In the wake of disaster: How the Haiti earthquake is likely to redefine the notion of port security

In the wake of disaster: How the Haiti earthquake is likely to redefine the notion of port security

by Tim Martin, Deaken University

This article is posted with the permission of Risk Intelligence, which published it in its latest Issue of Strategic Insights (January 2010).

***

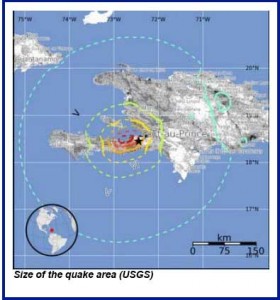

The Haiti earthquake is an important reminder that the security of maritime ports is vital in order to maintain the logistics of aid and fast response in the wake of such a disaster. This is particularly the case for developing nations with minimal infrastructure and/or marginal port facilities to begin with. Although the French and American foothold in the Caribbean island-nation prior to the earthquake has made a difference to help speed up the logistical effort, security initiatives that had been adopted prior to the earthquake did not prepare the port for such an emergency.

This is intriguing since Haiti seems to experience a high level of natural catastrophes. Therefore it is likely that this crisis, more than any other natural disaster, might inadvertently affect how port security management occurs in the future, especially in relation to ports in developing countries that are subject to natural disasters, or for port facilities that may be used as gateways for disasters in landlocked countries.

The concept of port security in recent years has been preventative rather than responsive. The International Ship and Port Facility (ISPS) Code, for instance, appears to have done little to assist in this emergency. The ISPS Code has provided Haiti’s ports with ‘security’ in one sense but not in the sense of securing the ports during disaster relief. Haiti’s ports have been seeking to comply with American and ISPS measures since 2004 via a public and private development project, the Maritime Security Alliance for Haiti (MSAH).

This is a collaboration between a sea of acronyms: the national Port Authority, Association Maritime d’Haïti (AMARH), Association des Terminaux Privés (ASOTEMP), Haiti Terminal, International Maritime Terminal (IMT) and Maritime Logistics of Haiti (MLH). This project was funded by USAID through consultation with Florida Ports Council (FPC) and locally with Association des Industries d’Haïti (ADIH). The Caribbean Central American Action (CCAA) that facilitates Caribbean trade but still has a stated focus on maritime port security and disaster mitigation initiated all of this.

However, the security threats envisioned and level of disaster management planning has not taken into consideration the logistical challenges created by such large-scale destruction of Port au-Prince’s port infrastructure, the key link in the foreign aid logistics chain in an emergency. Therefore the aforementioned bureaucratic alphabet soup did little to provide a contingency plan for a human security-related catastrophe in an otherwise disaster prone region.

The airstrip is the most efficient and time sensitive way to get aid and supplies on the ground. However, the most significant point of entry for long term resupply and reconstruction are the ports. In the case of Port-au-Prince where up to 50% of the city was destroyed, a significant amount of heavy-lift equipment is required which only a deep-waterport facility can accommodate. The Toussaint L’Ouverture International Airport is faced with severe overcrowding and the destruction of the civilian control tower has led to American military controllers assuming command. Civilian relief efforts have been hampered simply due to the overwhelming volume that the small airport is notable to accommodate. For example, Médecins Sans Frontière tried to fly in crucial equipment, including medical supplies but claimed that one oftheir aircraft was sent away due to the bottleneck. Delivery of the aid cargoes that did land was sporadic, hampered by the temporary blocking of Port-au-Prince’s roads with debris, and affected by the lack of trucks for transport. Sadly the death of a number of United Nations experts working specifically on disaster management in the UN office in Port-au-Prince, coupled with the virtual non-existence of Haiti’s government, has only further hampered the relief effort.

Aid and supplies of course are not only needed now but will be for a prolonged period of time.The long-term aid distribution and reconstruction effort cannot be addressed purely with aerial supplies and therefore the port will play the most crucial role in Haiti’s rehabilitation. The distribution of aid in sizeable quantities is the next immediate step to stabilizing Haiti. United States Defense Secretary Robert Gates stated that helicopters were simply not adequate to transport the substantial aid cargo from ships offshore that would meet the requirements of approximately two million people affected by the destruction of Port-au-Prince and its suburbs.

In this case, the maritime ports provide a crucial element in the immediate and ongoing aftermath of such incidents. The capacity of a devastated developing city such as Port-au-Prince to manage its own rescue is dramatically reduced if the critical infrastructure is also damaged or destroyed. Despite the rubble and cracks throughout the network, road transport was more or less intact. Haiti’s principal maritime port of Port-au-Prince was the primary alternate to the airport for airlifting material goods of aid and supplies in sufficient quantities for ongoing needs.

Although Canada was able to fly 200 tons of aid in, it took eighteen flights to do so. Colombia, on the other hand, is sending a naval vessel with 400 tons of aid to Haiti; along with the hospital ship ARC CARTEGENA carrying medical supplies, water and food. An emergency of this scale requires that ships can dock safely and unload effectively. Unfortunately, the maritime port area of Port-au-Prince was heavily damaged.

