By Ambassador Jon Glassman

Ambassador Jon Glassman is a retired career Foreign Service officer who is currently Director for Government Policy of the Northrop Grumman Corporation’s Electronic Systems sector. While at the Department of State, Ambassador Glassman served in many countries, including Afghanistan. Ambassador Glassman also has served as the Assistant to the Vice President of the United States and as Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs. The views in this article are his own and do not reflect neither the views of Northrop Grumman Corporation nor the United States Government.

***

S400 Battery Movement

Deterrence Revisited?

The United States is a unique country in that its geographic isolation has spared it from depredations from strong neighbors. While shocking, Pearl Harbor and the terror attacks of September 11th, 2001 also serve as reminders of how infrequently the U.S. has been assaulted by outsiders.

It should come as no surprise that entities like Russia, which suffered 20 million dead in World War II, China, which lived through two centuries of humiliation and episodic foreign occupation, and continental Europe, which lost the flower of its youth in two devastating world wars, would not share in the buoyant optimism that marks much of the American experience.

Tragedy can lead in one of two directions: paralysis, or a strenuous effort to seek survival and dominance. In the defense realm, one can sense parts of Europe and Japan drifting toward the former and China and India toward the latter.

These decisions are driven in part by economic performance and by political decisions that generate or deny the resources required to sustain national security. Such resources can be generated internally or obtained through foreign assistance.

The marriage between the desire to protect or dominate and the availability of resources creates the dynamic for change in global security. Today’s weakling can become tomorrow’s impregnable fortress given the fusion of technology and domestic or foreign capital.

Conversely, in America’s case, failure to adequately fund technology and procurement could make it possible to neutralize U.S. military advantages or to generate what geopolitical strategist Fritz Kraemer called “provocative vulnerability.”

It is against this background that America must confront those seeking to reverse tragic pasts and overcome current shortcomings.

Efforts by the U.S. and its potential adversaries to defend their homelands, along with land and marine bases, is an important part of this problem set. While sheer size helped protect 19th- and 20th-century Russia and China, that advantage exists today only if nuclear deterrence holds.

Yet, even if nuclear forces are held in check, the possibility of coercion endures. If American aircraft and missiles can penetrate the Eurasian land mass or, as in recent years, individual countries such as the former Yugoslavia and Iraq, the United States will continue to enjoy dominance.

And, should the United States create a shield that calls into question the viability of deterrence, or protects U.S. bases from attack, potential adversaries may seek to either defeat or neutralize that shield.

Russian and Chinese Defensive Systems Buildup

Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, with his characteristic bluntness, summarized the situation last December: “There could be a danger that, having created an umbrella against offensive strike systems, our partners may come to feel completely safe. After the balance is broken, they will do whatever they want and grow more aggressive.”

Putin’s near-term solution is to enhance offensive systems, an effort that would mean improving the ability of Russian weapons to penetrate U.S. defenses.

Addressing the issue of Russian defenses, Putin has said: “We aren’t planning to build a missile defense of our own as it’s very expensive and its efficiency is not quite clear yet.”

Putin’s uncertainty is significant. Russia built a nationwide air defense system with ground sensors, weapons and air forces to sustain it. Its technological capability in this domain is renowned, but it can remain strong only through continued investment and procurement, and by finding foreign customers.

As Russia moves through its $200 billion force modernization, decisions on whether to expand domestic air and missile defense capabilities will have important consequences for foreign customers, including China and India, who have relied on Russian defensive technology, and on those, such as Iran, who view Russian systems as a way to escape Western dominance.

For Moscow, a decision to improve defenses will also make it more desirable to co-invest with China and India and make sales to capital-rich oil states and others in order to reduce its own procurement costs.

After a decade of benevolent neglect, Russia’s capabilities are beginning to revive, albeit gradually. Beginning in the 1980s, variants of the Patriot-like S300 aircraft and cruise missile point defense system were deployed around Russian high-value targets and sold to foreign customers.

Starting in the late 1990s, Russia began to develop a successor S400 system with added ballistic missile defense capability. This system, reportedly benefitting from a $500 million Chinese investment, has a 400-kilometer (km) range and will offer layered protection around high-value targets and base areas.

