Europe is in the throes of a fundamental change. The dynamics of change associated with the Great Recession, and the ripple effects on European societies are intersecting with a Euro crisis. The currency crisis reflects underlying pressures and strains within global economies. The intersection between the economic pressures with those from outside of Europe, the engagement in Afghanistan, the rising challenges of Iran, the need to guarantee Iraqi sovereignty are creating a potentially explosive brew of political pressures. The economic and political pressures are likely to lead to significant pressures on defense procurement, which, in turn, intersect with American dynamics to create substantial pressure for a downturn in Western power projection and military capabilities.

The dynamics of change in 2010 will be explored in two parts.

- The first part below is provided by Harald Malmgren and addresses pressures on the Euro and the Eurozone economy .

- The second part will be provided by Robbin Laird and will examine the intersecting pressures associated with defense and potential foreign crises.

***

European Economies Under Strain in Early 2010: How Serious is the Euro crisis?

By Dr. Harald Malmgren

A growing number of hedge funds and institutional investors are betting on a further decline in the Euro relative to the dollar, with some of them questioning whether the Euro can remain a viable currency. Early in 2010, world press and media treated the Greek financial crisis as the biggest challenge to confidence in the Euro. After European leaders promised that a European solution would be found, by March the crisis was declared over.

The Greek Crisis: Only the Tip of the Iceberg?

Major global investors do not agree the Eurozone’s crisis is over. Since its peak last year, the Euro fell about 10% against the US dollar. Now, markets show a record level of contracts to “short” the Euro, betting that the Euro will fall much more. The negative perception of the Eurozone reflects a growing belief among global investors that Greece is just the first in a series of public and private debt crises among all Euro members.

Investors betting against the Euro see crippling budget deficits well into the future alongside rising unemployment, economic stagnation, and increasing chance of deflation in all of the Euro member nations. Market pessimists believe that Euro members will be economically unable and politically unwilling to help each other because they all have huge borrowing needs and will be increasingly competing with each other in flogging their own debt.

European politicians, unwilling to open doubts about their own policies, have taken the opportunity to blame “speculators” for exacerbating the Greek crisis and undermining confidence in the debt of other Euro members. Political leaders pledged to “ban” trading in evil credit default swaps (CDS) as if this would magically banish Euro pessimism. The response of traders was to reduce trading in CDS and increase bets against the Euro.

Although officials in the other Eurozone countries declared they would assist Greece, it turned out to be extremely difficult to find consensus on what to do. The only thing that could be agreed was that the Greek government would have to come up with even deeper budget deficit cuts. Even then, signals emanated from Berlin that the German government would not agree to financial aid. In desperation, Greek Prime Minister Papandreou declared that if the European friends of Greece could not help financially, Greece would turn to the IMF. Unknown to the Greeks, French Finance Minister Lagarde had already advised IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn in January that the IMF should stay out of what was an internal Euro matter. After Papandreou’s declaration, ECB President Trichet publicly stated that he wished to exclude the possibility of further IMF involvement with Greece.

The unsaid implication of this stance is that if Greece wants to call upon the IMF then it should first have to decide to exit from the Euro. Underlying this hard stance was recognition that IMF intervention inside the Eurozone would bring international intervention in the internal decisions of all Euro members. For many European governments, this would constitute yielding sovereignty to “outsiders.” From the Euro’s inception, members had long resisted yielding sovereignty to each other – much less to an outside third party.

In response to pressures for greater efforts to curb its deficit, a new Greek austerity budget was approved by the Greek parliament in March. Euro bears concluded that deep cuts in spending and jobs combined with tax hikes would virtually assure return to recession. The new budget assumes that Greek citizens will acquiesce, even though unions and students are mounting strikes and disruptive demonstrations aimed at blocking austerity.

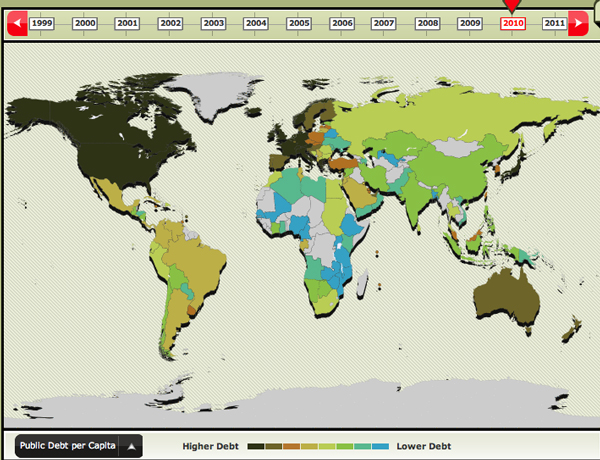

What has been overlooked is that the Eurozone debt crisis extends far beyond Greece. Whatever happens in the coming weeks, the Greek economy will deteriorate further and its borrowing needs will escalate later this year. At the same time, borrowing needs of other Eurozone members will grow. It is already evident that Portugal and Spain will have to issue growing debt while suffering fiscal deterioration, further downgrades, and political resistance from strikes and disruptive demonstrations. Rating agencies have already put their debt on “negative watch” and are preparing for downgrades of yet other Euro members’ debt. These borrowing problems will be made more challenging by huge borrowing needs of the three biggest Euro members, France, Germany, and Italy. These three together will need to raise more than €1.2 trillion in combined new issuance and rollovers of existing shorter term debt in coming months. As 2010 progresses, the Euro member governments collectively will have to raise ever larger capital to fund their growing deficits. The ratio of government debt to GDP of many members will reach and even exceed 100%.

When the ECB made huge liquidity injections into the Eurozone banks from 2007 onwards, it found that banks were bringing low quality sovereign debt as collateral in exchange for Euros. Member governments like Greece were able to float bonds in the expectation that they would be bought not only Greek banks but also by other European banks because of the ECB’s continued willingness to take any Eurozone sovereign debt as collateral. In effect, national governments were able to spend without concern for burgeoning deficits because debt was readily financeable. The ECB’s form of “quantitative easing” was to issue capital on the back of undisciplined fiscal policy among its members. Now, however, the ECB is aware that it cannot go on encouraging inflated budget deficits and it has warned that next year it will stop accepting as collateral sovereign debt graded below A-. That likely puts not only Greece but others out of the game.

Critical Flaws Underlying the Euro

Initially, the Euro was perceived by global security experts and market analysts as a “glue” that would hold Continental Euopean nations together. Since then, it has not been recognized that there are fundamental flaws underlying the Euro – flaws which were not visible during years of strong world economic growth, but which are now appearing as large cracks in the currency’s foundation.

- One major flaw is the Eurozone’s dependence on external demand as its primary driver of economic growth. Growth in exports depends upon growth in growth in world trade. The head of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Pascal Lamy, just announced that world trade contracted by 12 percent in 2009, a much bigger decline than previous estimates. This decline followed an abrupt and dramatic fall in world trade which began in the fourth quarter of 2008, and which has now become the longest contraction since the Great Depression.

Since the 1940’s, world trade grew by almost twice the rate of growth of world GDP. Economies that had been decimated by world war, and other developing economies that wished to grow faster, were enabled to jump on to the express train of exports to accelerate domestic economic growth. Dependence on rapidly growing external demand developed into an addiction, as domestic policies were revised to strengthen competiveness while keeping domestic costs suppressed. Unfortunately for the Eurozone, the growth of world trade now no longer seems to be an express train running at high speed, but instead resembles a local train with frequent stops and random diversions onto sidetracks. The rate of growth of world demand for exports has long depended on consumption in the larger, more advanced economies, and most particularly on US consumption, but consumption has slowed in the US, and it is doubtful that it will experience robust recovery any time soon.

