From Global War on Terrorism to Grass-Roots Maritime Security

By Sebastian Bruns, Assistant Analyst, Risk Intelligence

Sebastian Bruns is an Assistant Analyst for Risk Intelligence and works on naval strategy and maritime geopolitics. He holds a Masters in North American Studies and is a PhD candidate at the University of Kiel, Germany.

The article below was originally published in Strategic Insights, No. 25 (July 2010).

***

11/05 /2010

“[Africa Partnership Station] is inspired by the belief that effective maritime safety and security will contribute to development, economic prosperity, and security ashore.”

(U.S. White Paper, Africa Partnership Station)

Africa is back on the maritime security map. For ship owners, masters, CSOs and SSOs who have long been concerned with African trade and maritime threats to their crews and vessels alike, this political shift signals a timely endorsement of the inherent challenges that the continent offers.Stability and prosperity in Africa are obviously good for Africans and a globalised world, and a well-governed maritime environment will contribute to overall security and prosperity. That is why African littoral nations should develop their own ability to govern their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones. Observers regard persistent international effort delivered on African terms as the key.

At the same time, the goals of Africa Partnership Station (APS), the U.S.-led approach, coupled with its political objectives and its implementation raise a number of questions to be outlined below. APS is one of three so-called global fleet stations designed to framework frequent deployments of maritime forces (naval ships, coast guard, air squadrons, naval construction battalions).

Moving Beyond a Narrow Focus

Although the fact that President Barack Obama’s paternal roots lie in Kenya may perhaps suggest a somewhat natural coming-into-focus of Africa into U.S. foreign and security policy, American commitment had been beefed up as early as 2007. During the tenure of Obama’s predecessor, George W. Bush, the first APS deployment opened up a new chapter in U.S.-African relations. APS signaled an unprecedented engagement off the coast of sub-Saharan Africa in an effort to strengthen maritime security and safety.

Politically, it is in line with the United States’ ‘Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower’ (also published in 2007), which calls for cooperative international maritime engagement, covering the vast spectrum that maritime security and safety entail.

APS is one of the first examples trying to put this strategy in place.

Thus, it is fundamentally different from the classic role and identity of Navies, over decades largely concerned with battles at sea, anti-submarine warfare, convoy operations, naval gunfire support for land operations, or muscular (in fact, nuclear) deterrence.

In effect, plans to beef up maritime security in African waters reach back to 2003. It is crucial to understand that in those years, foreign policy and maritime security were seen in the larger context of the postulated ‘Global War on Terrorism.’

Thus, any efforts to curb piracy in Africa or to act against shore-based threats to maritime security were thought to be under the general umbrella of a powerful counter-terrorism policy, thus allowing for greater political leverage and more funds to be appropriated to the issue.

With a disregard for the differences and shades of grey between maritime security challenges, APS was off to a shaky start: The new-born U.S. African Command, a military governing body solely devoted to Africa, has not been able to relocate to an African country willing and able to sustain a larger U.S. military presence, underlining the difficulty that military planners had to overcome for their endeavor. Therefore, AFRICOM is currently headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany. APS is the responsibility of U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa, who in turn had to shape APS in a different way.

Unlike port visits in Europe or elsewhere, naval ships on duty with APS cannot rely on a high level of port security and a reliable harbor infrastructure in the countries that they are calling. Many ports are not equipped to handle warships with a larger draft. Unlike maneuvers with allies that often sport aggressive names and rely on firepower and deterrence exercises, APS is distinctly different in its approach, and even by the collegial name of the operation itself, thus a textbook example of the new concept of smart power (the marriage of soft and hard power means).

Unlike U.S. naval forward presence in the Mediterranean Sea, which is being maintained by the presence of a standing fleet headquartered in Naples, Italy, APS aims for persistent presence. This is not limited to a certain ship, platform, type of engagement, nor is it only delivered only at certain times of the year or to a certain country region of Africa.

Unlike previous sporadic engagements in Africa (most notably the West African Training Cruise of the 1970s), APS is specifically designed to sustainably improve relations with African nations and support regional maritime professional education, maritime domain awareness, maritime infrastructure, and maritime response capability.

Objectives: Strengthening Maritime Awareness

Inasmuch as the naval effort is laudable, general objectives rather than concrete benchmarks have prevailed in the political statements. According to APS’s website, it believes in a “recognized relationship between maritime security, maritime governance, development, prosperity, stability, and peace” and has thus “trained thousands of military personnel in subject areas like seamanship, search and rescue operations, law enforcement, medical readiness, environmental stewardship, and small boat maintenance” to date.

In short, APS aims to strengthen maritime domain awareness (MDA) through a number of measures. These include, but are not limited to, improving equipment and education, enlarging medical capabilities, joint exercises and capacity building by training the trainers. Furthermore, public diplomacy such as joint sports exercises; basic medical aid or U.S. Navy Seabees (engineers) efforts aimed to strengthen the smart power component of APS serve to underline the partnership aspect of the program.

However, smart power successes are inherently difficult to measure. The absence of hard military objectives, or even an ambitious political goal such as reducing piracy in the Gulf of Guinea to zero, underline that APS is at least as much about African security as about U.S. security interests. It is, in short, a highly strategically and politically charged operation.

At the same time, it is certainly neither a simple feel-good cruise nor designed to militarize America’s Africa policy, or those of its NATO allies. In fact, while a generally improved MDA is in the interest of the United States – for example, such as the U.S. approach to limit its dependency on foreign oil that needs to pass maritime choke points (and instead, for example, fostering economic ties with the oil-producing countries in West Africa) – any strategic advantages are merely medium, or even long-term, in style and do not singularly benefit the U.S.

For African nations involved in APS, the effort leads to a welcome opportunity to build MDA capacities and to strengthen their relationship to Washington. By the same token, Washington will have to address and overcome fears of neo-imperialism, militarization, and growing Chinese influence in Africa.

Missions: ‘Good Boat Diplomacy’

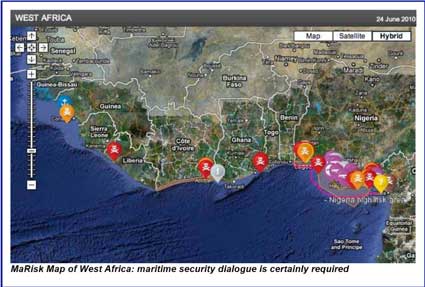

Initially, a focus of the international efforts through APS has been West Africa and the Gulf of Guinea. 11 nations around the Gulf joined to approach the U.S. in order to gain help and support to combat challenges to maritime security. It was hoped that U.S. efforts through APS would be able to advance basic seamanship, small boat handling, VBSS (visit, board, search and seizure) techniques, search and rescue (SAR), data management and the setting up of operations centers for African law enforcement.

Operational measures included the education of African officials onboard of U.S. vessels, training of the local military, and capacity building in order to fight illegal fishing, combat drug trafficking, smuggling, illegal bunkering, and piracy. From using small Landing Craft Units for port visits, to delivering aid onshore, to joint exercises from maneuvers and even basketball games and training in martial arts, APS brought a wide variety of measures to the table.

In their own words, U.S. naval planners aimed for “good boat diplomacy” instead of “gunboat diplomacy.”

Delivering food, water, and medical assistance is yet another issue for military and policy planners. According to a U.S. AFRICOM press release, APS in 2008 engaged 15 West and Central African nations; saw the participation of 1,500 maritime professionals; hosted 79 ship riders from 10 nations; conducted numerous information sharing, sea-basing and maritime patrol operations with Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Senegal, and Liberia; provided an extensive medical and media outreach; and saw the first known U.S. Navy engagements in Equatorial Guinea and Angola as well as the first U.S. Navy theatre security cooperation engagements in Nigeria.

According to a policy brief in Washington in January 2010, anti-piracy training paid off in the Gulf of Guinea, when Benin recently “conducted a counter-piracy operation where they took back a ship that had been captured by pirates. The chief of the Benin navy said later that his success, his navy’s success, was directly attributable to the Africa Partnership Station and the efforts that we have expended in partnering with Benin and helping them improve their ability to get out on counter piracy operations.”

In the last two years, East Africa has drawn increased attention for APS as well. The outburst of piracy in the Gulf of Aden, the Somali Basin, and the east coast of Sub-Saharan Africa has prompted the U.S. (whose 5th Fleet is a standing force in the general area, covering the volatile Persian Gulf/Strait of Hormuz area) to dispatch some vessels under the APS banner. In February 2009, this expansion towards South and East Africa called port in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Kenya.

At a time when the increased piracy threat incited a broad coalition of naval powers to come together to oust piracy, military and policy planners know very well that the threats to maritime security in East and West Africa could hardly be further apart from each other.

Piracy is structurally different in the Gulf of Guinea; attacks on oil rigs and approaches in port are typical. Off Somalia, piracy is occurring on the high seas. In West Africa, most states are able to maintain a low level of stability, offering an opportunity to build upon when training naval and maritime forces.

On the other end, in Somalia, the classic failed state that is home to civil wars, despair, al-Shebab fanatics and violence, offers no starting point whatsoever to undertake diplomacy through maritime means.

Platforms: Form Follows Function

Past APS deployments have shown a general trend for form to follow function, although it was not really clear at the outset which class of vessels would serve the underlying interest of APS best. Therefore, it did not come as a surprise that a high-speed catamaran served in the area as well as a guided missile cruiser and even the 40-year old behemoth USS NASHVILLE, an ageing Austin-class amphibious transport dock.

To test the waters before APS was officially kicked off, the Navy even dispatched the repair ship USS EMORY S. LAND to Africa in 2005, possibly the most non-threatening military vessel one can think of.

The USS NASHVILLE, which sailed to Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria, Gabon, and Sao Tome and Principe in 2009, encountered some unique problems herself: Due to her outdated construction, she could not call on the port of Libreville, Gabon, where the waters were not deep enough for the 17,000-ton veteran amphibious ship to navigate safely.

This, in turn, was not only a lesson learned on the absolute need for reliable intelligence and information on the conditions in the port, but also served as sales promotion for the newer gas-turbine powered amphibious vessels such as the Whidbey-Island class dock landing ships (the USS FORT MCHENRY made 19 port visits in 10 countries as part of her 2007 APS deployment).

This class of ships has proven itself practical for APS. In fact, in 2009, The Netherlands, by way of her HNLMS JOHAN DE WITT – yet another amphibious landing ship – became the first non-U.S. country to lead an APS mission (the second European ship to lead the mission was the Belgian Navy’s BNS GODETIA, a command and logistical support vessel designed for anti-mine warfare, in early 2010).

Amphibious transport docks are easier and cheaper to operate than other conventional warships, offer more cargo space for the diverse needs of APS, and provide better accommodation.

APS uses naval assets as mobile schoolhouses, repair shops and medical clinics to deliver training, material, scientific and humanitarian aid.

Another valuable asset of APS has proven to be the involvement of the United States Coast Guard.

During the summer and fall of 2008, the USS LEYTE GULF (a TICONDEROGA-class guided missile cruiser) and the USCGC DALLAS, a U.S. Coast Guard cutter, performed a joint mission intended to bring African law enforcement officials onboard. It was designed to underline the increasingly blurry line between the defense of inshore and offshore maritime good order, traditionally a task divided between navies and coast guards.

The cruiser, while it does sport the classic shape of a warship, did not offer as many genuine operational advantages to APS as her Coast Guard companion. The DALLAS, although considerably older than the cruiser, has a long history of nation-building training and professional capacity-building expertise, looking back on operations in the Caribbean and the Mediterranean.

The Coast Guard traditionally has a much larger field of expertise than many other coast guards, going far beyond inshore, littoral or EEZ tasks. At the same time, its white hulls and understated armaments are anything but threatening to onlookers.

Although prone to intra-service competition with the Navy over funds and missions, the Coast Guard proved to be, in the words of one analyst, “the perfect fit for Africa” in order to foster maritime law enforcement, search and rescue operations, environmental protection and aids to navigation (subjects that mirror Coast Guard missions).

The high-speed catamaran HSV SWIFT, an innovative platform designed for sea basing (thus eliminating the costly and potentially politically hazardous need for bases on shore), has seen repeated use as part of APS. The vessel served as a potent force enabler and also hosted numerous ship-riders: African maritime security officers or sailors who receive on-the-job training paired with the regular crew, a measure successfully employed on other vessels as well.

Assessment: Interesting Prospects Ahead

Assessment: Interesting Prospects Ahead

Although APS would like to be seen as a solely “good ship” diplomacy effort, there are some inherent shortcomings and criticism to be addressed. The command structure has already been mentioned. The joint effort by coast guards and navies is laudable, and certainly stems from the U.S. understanding of a sea-going U.S. Coast Guard role.

At the same time, African security needs call for a much larger coast guard presence than navy ships could ever provide. To fight piracy, illegal fishing, human trafficking, theft, illicit trade and narcotics smuggling, requires vessels (and crews) adapt to typical coast guard roles.

However, only the U.S. Navy as a forward-positioned navy can supply enough manpower and vessels to APS. From that, a stronger naval role follows. Policy objectives – preference for naval assets vs. a stronger and much more visible U.S. Coast Guard role – confuse and might even handicap some APS objectives.

It is not entirely clear how feasible the two-front approach of APS to both East and West Africa can really be. While naval assets confronting piracy is an important factor, it is – in relation to the objectives of APS – only one of many maritime challenges and, moreover, means confronting the symptoms rather than the sources. Operational demands and strategic goals may not necessarily completely overlap.

The involvement of many European nations (such as the Netherlands, Portugal, France and Belgium, all of which share their own ties to Africa mostly through a colonial past) through platforms and naval officers gives APS a broader legitimacy and, as a by-product, fosters international cooperation between naval forces.

APS also makes it its goal to call on as many African nations as possible, involving members of law enforcement agencies and maritime security experts instead of focusing on a single nation at a time.

The littoral environment (commonly defined as the combination of a maritime zone near the coast with confined and shallow waters as well as busy shipping channels and harbor approaches and a zone on land roughly the distance within the reach of conventional maritime force capabilities) will continue to play an increasingly central role, offering new opportunities and challenges far from aircraft carrier groups and nuclear-powered submarines.

The U.S. Navy’s new Littoral Combat Ships (FREEDOM-/INDEPENDENCE-class), fast shallow-draft vessels such as the SWIFT-class sea-basing catamarans due to be added to the fleet, auxiliary vessels which serve as multi-mission platforms, and perhaps even riverine capabilities, are regarded as being future assets to development with African partners.

As long as there is a political will to undergo joint training in basic seamanship and maritime security education and practice, APS will be of great value for Africa – and for the U.S. From positive public relations effects (i.e. sailors helping to protect a sea turtle preserve in Sao Tome and Principe) to concrete help (i.e. in training Nigerian forces to counter the threats of piracy and oil-refinery attacks), APS offers a wide spectrum of opportunities.

What remains unclear is how the postulated whole-government approach and the integration of all forces can help achieve concrete benchmarks in improving maritime security.

If APS is fundamentally about breaking down barriers between countries, navies, U.S. agencies and other institutions, then both the domestic, bilateral and international dimension will be immensely interesting to follow. Some inherent challenges based around the U.S.’s image in the region and certainly cooperation and willingness of African states will also remain.

The vast spectrum of different and difficult challenges, overlapping transnational threats, factors and actors – and the absence of a yet to be defined strategic goal – will raise interesting prospects for Africa Partnership Station.