Consequently, Gates ordered the deployment of US vessels and personnel, both military and civil, to clear the harbor and assess the condition of the only pier within the port that remained standing after the quake. A nearby pier was completely submerged with only its container bridges and cranes above the water. A smaller port facility to the north was also unusable. The remaining South Pier was also damaged and had numerous toppled containers in the water along its length. The short-term options were therefore limited. The two vessels that were berthed at the time, the STELLA MARIS and MICHAEL J. were also damaged when a crane collapsed on top of the vessels. Only 228 of the 1,350 meters of pier space were serviceable and only one truck at a time was allowed on the pier, which appeared to have been compromised structurally from the quake. It was estimated that repairs would take at least 15-30 days.

There are seventeen ports servicing coastal traffic along the Haitian coastline, eight of which receive international traffic, and three of substantial size; Port-au-Prince has the public piers and a private pier at Terminal Varreux SA (also badly damaged). The alternative, the deep water container port of Cap Haitian to the north of the country has become the secondary logistics base for the World Food Program offloading cargo as well as US Naval and Coast Guard vessels.

Another significant problem is access to and from the port as the roads have been cluttered with debris and are partly damaged. The key is repairing all of Port-au-Prince’s maritime facilities as quickly as possible whilst ensuring that the road networks remain usable for the continued incoming aid at increasing levels. US Coast Guard cutters arrived quickly off the coast of Port-au-Prince working with the Haitian Coast Guard, which has a limited capacity in providing either security, assessments, or repairs.

Taking soundings, marking submerged rubble and containers and inspecting the damaged port were key tasks for the joint operation but the security of the port, as in Port-au-Prince itself, is a priority because the city’s surviving law enforcement capabilities are seriously overwhelmed. US troops are flooding into the city and are expected to provide security for the aid and rescue effort but they are not a law enforcement solution, as soldiers are generally not trained in constabulary services. The earthquake damaged the main prison in Port-au-Prince allowing approximately4,000 prisoners, including gang leaders connected to high-level organized crime syndicates to escape into the shattered city. In The virtual absence of a fully functioning police force, these criminals have begun to return to old ways of gang rivalries, controlling turf in the Cité Soleil slum areas of Port-au-Prince, located in the port area. Furthermore, the major road networks leading to and from the port cross through these suburbs. These areas have long been no-go zones where drug trafficking and human trafficking syndicates have flourished. Brazil had a peacekeeping force of 145 soldiers in Cité Soleil but lost 18 of them, including three of its commanders in the earthquake during a building collapse. All of their weapons were looted. Since the initial quake, armed criminal gangs have been accused of attacking rescue workers trying to pull bodies from the rubble, and contributing to the insecurity felt by aid workers and locals. At night, gunshots are often heard, and there are reports of women being raped due to the lack of adequate street lighting. Vigilante groups for the protection of citizens are active with the encouragement from the incapacitated police services but this is not an ideal security solution. The UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon has requested that the Security Council send reinforcements to support the UN peacekeeping mission to Haiti, which will add to the existing 7,000 peacekeepers and 2,000 police already in Haiti. Reinforcements will include 2,000 peacekeeping troops and 1,500 police units.

These extra personnel are likely to stay deployed in Haiti for at least six months and should fill the current gaps in Port-au-Prince security, following the virtual disappearance of the Haitian Police, and an overall sense of a lack of security coordination.

In the port area the US is providing better security than what the rest of the city is experiencing. The US Army’s 82nd Airborne division was guarding the port facilities but the US Coast Guard will likely be the agency in charge of providing maritime security in the longer term lasting months and even possibly years. The US Coast Guard flew in 33 personnel of a ‘Coast Guard Advanced Port Security Team’ on 21 January that consisted of various tactical law enforcement team’ members from Miami and San Diego.

These policing units will provide protection for the US ‘Marine Transportation Recovery Unit’ while they reconstruct the port and the reorganization of the Haitian Coast Guard is vital. The submerged containers and rubble will continue to limit the draft size of vessels supplying the relief efforts organized by the US ‘Agency for International Development’ so this clearance process has been deemed a priority.

US and French divers did manage to clear some underwater obstructions within the first week, however, only shallow draft vessels and barges carrying a maximum of 150 containers are able to access the piers until more work is done. Within a few days a vessel out of Mobile Alabama, the 278-foot US-flagged barge CRIMSON CLOVER, managed to get dockside and cautiously unloaded 100 containers of wheat and vegetable oil. Following this success, other shippers have been contracted by USAID to deliver relief cargoes consisting of around 560 20-foot containers to Port-au-Prince and Cap Haitian from the US ports of Lake Charles (Louisiana), Mobile (Alabama) and Port Everglades (Florida).

