(Credit: http://www.dawn.com)

11/05 /2010 – The Obama administration has decided to pursue a more “proactive” air campaign against the Taliban insurgents and Islamist terrorists operating out of the autonomous tribal regions of northwest Pakistan. Afghan border outposts come under constant attack by Taliban and Haqqani-affiliated insurgents based in Pakistan, especially in North Waziristan. The guerrillas sally forth from their sanctuaries in Pakistan and attack Afghan army outposts in eastern Afghanistan, then flee back across the border with NATO air crews in hot pursuit. From these same sanctuaries, the terrorists plan and develop plots against civilian targets in foreign countries, including in Europe and the United States.

The White House and the Pentagon have become increasingly frustrated by the presence of the Taliban sanctuaries on Pakistani territory and the inability of the Islamabad government to establish control there. The Administration made a decision to double the number of U.S. combat troops in the country as part of its strategy in Afghanistan.

The impending December 2010 deadline for reviewing the results of the Afghan surge strategy has made the Administration especially eager to show some positive military results before then.

While still declining to send U.S. ground forces across the border into Pakistan, the Pentagon has increased the use of both manned helicopter attacks along the border and unmanned aerial vehicle strikes for striking targets deeper inside Pakistani territory. The purpose of these attacks is to deny the insurgents and terrorists a safe haven from which they can infiltrate men and material across the porous Afghan-Pakistan border as well as organize terrorist attacks on foreign countries.

While still declining to send U.S. ground forces across the border into Pakistan, the Pentagon has increased the use of both manned helicopter attacks along the border and unmanned aerial vehicle strikes for striking targets deeper inside Pakistani territory. The purpose of these attacks is to deny the insurgents and terrorists a safe haven from which they can infiltrate men and material across the porous Afghan-Pakistan border as well as organize terrorist attacks on foreign countries.

In one of these operations on September 30, two ISAF Apache helicopters attacked a site from which the insurgents were reportedly preparing to fire a mortar at a coalition base in Afghanistan’s Paktia province. After attacking this target, which resulted in their briefly crossing into Pakistani territory, the American crews concluded that they were taking small-arms fire from the Mandat Kandaho border patrol post, located some 200 meters inside Pakistan in the Kurram Agency. In self-defense, the helicopters re-entered Pakistani airspace and fired two surface-to-air missiles that destroyed the post, killing three members of Pakistan’s paramilitary Frontier Corps and wounding three others in the process.

The whole affair was marked by confusion. The incident occurred before dawn, which made it even harder to avoid straying across the Afghan-Pakistan border, with its disputed boundary that typically lacks natural geographic distinctions and is not clearly demarcated.

According to the Pakistani military, the Frontier Corps troops, a poorly trained and equipped tribal patrol force, fired “warning shots” to caution the helicopter crews that they had entered the territory of Pakistan’s upper Kurram Agency. A joint NATO-Pakistani inquiry concluded that the two helicopter crews misinterpreted the shots as an attack against them and fired back.

Coalition officials consider the Frontier Corps’ behavior irresponsibly dangerous considering that NATO interpreted the existing rules of engagement as allowing coalition forces in cases of self-defense to engage targets across the border without seeking advanced permission. DoD Spokesman Geoff Morrell stressed that American troops retain the inherent right to self-defense wherever they are deployed. “And remember… we will retain the right to defend our forces, to defend ourselves. And our forces who operate on the border with Pakistan are in a very dangerous and difficult situation.”

In Kabul, NATO staff criticized the border guards’ decision to fire at the helicopters rather than use established procedures to protest the border overflight, while in Washington, defense officials wondered why the Pakistanis did not simply try to communicate with NATO by car or radio.

U.S. officials initially resisted apologizing for the incident or offering to pay compensation to the victims’ relatives since those killed had opened fire first on U.S. forces. NATO invited Pakistani military representatives to participate in a joint investigation of the cross-border incident. They also offered them access to the video tapes made by the helicopter’s onboard cameras to demonstrate that the crew had acted in self-defense.

But the Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs felt compelled on this occasion to call these overt border violations and attacks on its territory a “clear violation and breach of the UN mandate,” which authorized ISAF combat operations only in Afghanistan. Interior Minister Rehman Malik said that an investigation was needed to assess the reasons for the attack, in effect to determine in NATO eyes “whether we are allies or enemies.”

Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani told members of Pakistan’s National Assembly that his government would defend Pakistani national sovereignty at all costs: “We can never allow you [NATO] to infringe on Pakistan’s sovereignty and security. And if you will not explain your actions, compensate us and apologize for this, we can use other means. And we have other options.”