The composition of exports from the Eurozone, and especially from Germany, is highly concentrated in manufactured goods. When world trade collapsed in late 2008, world demand fell far below the productive capacity of the exporting nations. The result was worldwide industrial overcapacity. Investment in new projects that were already under way in 2008 to increase productive capacity continued, especially in China, so that by 2010 the level of worldwide industrial overcapacity had grown. In this context of global industrial overcapacity, the Eurozone’s overdependence on external demand is a fundamental flaw underlying the Euro which was not visible when global growth was robust.

- Another basic flaw underlying the Euro was revealed in the failed effort to cobble together a bailout for Greece. The member governments are still caught in the prohibition that the “Union” shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of its members, thereby excluding the possibility of dependency of “undisciplined” members on the others.

- Another flaw in the foundation of the Euro is embodied in the agreement of the initial members of the Euro that national autonomy in both fiscal policy and in financial regulatory policy should be preserved. They did recognize the need for a single central bank if there was to be a single currency, and they assigned monetary policy to that central bank. However, they refused to yield sovereignty over fiscal policy to each other. A common currency with extreme variations in fiscal policies would not be sustainable without some discipline, so they concocted the Stability and Growth Pact in which members are required to limit their budget deficits to 3 percent of their respective national GDP. Adherence to this guideline was subject to some degree of financial manipulation to conceal the extent and timing of deficits, but as long as economic growth continued it helped to provide a practical degree of fiscal discipline — until the collapse of credit markets and the 2007 emergence of the Great Recession. The members’ responses to the Great Recession varied widely, but the ratios of all deficits to GDP exploded. The current average has already risen above 7%, with some countries like Greece in double digits. In these circumstances, members have chosen to ignore the Stability and Growth Pact. Political survival of governments took precedence over fiscal prudence, and the budget deficit discipline has broken down.

The creation of a European Monetary Fund (EMF) is the latest idea to address possible mutual support of members, but German officials remind that such a fund would require a change in the treaties underlying the Eurozone, changes which would require severe sanctions on members that did not maintain budget discipline. The troubled Euro members want financial help, but not sanctions. - When the Euro was introduced, the members of the new common currency also refused to agree to give up their national bank supervision and financial regulatory powers to the ECB. The ECB can set interest rates, but it cannot examine the strength of individual banks. The national governments do not want officials from other member governments to become privy to the circumstances of their own banks. When the credit crunch gripped financial markets from the summer of 2007 onwards, the ECB could only respond by injecting liquidity into the Eurozone economy, without addressing the rapid deterioration in the liquidity and solvency of many Eurozone banks. This constituted yet another flaw in the Euro’s structure.

Some might argue that a weaker Euro will help pull the Eurozone out of prolonged slump. The Euro has already fallen by 10% against the dollar. Would further decline be beneficial? If the world economy would resume the growth trajectory which prevailed prior to the Great Recession, then a weaker Euro would enable increased demand for exports, helping to revive economic growth among the Euro member nations. Depreciation of the Euro would, of course, mean enabling Europe to take a larger share of world markets.

The problem in 2010 is that world trade has not yet convincingly demonstrated robust recovery from the severe contraction of the last 15 months. Many major economies are still demonstrating symptoms of economic slump. In a context of slower growth in world trade, and slower growth in consumption in the US, it is not clear how beneficial a further decline in the Euro would be for Eurozone exports. It is possible that world demand would not respond to a weaker Euro, but instead, in a context of global industrial overcapacity, a weaker Euro might encourage deflation in industrial goods in world trade while increased import costs would intensify inflation pressure at home

Ultimately, the most fundamental flaw underlying the Euro is the continuing unwillingness of members to yield meaningful sovereignty to each other, or to a common Eurozone overseer. Since its inception, the Euro has never been stress tested. Under increasing stress now, it looks likelier to outsiders that the Euro will continue weakening and may even come apart.

——–

*** Posted on March 16th, 2010