2013-02-11 Unfortunately, the debate about the littoral combat ship, and the confusion of building a fairly limited ship with disruptive change, has obscured the real transformation at sea.

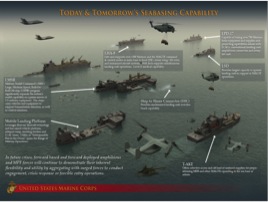

The dynamics of change affecting the seabase are truly significant.

The ARG-MEU is being transformed into an expeditionary strike group.

With the addition of new aviation assets, the F-35B and the Osprey, the whole impact of a seabase is being transformed.

With the addition of a new flagship for the seabased force – the USS America – the ability to shape significant flexibility is evolving as well.

And the supply side of the seabase is undergoing significant change as well.

The new T-AKE ships for Maritime Prepositioning Squadrons are bringing new capabilities to the seabase, notably an ability to identify pallet loads onboard and deliver to where they are needed. Hitherfore, the supplies on prepositioning ships were loaded in 20 foot containers which would take days of sorting through to make them ready to support a combat force.

And now a new “floating” port at sea is being added to the mix. To be christened in early March, the USNS Montford Point will bring a whole new capability to the fleet and to support of the seabase enabling the USN-USMC team.

The ship is named in honor of African American Marine Corps recruits who trained at Montford Point Camp, North Carolina, from 1942 to 1949.

And at a price equivalent to an LCS, this “floating” port is a bargain.

Unfortunately, current plans call for only two, with the second to be only deployable after several days necessary to mobilize.

In preparation for the christening of the USNS Montford Point at the NASSCO shipyard in March 2013, Second Line of Defense sat down with Jim Strock, a widely recognized expert on seabasing for the USMC.

He is the Director Seabasing Integration Division and members of his Connectors and Doctrine (C&D) Branch at the Marine Corps Combat Development Command MCCDC), Quantico.

(For an overview on the evolving sea base see the following document as well:

Annual_Report_Dec_2012_250_Print_reduced_size)

SLD: The ship, which we will see in March, is not the same as originally conceived. Could you describe the shift from original concept to the ship that is in the water?

Strock: The original Mobile Landing Platform was an entirely different ship under the MPF Future Construct and there was a complete capabilities document that was written.

There was a ship design team put together. We were in the throes of working the design when in the summer of 2009, the Department of the Navy made a conscious institutional decision to no longer pursue the MPF Future Construct but rather seek ways to enhance our current Maritime Prepositioning Ships program. A Tiger team was formed and came back with recommendations, which led to the current ship design.

When the NAVSEA PEO Ships came forward with a revised Mobile Landing Platform, that revised platform was downscaled significantly, but it preserved two essential seabasing capabilities.

The two essential capabilities that we wanted upfront was the ability to skin-to-skin marry to an LMSR at-sea, sea-state 3, come along side, tie those two ships together and then be able to move heavy rolling stock equipment up to and including tanks from the LMSR to the MLP. Secondly, the MLP would then be able to interface with LCACs to maneuver equipment ashore. It has been designed to provide for at-sea transfer of rolling stock at no less than sea-state 3.

In effect, it is a pier in the ocean.

One could selectively offload from the LMSR to the MLP, and/or interface with LCACs. The LCACs would have to be provided by amphibious ships. The MLP is not designed to husband its own LCACs. One is not going to husband them or maintain them onboard the MLP.

In other words, the MLP, even though it’s part of a prepositioning squadron, does not preposition any equipment itself.

SLD: The cost containment of the program is built around the ability to leverage a commercial hull and construction techniques. Could you explain the approach?

Strock: The MLP hull form is based on the Alaska-class crude oil carrier that NASSCO had been building for BP. They cut the center section out, installed ballast tanks so you could put nine feet of water over the main deck so you could float on and float off the raised vehicle deck and the LCAC lanes and such. It thereby can be characterized as a float on/float off vessel.

SLD: How does the MLP fit in to the prepositioning squadron?

Strock: In 2009, we went to the Undersecretary and we said, “The MPS squadrons already have LMSRs, which we got from TRANSCOM to replace the aging Mærsk-class ships that we had acquired in the early ’80s.

We asked the Under to take the T-AKEs, which were originally three of those were bought from the MPF Future program, and we asked the Under to reassign those to MPS.

One T-AKE per squadron will take roughly 20 percent of supplies that were previously kept in 20-foot containers and you would re-stow at the pallet level for selective offload of supplies.

So between the MLP and LMSR combination and the T-AKE capabilities, you can now within each pre positioning squadron get to a certain percentage of the rolling stock and the supplies for at-sea selective offload.

You could never do that before with MPS ships because rolling stock was densely packed and the supplies were stuffed in containers and the only way to get at the supplies was to send the containers ashore and un-stuff them.

Now back to a discussion of the role of the MLP in this effort.

LMSRs already part of the maritime prepositioning ships squadrons. They’d been around for years. We simply acquired the operating rights for some of them from TRANSCOM, and the T-AKEs for MPF Future were funded in 2009/2010 so they were already bought and paid for and were part of a 14-ship run.

