2015-09-23 By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

Recently, General “Hawk” Carlisle underscored that the USAF is already engaged in reshaping the force to execute fifth generation warfare.

It is important to look at the impact of the F-22 operations on the total force. We do not wish, nor do the allies wish to send aircraft into a contested areas, without the presence of the F-22.

It’s not just that the F-22s are so good, it’s that they make every other plane better. They change the dynamic with respect to what the other airplanes are able to do because of what they can do with regard to speed, range, and flexibility.

It’s their stealth quality. It’s their sensor fusion. It’s their deep penetration capability. It is the situational awareness they provide for the entire fleet which raises the level of the entire combat fleet to make everybody better.

He argued that rather than thinking in terms of the integration of fourth with fifth generation aircraft, it is much more accurate to focus upon the concepts of operations being shaped by fifth generation aircraft, notably with the coming of the 5th generation fleet of F-35s.

It’s the way we train the airman and the crews.

It’s the scenarios we put them through.

It’s the Red Flags and the integration phase of weapon school.

What we teach right now is fifth generation con-ops. That includes the Raptors and what they bring to the fight, and the F-35s and what they bring to the fight, and what the cyber systems bring to the fight.

How do you bring space into that environment?

How does C2 operate inside of an information flow that is inside of anything the adversary can do?

How do you put the C2 at the point that it can execute at a rate and with information superiority that is far better greater than an adversary can react to?

And then it’s the way we train our airmen to think in fifth generation terms, rather than just flying a new platform.

And Carlisle also highlighted the key role which a sister Air Force was playing in the rethinking effort, namely the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

Here the RAAF has put in motion its Plan Jericho whereby shifting to a fifth generation warfighting approach was the strategic objective, or the shaping of a transformational force built around force integration informed and led by their next wave of new platforms, the F-35s.

What the Aussies have in mind is con-ops design driven innovation.

It is enabled by new platforms and new technologies but such capabilities are necessary but not sufficient conditions for transformation.

Cultural change is envisaged in which the force becomes much more interactive within force packages which can be ground-air-maritime or air-ground-maritime or maritime-air ground.

Successful fighting forces have periods of tremendous innovation sometimes in combat.

The Battle of Britain is one such example.

Another example has been seen by the creation of Navy’s Top Gun, USAF Red Flag, and the USMC creation of MAWTS –Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron all coming together, for example, in the very successful Desert Storm Air Campaign.

It requires courage in peacetime to have very realistic training situations because combat aviation even in peacetime tested to the edge of the envelope is inherently dangerous.

And once a shooting war breaks out the test can be life and death for a nation.

Planning in peacetime for innovation by design and executing it is a crucial element for combat success.

And here power needs to be given to the professionals to shape a way ahead, rather than overwhelm them with testers, critics, and practitioners of the past.

As one senior Air Force officer noted recently, “If it was up to Secretary Gates, we would still be flying P-51s.”

Another good example is a highly politicized process whereby the USAF did not acquire the tanker they wanted; and were forced down a path of neither receiving a new tanker, nor the tanker they had selected by an “acquisition” process which clearly did not optimize the warfighter’s approach to innovation.

And as the USAF decides how to proceed with a long range strike/ISR asset which historically have called a bomber, will this happen yet again?

The warfighters have a good idea of why they want to add this capability to the mix of evolving 21st century operations.

Indeed, they have had a good idea for some time, but will a greek chorus of critics, and practitioners prevail against the shift to 21st century concepts of operations?

As early as an 2008 interview with Doug Barrie, then with Aviation Week, in Paris, then Secretary of the Air Force Mike Wynne laid out the appraoch of a bomber which reinforced and interacted with the F-22 and F-35 in shaping a fifth generation led warfare innovation approach.

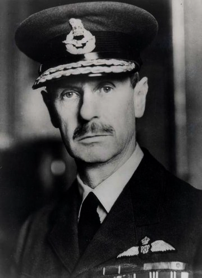

Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Caswell Tremenheere Dowding GCB GCVO CMG ADC RAF

An example of con-ops driven innovation was seen in the RAF leadership preparing for the Battle of Britain.

Air Marshal Dowding’s vision saved Britain but generated many enemies, including Prime Minister Churchill.

Just like all military technology is relative against a reactive enemy the flexibility of leaders and adaptability of Aircrews is a critical component of success in combat.

Flexibility refers to the capacity and willingness of leaders to adjust tactics in the face of a dynamic war and an adaptive skills of aircrews in understanding the combat practical use of ever evolving technology to readily adapt to the required changes.

