2010-06-23 By Robbin Laird

(rf*@*****fo.com)

The Northwest Passage: A Dream To Come True?

As the Arctic becomes altered by climate change, three key elements are re-shaping global dynamics.

- First, the melting Arctic is creating new transit routes so that past dreams like the Northwest Passage are becoming possible. Instead of the longer, more traditional transoceanic transit routes, east-west routes will open up through the Arctic.

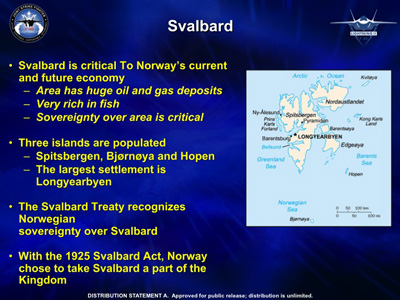

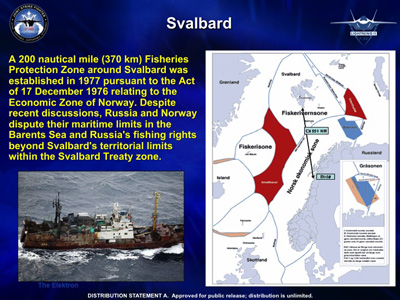

- Second, the melting Arctic is opening up raw materials to exploitation, notably oil and gas. At the same time, climate change has made the Artic environment very fragile, so that it is necessary to effectively and delicately manage the technical aspect of oil and gas extraction.

- Third, melting ice will alter the flow of water in the region, and, more importantly, alter where fish travel. Enhanced management of the fisheries will be a core challenge for countries in the Arctic Circle.

This map shows potential routes of the Nortwest

Passage and Russia’s Northern Sea Route.

Though the Northwest Passage is currently iced over,

analysts think global warming might reduce the ice

and make passage a viable shipping route in 30 or 40 years.

Credit: Arik Hesseladahl, “Wrangling over Arctic Territorial Claims,”

Business Week (January 28, 2009)

A Five-Party Management

Five states with legal claim to the Arctic will directly manage these challenges, namely, Denmark/Greenland, Norway, the United States, Canada, and Russia. The outcome of this management process will affect the core strategic interests of the entire world, including the major Asian and European powers.

The transit routes affect the conveyer belt of trade and commerce worldwide, from Asia to America to Europe, as well as the availability of oil and gas from fields closer in proximity than the Middle East.

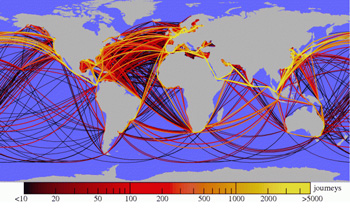

“Scientists have come up with the first comprehensive map

of global shipping routes based on actual itineraries.

The team pieced together a year’s worth of travel itineraries

from 16,693 cargo ships using data from LLoyd’s Register Fairplay

and the Automatic Identification System,

which tracks vessels using a VHF receiver and GPS.”

Credit: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/01/global-shipping-map/

- Northern European states may be able to accrue wealth and strategic advantage for themselves. At the same time, interaction of the larger European states, such as France and Germany, with the new oil rich states will significantly affect intra-European relationships, including the future of the Euro. Denmark and Norway could well have a different view of Russian behavior in the Arctic than the Germans. Indeed, differences over the management of the relationship with Russia could become a central flashpoint in the evolution of the European Union as the Arctic opens up.

- Canada’s role as an Arctic power could overshadow its other global interests. Canada has scarce dollars to invest in its defense budget, including the air and naval assets most important to managing its Arctic interests. Investments in protecting its Arctic interests could dominate the defense budget causing a decrease in spending on ground forces that are necessary to participate in global peacekeeping. Canada has real strategic interests in the Arctic, which any governing party would likely not ignore.

- For the United States, the Arctic should be a central strategic issue, but currently it is not of paramount interest. Ground operations in Iraq and Afghanistan take precedence. However, the continued inability of the US to fund new ships and aircraft for the US Air Force, Navy, and Coast Guard remains very important when focusing on the future strategic impact of the Arctic. At present, eco-preservation of the Arctic is more prevalent than any interest in the strategic impact of new transit routes and strategic commodities. Polar bears are important, but not really pawns in global geo-politics.