So we had the T-AKE piece. We had the LMSRs.

The missing link was the MLP.

In August of 2009, Mr. Art Divens, a senior executive at NAVSEA, came forward during the brief to the Under with the revised Mobile Landing Platform idea. He said we think NASSCO can build this based on the Alaska-class crude carrier design.

The Under agreed, and plans were initiated to pursue that design.

In the FY11 Navy shipbuilding plan, the Navy funded one of them. In the resource management decision signed off by Secretary Gates in March of 2010 for FY11, the Sec Def RMD 700 stipulated that the Navy would buy a total of three of these MLPs and OSD provided an extra $1 billion to do so.

The first twop MLP’s were funded in FY11. Now since then, we’ve come down to two squadrons, so at this juncture for prepositioning purposes, MLP’s 1 and 2 are crucial.

MLP-1 is getting christened in March and we expect delivery later in 2013. The keel was laid for MLP-2 in December, and it will be named after Senator Glenn.

After she’s delivered, MLP-1 will go through probably a year’s worth of post delivery shakedowns and so on. And in the meantime, the Marines, in concert with the Navy are holding various working groups and meetings. We’re developing tactics, techniques, procedures, operational handbooks, working with the assault craft units, LCAC operators, particularly the experimental LCAC crew down in Panama City, Florida, who did all of the original 90-degree approach and departure testing and demonstrations on a MLP surrogate, the motor vessel Mighty Servant, to get it in all place.

To recap: the MLP is currently designed and built. We’ll do skin-to-skin marriage to an LMSR, at-sea transfer of rolling stock from the LMSR to the MLP using the LMSR’s existing side door and the LMSR’s organic ramp and then interface them with LCACs. In sea state-3 conditions, we’ll be able to transfer vehicles, up to and including M1 tanks, from LMSRs to MLPs to LCACs.

But this will just be the beginning. As we begin to employ these new capabilities, there will be an evolution, if not revolution, of tasks and working relationships with ship and aviation assets which can be rolled out.

SLD: Could you give an example of some of the ramp up possibilities for the MLP?

Strock: For example, one could potentially put a berthing barge on the MLP. The Navy’s had berthing barges for years in the shipyards.

When you have to get the crew off a ship when she’s in dry dock, you put them in a floating hotel. It’s called a “Berthing Barge.”

You could design a self-contained berthing barge to house 200, maybe 300 people, with classrooms, showers, head facilities, dining hall facilities.

The MLP’s have space and weight to potentially accommodates those additional capabilities, just on the basic design of the ship.

SLD: In effect, the MLP is part of the evolution of seabasing that when considered with the transformation of aviation assets can allow for some significant change in capabilities and operations.

Could you address this possibility?

Strock: If you look at my brief towards the end where at the “Seabasing What’s Next” you can see some of the possibilities of change.

We’ve already been down to talk to the Army Chief of Transportation at Fort Lee, Brigadier General Stephen E. Farmen. The Army has host of ocean going watercraft. We need to test if Army LCUs or Army Logistic Support Vessels could do a 90-degree ramp down marriage to the MLP for possible equipment transfer.

We need to see if the Navy’s landing craft utility, the 1610 Class LCUs, could they do ramp down, what we call athwart- ship, 90-degree approach, on the MLP for at-sea transfer.

We need to examine: Can you bring a joint high speed vessel alongside the MLP, slew its ramp 45 degrees and do at-sea transfer between JHSV and MLP?

And the combinations become endless, so you look at all of the various Army watercraft, and as you look at other military sealift command assets, and all the various multinational capabilities.

The lance corporals and the gunnery sergeants are going to figure a lot of this out. The petty officers, the gunnery sergeants, the seamen, the lance corporals, these are smart people. They’re going to find ways to make stuff work together that we haven’t even thought about at the start of the effort.

SLD: Where will the ships be home ported?

Strock: The first one will be going to go to Diego Garcia. The second one, due to funding constraints, will be put it into reduced operating status five.

This means it can be available for tasking in five days. This means that within five days you can get it underway. If you put it in reduced operating status, you have a skeletal crew onboard, just to keep it warm.

But the beauty of the MLP is since you don’t carry any prepositioned equipment, in order to activate the ship in five days, that essentially is sending a shuttle bus to the Mariner’s union hall to pick up the rest of the crew and get her underway.

SLD: Could you identify how it might be used in a crisis?

Strock: Once that thing gets delivered, it would be available for crisis response. If you’ve got another Tsunami where shore infrastructure gets wiped out, an LMSR with an MLP, coupled with amphibious ship LCACs, and a T-AKE coupled with amphibious force V22s, you can operate from the seabase and selectively send supplies and equipment ashore without having to offload all of your prepositioning stocks in some arrival and assembly area and sort them out.

With what we call the “Seabasing-enabled MPS Squadron” you can selectively offload and reinforce and supportfrom the seabase long before you take the other densely packed ships and send those ships pier side for a traditional afloat prepositioning offload and the arrival and assembly process.