Last year, General Aleksandr Zelin, commander of the Russian air force, announced plans to add five, eight-launcher, 32-missile S400 batteries to the two S400 batteries already in existence. That is scheduled to happen this year, with another eight batteries budgeted through 2015.

In addition to China, the S400 has been aggressively marketed in the United Arab Emirates, Greece, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran. Delivery to Iran has been delayed due to Western objections.

At the same time, the Russians are building a new generation S500 to be ready in 2012 with the “capability to destroy hypersonic and ballistic targets” and engage10 simultaneous targets at a range of 600 km. This new system, coupled with the S400s, is designed to create by 2020 the foundation of a new air-space defense branch linking:

- Space-based assets;

- New perimeter acquisition/space surveillance radars now being installed in the northwest and the south and slated for other future border sites;

- Legacy and upgraded area surveillance radars and passive detection assets;

- Improved MiG 31 Foxhound aircraft to cover the gaps between the high-value ground missile-defended areas;

- Upgraded army short-range systems.

The reborn Russian defensive system appears to be a collection of newly improved but loosely-integrated capabilities. But its real importance may lie in the security it could provide to China and other export customers against the West.

The Chinese have 128 Russian S300 missile launchers and 64 HQ-9 domestically-produced equivalents and appear to be following the Russian defensive strategy. They, too, are invested in the longer range, more capable S400 and will presumably upgrade their current system to new-level Russian performance with imported or domestic production.

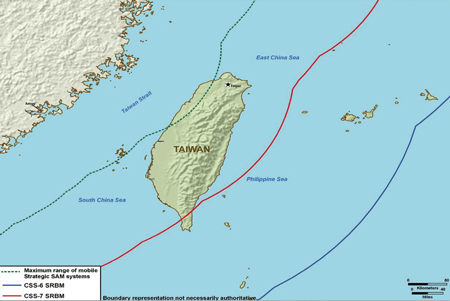

The Chinese have gone a step further, however, They have methodically worked to bolster their defenses in the east — in advance of a potential confrontation with Taiwan and the U.S. — by deploying 500 new-generation Russian and Chinese fighters with high-end advanced Russian air-to-air missiles, more than 1,000 ballistic missiles and 350 land-launched cruise missiles to attack regional airfields, sensors and command-and-control.

Chinese over-the-horizon detection radars and ballistic and cruise missile improvements also have been fielded to put U.S. aircraft carriers and Aegis ships at risk.

Beyond the Chinese and Russian borders, the incentives for proliferation of their defensive systems remain high. This would allow Moscow and Beijing to lower domestic unit costs and maintain their high-tech industrial bases. However, these systems, even if exported at top performance levels, would be difficult to operate and maintain by host country personnel. This might lead customers to import Chinese and Russian support staff, thus complicating U.S. interventions.

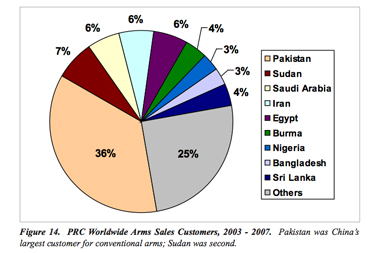

Credit: DoD’s Annual Report to Congress ,

China Military Power 2009, page 58

***

As the United States and other Western powers consider what, if anything they can do to affect defensive investment decisions in Russia, China and export markets, thought should be given to a variety of issues:

- Are we right to limit F-22 production and export given that the aircraft could putatively overcome the newest Russian/Chinese defensive systems, thus rendering investment in them pointless?

- Is F-35 production fast enough to confront the new defensive systems early on with overwhelming electronic threats?

- Should we accelerate deployment of Actively Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radars with electronic attack capabilities in third- and fourth-generation U.S. fighters?

- Can we concede to allies an electronic attack role?

- Should we accelerate deployment of a stealthy, weaponized Navy unmanned combat air system (N-UCAS)?

- Should we incorporate foreign “loitering munitions” and develop a Concept of Operations (CONOPS) with our allies for using the Euro Hawk unmanned aerial vehicle to engage mobile defensive system sensors and weapons?

- Should we accelerate efforts to develop new standoff strike assets?

- Are there any arms control or commercial approaches to preventing export of the Russian S400 and S500 systems, or the Chinese HQ-9 missile?

———————–

*** Posted on March 16th, 2010

*** For further information, see for instance: