”