The Aberration of the Large Jetliners’ Growing Market

We’ve just finished Teal’s 2009 World Aircraft Overview, and total deliveries in 2009 grew 3.7% by value over 2008 (it’s remarkably easy to forecast this year’s deliveries when we’re in the fourth week of December). Most of that came from military markets (which grew an impressive 14%), and the civil market grew by a scant 0.2%.

However, while business and regional jet OEMs were clobbered, the large jetliner market grew by 10.1%. Some of that was a recovery from the 2008 Boeing machinist strike, but it represents a remarkable level of growth that’s completely out of sync with the rest of the world. It’s a number that makes this industry unique.

Can you name any other manufacturing or service industry that grew in 2009, aside from foreclosure services and food stamp printing companies?

This means that either our industry is approaching Ringo Starr levels of sheer good fortune, or, more likely, that most of the aircraft industry remains a lagging economic indicator. Assuming it’s the latter, the pain will catch up to us some time in 2010.

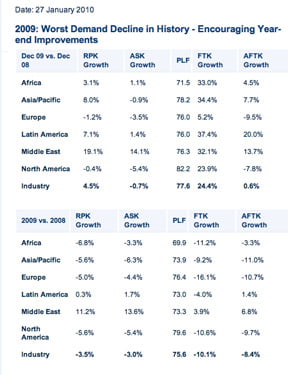

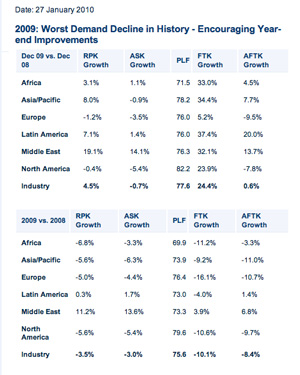

First, the facts. Air traffic is down by about 6% from its peak, and by 10-15% from where it would have been if the economy hadn’t tanked. The International Air Transport Association anticipates $11 billion in industry losses in 2009, following nearly $17 billion in 2008. Fleet utilization is way down, and there are 2,500 jets parked in the desert. Yet jetliner output remains at record highs.

From a forecasting standpoint, there is no way to justify this. But the optimists in this industry come at the problem not from a demand forecasting standpoint but from a financing standpoint (for a good overview from an optimistic financier’s perspective, see Boeing Capital’s Kostya Zolotusky’s latest.

A Replay of the Housing Market Crisis in the Making?

The optimists see assets that can be financed, even if the world is fast running out of customers that actually want these assets.

A key reason this industry has been able to maintain enviable financial conditions is government finance. Most people in the industry are familiar with the growing Ex-Im Bank and European Export Credit Agency (ECA) role in financing aircraft sales, but for a lucid and balanced piece that brings it all together, see Dan Michaels’ recent Wall Street Journal story.

To summarize: The US Government, a highly leveraged institution, whose debt is bafflingly rated AAA, is extending that tenuous debt rating to help build jets for export customers (including Emirates, the national airline of an even more highly leveraged state). On the other side of the Atlantic, Airbus overproduction is propped up by analogous ECA schemes. Government-backed finance now plays a role in about 40% of new jet transactions. This government assistance helps keep employment up and smooth out market cycles. But it’s helping to maintain production rates at a record level, not at a sustainable mid-point level.

The WSJ article quotes Robert Morin, head of the Ex-Im bank, as saying that this financing doesn’t cost the US taxpayer anything. He’s right. Financing jetliners is great business, especially if you’ve got low interest rates.

- But there’s one small detail. As governments help finance unneeded new jets, the resulting overcapacity drives down the value of existing equipment. With the cash-for-clunkers car finance scheme, the government at least made some effort to get rid of the older equipment that was being replaced. But with its financing program for new jets, the government shows little interest in dealing with the surplus equipment that’s languishing in boneyards.

- Another small detail: the existing jetliners whose values are being destroyed are sometimes owned by government-supported financially-distressed institutions. In fact, also this month, ILFC’s debt was cut by Moody’s to a junk rating. This, of course, increases their dependence on government-backed financing. A gross simplification: the US government is putting its cash on the line to build unneeded jets, hurting the government’s share of a portfolio of existing jets.

Then there’s the small question of what happens next. Building lots of new planes made sense when you were getting clunkers out of the mix (anything with a JT8D powerplant). But then 737 Classic and older A320 values starting getting destroyed (United retired its last 737 Classic a few months ago).

Now, we’re watching current generation values and lease rates falling too. According to Aircraft Value News, the value of a 2001-model 737NG is 20% below its late 2007 peak.

What if traffic stays flat in 2010, or if the market takes another hit, for whatever reason? You’ll see more of the same: softening jetliner values, falling lease rates, and, possibly, more government-supported production of unneeded jets. Ex-Im and the ECAs will be on the hook for any jet financing losses that result. This sounds like the housing market. Fannie Mae and its brethren did fine when values were rising. It’s when times turn tough that governments lament financing overcapacity.

So, the first thing to worry about in 2010 is that this seemingly happy arrangement—government financing being used to prop up jet production in a seriously depressed market—goes horribly wrong. But the more likely scenario is that we simply run out of airlines willing to take jets. As airlines defer, narrowbody production rates will get cut, restoring sanity to a completely crazy market before the governments involved can make things worse.

———-

***Posted February 1st, 2010