Air Marshall Dowding was such a leader and the RAF fighter pilots were such aviators.

As Churchill saw a Gathering Storm before WW II broke out Dowding developed what he believed what be a concept of operations for the defense of Britain and then looked at the bits of technology which could be forged into that con-ops.

The fighters by themselves would not succeed; as the British fighters chewed up on the continent in the defense of France demonstrated when facing the Luftwaffe. While the courage, skill and heroism of the RAF fighters in the Battle of Britain is not to be doubted, it was the context within which they operated which generated the conditions for their success.

Michael Korda in his book With Wings Like Eagles: A History of the Battle of Britain (Harper Collins, 2009) provided a very clear picture of how Air Marshal Dowding addressed shaping a con-ops driven design within which he sought out the pieces of kit and capabilities which were needed to fill out the air defense capability he believed was necessary for mission success.

And all of this was a few years BEFORE the Nazis had seized continental Europe and then were able to use air bases much closer to Britain to generate Luftwaffe strikes on Britain.

What Korda makes clear is that the Germans were pursuing a modified version of World War I concepts of operations for their Air Force.

Fighters continued to think in dog fight terms, and the role of the Luftwaffe was largely defined as flying artillery in support of the German ground forces.

Even when bombers were pushed to the front of the strike force to attack Britain, the fighters role was to accompany the bombers and to attack other fighters, not to engage in destruction of the three dimensional system which Dowding led Britain to build to enable a British victory in the Battle of Britain.

As Korda put it with regard to the Luftwaffe:

Though nobody was about to bring it to Goring’s attention, the Luftwaffe, in fact, had not been built with this kind of task in mind.

Its successes in Spain, Poland, Norway and the attack in France had been won against weaker air forces or none, and with the Luftwaffe acting in support of the German army.

In the role of flying artillery, rather than as a long-range strategic weapon in its own right (page 13).”

The three dimensional system of fighters, radar, ground enabled C2 for the fighters came together just in time to defeat the Luftwaffe.

But it was a close run thing, and the conception of the three-dimensional space necessary to execute air defense was a clear vision but with concrete elements put together in the mid-to-late 1930s.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding was the architect of the approach which would defeat the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. He is most remembered for his unwelcome task of telling Prime Minister Churchill that no more fighters go to France to get destroyed in a losing cause; rather, they needed to be husbanded for the coming conflict, which would later be known as the Battle of Britain.

What Dowding understood, and the politicians did not, was that the con-ops shaped by design was crucial to mission success; and the fighters were the tip of the sword, not just silver bullets to be chewed up in fighter versus fighter battles.

Those fighters would be needed to kill bombers, primarily, and fighters, and they would operate from British soil and operate within a very clear strategic context, one which brought together elements of new technologies, and new was of operating which had not yet been tested in battle.

According to Korda, the three dimensional approach of Dowding was the key to understanding the concept of operations.

He had in his head (as of the mid-1930s) an airman’s three dimensional sense of how to fight a battle in the sky over southern England, and he understood that it would involve combining the newest and most radical scientific ideas about radio direction finding on a grand scale with the latest kinds of radio communications equipment and a totally new breed of fighter airplane into an efficient, tightly controlled, well-led organization linking fighters, antiaircraft guns, and ground observers into a single unite involving thousands of people and technology which did not has yet exist, pp. 16-17.

There were several key building blocks, which had to be brought together to shape an effective con-ops:

(1) The eight-gun Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire;

(2) The controlling “brain” of Fighter Command;

(3) Centralized Fighter Control;

(4) The Operations Room at Fighter Command Headquarters which was in constant communication with the radar plotters and fighter squadrons via which the battle could be systematically observed, controlled and led.

And to succeed, the con-ops would require training players in the system to work differently.

Pilots would have to shift from the tradition of aerial lone wolfsmanship and learn to be told where to fly and what to do over the radio by the ground controllers.

And this task would require a key cultural change, foreseen by the con-ops, and thereby prioritized as a key task.

Dowding had already guessed that the only way to provide the number of people who would be needed to transmit the endless flow of information from the radar stations to Fighter Command’s Operations Room and from there ‘filtered’ to the operations room of each group, and on from there to the squadrons and the pilots in the air, would be to employ large numbers of young women.

Maintenance units were aghast at the new tasks the ground crews would have to learn and the sheeer quantity of unfamiliar new tools and spare parts they would have to deal with, (p. 35).