A French naval vessel, the FRANCIS GARNIER docked to unload soldiers in the first few days after the earthquake as well as medical equipment and excavators but at the risk of completely toppling the badly damaged pier. The US Sealift Command salvage ship USNS GRASP also arrived to clear the port debris. Secretary Robert Gates expects that the primary piers within Port au-Prince can be reopened within two weeks; however, this seems to be a very optimistic assessment. Barges have been brought in as temporary floating docks for cranes and a causeway barge is currently being used for vehicle traffic. A barge handling ship, an oil delivery ship and a high-speed ferry is also being used to replace the damaged piers. Other naval assets include the US Naval hospital ship COMFORT, which was anchored out at seat ending to survivors who are in critical condition. Overall, naval vessels have generally been more cautious, although it appears that the French and American naval forces have cooperated in getting the port functioning at least within a minimal capacity.

The Haiti earthquake has shown that ports can be vulnerable to natural disasters, which consequently is the primary logistical point for both short and long term aid delivery. When Indonesia was hit by a tsunami in 2004, the only substantial access was by sea, where naval amphibious craft were used. Port security after a disaster will always depend on a number of variables, including extent of damage, logistical needs of a particular situation and the capacity of local authorities to provide security. In the case of the Haiti earthquake, security was immediately recognized as a major issue both in the short and long term. Haiti’s ports are small to medium sized and can only service a limited capacity at the best of times but the problem of getting vehicles to deliver aid supplies when it did arrive in Port-au-Prince, or via Cap Haitian, was compounded by roads blocked with rubble or cracked by the earthquake, and most importantly, a shortage of fuel.

In the long term, the US Military, like the Coast Guard, will need to remain on-station for some months, possibly even years to provide security as the Haitian Government, police force and critical infrastructure are redeveloped. Temporary logistics already in place need to be strengthened and rebuilt. In time, reconstruction equipment will arrive on increasingly larger vessels that will be vital in the long-term reconstruction effort. As this happens, the volume of aid can increase as the needs of the city are reassessed. Although the efforts to get the port up and functioning have been thus far efficient, serious consideration of future disaster management when infrastructure is destroyed must be a part of port security planning. In Haiti, it was fortunate that the US and French military forces were nearby and able to assist, but as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami illustrated, natural elements can incapacitate a port facility as severely as any conventional conflict or terrorist attack with far less predictability. During the post tsunami response, international aid efforts first had to negotiate with the Indonesian government over access to Aceh and consider the fragile political environment between the government and both the Gerakan Aceh Merdeka’s (GAM) political wing and possible splinter elements. Eventually it was realized that the tsunami had destroyed significant infrastructure on both sides of the conflict. Furthermore, Bandar Aceh and the most significantly affected areas had poorly developed and relatively insecure port facilities. Similar to the situation in Port-au-Prince, foreign forces not only had to operate under difficult circumstances but also have had to provide their own security as there appeared to be no contingency plan in place.

Conclusion

Current maritime security upgrades in recent years have only facilitated the day-to-day security of port operations, whereas the security of ports must be part of a wider response mechanism, perhaps in collaboration with regional states through CARICOM, OAS, and of course, the US. The lessons learned in this instance are that indigenous security forces may be non-existent due to corruption, a lack or resources, or a damaged chain of command after a catastrophe, but it is vital that ports and vessels still have a secure operating environment. Haiti has been hit by hurricanes and a major earthquake and was already struggling with its own security and stability before the aforementioned disasters occurred. Developing countries like Haiti (or Indonesia) that clearly do not have the capacity to cope with the added security demands that arise in the wake of large-scale emergencies need to assess all aspects of port logistics security.

The Haitian port facilities and roads will be repaired in due time in order to accommodate the necessary docking of larger ships and the delivery of equipment and supplies. During this time the capacity of the city to provide its own maritime security for the ongoing logistical challenges faced by trying keep Port-au-Prince alive will depend on the goodwill of countries such as the US, French and other donor countries. As more aid supplies and heavy equipment is chartered to Haiti for the relief effort, shippers will need to know there is safe access to permanent or temporary wharfs, and that adequate provisions have been made to unload cargoes onto barges alongside when no other options are available. To those within the shipping industry that are contracted to play a role in the aid delivery to Haiti, the safety and security of their crew and vessel as well as logistical variables to avoid time delays are key priorities.

Despite the considerable efforts of the US reconstruction and security teams, the ongoing nature of aid supply, the fragility of Port-au-Prince infrastructure, the dysfunctional state of the police force, and the potential for select Haitian gang involvement in the port area will threaten shippers who risk their vessels to deliver the much needed cargo. In the short to medium term, port security will rely on external military forces, however, in the long term, port security in the developing world will depend on the lessons that can be learned from Haiti and translated into future port security planning.

***

Timothy Martin is a PhD Candidate at Deakin University, Australia. He specializes in maritime law enforcement cooperation frameworks in the Caribbean and South East Asia and specifically examines drug trafficking and counter piracy initiatives.

———-

***Posted February 24th, 2010