- Meanwhile Russia sees the Arctic as an added jewel in its crown of commodity ownership. The Russians have struggled throughout their history to translate their mineral and energy riches into sustained economic growth and development. The Arctic will once again give the Russians a chance to do this. But even without an effective investment policy, the Russians will become king makers in shaping global energy politics. Certainly, their leverage over Europe will increase.

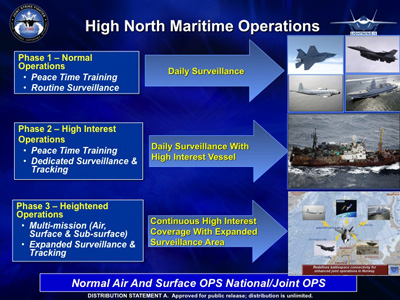

The Need For a 21st Century Air and Naval Integration Approach

The Norwegian view is shared among the Northern European states as they seek to shape a strategy to deal with the Arctic and their Russian neighbor.[4] States will re-enforce their maritime assets to manage their strategic interests in the Arctic. On the one hand, this will clearly require new ships able to operate in the period of transition in the Arctic. To quote Jane’s Navy International, the new Arctic situation creates simultaneously “opportunities and threats.”[5] On the other hand, new air and space assets are required to monitor activity, to provide ISR in the region, and to support actions as needed.

With a 21st century approach to air and naval integration, it is clearly possible to combine air and surface assets into joint operations to monitor, protect, and act as required. Now with multi-mission systems such as the F-35, F-22, and Aegis, the integration of these systems carries with it simultaneous capability to perform defense, security, ISR, or strike functions.

An “F-35-Enabled Arctic Task Force” As Part of the Puzzle?

Lockheed Martin has provided a briefing that lays out how the F-35 as a “flying combat system” working with surface assets can provide for Arctic security missions for Norway. The key really is the ability to integrate an aircraft with an on-board database of intelligence and to be able to distribute this intelligence to other elements of an Arctic “task force” to protect Norwegian interest.

The slides below lay out a notional area of interest to protect from a Norwegian point of view.

These areas of interest will require Norwegian investments over the next thirty years in capabilities to shape and protect their engagement. Norway could stovepipe the acquisition of key assets with little regard to the integration of those assets, and could do so in virtual isolation from its allies. Alternatively, Norway could have significant integration among the assets it acquires with maximum interoperability with its allies, notably with its Arctic allies. In this light, the F-35 could become an important piece for solving the co-opetition puzzle.

The graphic below identifies the different operations, which could be pursued sequentially or simultaneously by an F-35 enabled Arctic “task force.” The advantage of the F-35 is that with a small number of aircraft able to integrate across the maritime and air spectrum, the “task force” could be small indeed.

In any case, nations will acquire new capabilities to deal with the ambigious Arctic future. Comments made by one Arctic expert as quoted by Jane’s Navy International (JNI) provide a good characterization of the fluidity of the evolving Arctic situation: “Arctic expert Dr Rob Huebert, associate director of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary, says that the main challenge until recently was getting people to take Arctic issues seriously. “Now the problem is trying to define the threat,” he says. The main concern is uncertainty, but he believes that, within this context, there are three variables: climate change, resource potential and changing geo-political reality. What makes the situation more complicated is that analysts are unable to ascertain how the three variables will interact. “Under one scenario, climate change and resource development [will make] northern resources more accessible, but when you start developing those resources, you add to climate change,” says Huebert. “The Russians are rebuilding their military capabilities through their petro dollars, and guess where their future petro dollars are coming from? The North.” He adds: “My feeling is that we’re in for a really complicated situation and if you get people doing dumb things, it can get real ugly, real fast, because it’s the interface of the politics that gets things out of control.”[6]

[1] “Guardians of the North: Norway Country Briefing,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (January 8, 2009).

[2] Minister of Defence, Anne-Grete Strom-Erichsen, “Norway’s Security Outlook,” Ministry of Defence, May 12, 2009. Address made to the Atlantic Council of Finland on the 11th of May.

[3] Gerard O’Dwyer, “Norwegian Strategy Targets High North,” Defense News (November 23, 2009).

[4] For example see the Stoltenberg report, Nordic Cooperation on Foreign and Security Policy (February 2009).

[5] “Shrinking Ice Cover Creates Opportunities and Threats,” Jane’s Navy International (January 2009).

[6] “Shrinking Ice Cover(…)”, ibid.