Not only would an operations room be built at the HQ of Fighter Command, but an underground operations room would be built in advance of the Battle of Britain, for Dowding was concerned that the RAF would need to have continuity of C2 to succeed.

The centrality of the world’s first C2 facilities was not envisaged by any other global power of the time.

“Dowding had a good picture in his mind of the battle to come, and what it would take to win. Fighter Command Headquarters, he had already determined, would not just control the fighter squadrons; it would have to control the entire battle,” (page 37.)

As the C2 system was built out, Dowding was concerned to have the training in place whereby the various players had confidence in the system.

And this was built into the system by the engagement of fighter pilots with the ground controllers and the C2 system over all.

An innovation that Dowding quickly introduced was to place experienced fighter pilots in the filter Room for a tour of duty alongside the filterers, so the pilots would gain confidence in the system (which they could then spread when they returned to their squadrons) and also so they could explain to the filterers what the pilots could and could not do, and what they needed to know, the objective being that the fighter pilots must have absolute trust in the instructions they received from the ground, even if the voice was that of a young woman who had never been up in an airplane in her life, (page. 46).

And Dowding understood the importance of the joint element to mission success as well and built that into the C2 process.

Above the filterers was built a ‘gallery’ where the whole table could be observed rom above by the officers charged with warning each Fighter Group of the situation as it developed on the board below, as well as by the naval liaison officer, a senior Royal Artillery officer with a direct line to the headquarters of the antiaircraft gunners and searchlight operators and officers linked by direct lines to the Observor Corps, the police, the fire services, and those in charge of sounding the air-raid alarms, (p.45).

Shaping a 21st century concepts of operations requires a shift as profound as envisaged by Dowding for his day.

As the Aussies correctly assume, simply introducing F-35s into business as usual without reshaping their overall approach will not make a great deal of sense.

It is about training and shaping the way ahead for the 21st century world, and not simply doing platform replacement for an approach which no longer makes sense in the future, or now for that matter.

Editor’s Note: An audio interview done with Air Marshal Dowding in 1968 when he was 86 shows clearly the intellectual power of the man and his personality.

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding covers a wide range of major historical issues in this interview about the Battle of Britain. We hear about his efforts to persuade Winston Churchill not to send any more pilots and planes on operations over France after 3 June as it would leave Britain too vulnerable to air attack at home.

He also discusses the importance of radar and aircraft developments and looks at why Hitler changed tack and decided to stop bombing British aerodromes and aim for London instead.

In reply to the question ‘Would you have done anything differently?’ he ends with a comment perfectly answering that type of question:

If my aunt had balls, she’d be my uncle!

The link above is to a cleaner version of the recording and is recommended, but the you tube link provides much of it with decent clarity but obscures the response to the final quesiton which is really a pity.

The best defence of the country is the fear of the fighter. If we are strong in fighters we should probably never be attacked in force. If we are moderately strong we shall probably be attacked and the attacks will gradually be bought to a standstill. . . . If we are weak in fighter strength, the attacks will not be bought to a standstill and the productive capacity of the country will be virtually destroyed.

— Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding

Editor’s Note: And to make it abundantly clear the F-35 is not a replacement for any particular airplane; it is a whole different way of doing things as a multi-tasking aircraft, rather than a multi-mission aircraft.

But the redesign does not stop by simply introducing F-35s into the mix; it is about reshaping the whole approach to air combat, which “Hawk” Carlisle described in his interview.

As one RAF officer involved with the F-35 and Typhoon transition has put it:

‘Mission Simultaneity’ is the way we are describing it and the RAF uses this description already in the next wave of Air Power doctrine.

And it is about what is called by some the integration of 4th and 5th generation assets, and what that means is that the air assets which will characterized the air combat forces for the next thirty years, the F-35s, the F-22s, the Eurofighters, the Rafales, the latest build F-15s,, F-16s and Super Hornets, and Gripens will sort out how to work together to shape an effective fighting force to protect the US and its allies strategic interests.

A key is to understand that the modernization of the non-fifth generation fighters will be driven in large part by their evolving role shaped within the shaping function of fifth generation warfare.

And part of the shaping of new con-ops by design will be to highlight what a fifth generation fleet will do by itself, or put another way, there are very unique capabilities which an integrated fifth generation force can deliver and which a mixed fleet can not.

Air dominance and shaping the combat effects one can deliver with airpower will combine that capability with what an effectively integrated air combat force can deliver, which will include the most dynamic and effectively modernized Eurofighters, Rafales, the latest build F-15s,, F-16s and Super Hornets, and Gripens.