More importantly, the Pakistani officials denied that agreed rules of engagement existed that permitted coalition forces to attack and even enter Pakistani territory in response to insurgent threats. A Foreign Ministry statement insisted that, “there are no agreed ‘hot pursuit’ rules” and that, “Such violations are unacceptable.”

In addition to the rhetorical flourishes, the Pakistani government closed the Torkham Gate at the Afghan border for more than a week. Simultaneously, various groups of militants, perhaps with the complicity of the local Pakistani authorities, torched dozen of the oil tankers and other vehicles at various locations in Pakistan that were conveying supplies to ISAF. But Pakistani officials kept other logistics routes, including the Chaman crossing, open to the NATO conoys.

Pakistan’s civilian government is in a different situation.

Its members must show Pakistani nationalists that they are not American lackeys and will resist Washington’s pressure. The return to a democratic regime in Pakistan has made it more difficult for the government to pursue Musharraf’s policy of simply ignoring popular views. Pakistanis note that whatever consent Musharraf gave lapsed with his retirement and the end of military rule. Pakistani civilians generally resent these bilateral defense ties since they perceive Americans as having endorsed their military government and as having sought to use the Pakistani army as a mercenary force to fight for Washington. Pakistani public opinion is clearly hostile to the United States, in general, and U.S. military operations within their country, in particular.

Pakistanis widely blame the U.S. war against the Taliban and other Muslim militants for bringing terrorism to Pakistan, which has suffered from suicide bombings and other civil strife in recent years. Pakistanis calculate that they have incurred enormous financial losses and other costs in terms of the elevated terrorist violence Pakistan has experienced since Islamabad’s decisions to side with Washington and support the U.S.-led Operation Enduring Freedom after 9/11. They note that the Pakistani armed forces have suffered more casualties fighting Islamist militants than have coalition forces on the other sided of the Afghan-Pakistan border.

They see the increased U.S. drone and cross-border attacks of recent years as a form of coercive pressure to force the Pakistani government to crack down on the Taliban militants based in the tribal areas, which would further increase Pakistani military causalities and terrorist victims.

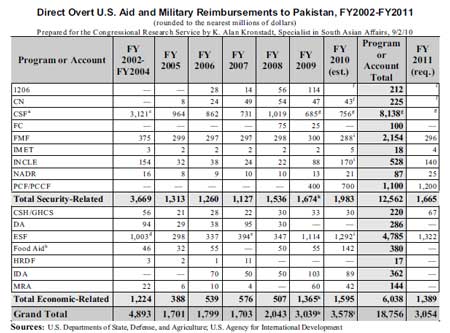

But Pakistan receives billions of dollars of assistance from the United States— originally focused on security assistance but increasingly encompassing nonmilitary aid as well—and the civilian government is genuinely opposed to terrorism. Breaking with the United States and NATO would benefit India in the diplomatic competition between the two nations.

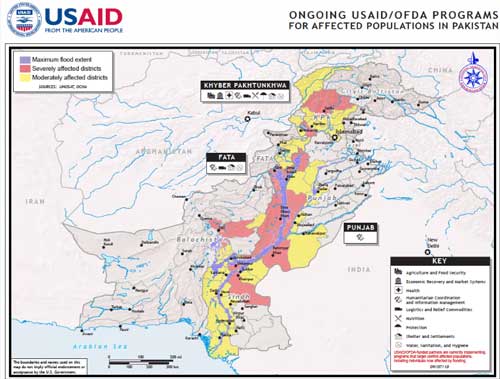

USAID Pakistan Flood Relief (Credit: http://www.usaid.gov/pk/)

USAID Pakistan Flood Relief (Credit: http://www.usaid.gov/pk/)

Pakistani officials have sought to limit U.S. military operations in their country by affirming their commitment to reign in extremist activity in Pakistan and across the border. The Pakistani army has also resumed military operations against the Pakistani Taliban, though the recent floods have disrupted whatever intent it had to expand operations throughout the remaining tribal areas.

Despite the government’s formal opposition to the drone attacks, it is understood that the UAVs operate within Pakistan with that government’s approval and reportedly with its intelligence assistance—vitally important given the limited U.S. human assets in the region—now that the drones target the Pakistani Taliban as well.

From the perspective of the Pakistani government, the problem with the recent helicopter attacks was that they deviated from the standard rules of engagement as well as the attacks having led to the deaths of three Pakistani soldiers. Pakistani authorities regularly overlook the occasionally firing of a helicopter missile across the border, even the temporary overflight of the copter across the imprecise Afghan-Pakistan border, as long as the incident does not attract much public attention.

They even rapidly overcame the negative fallout from the June 2008 incident in which an ISAF air strike killed 11 Frontier Corps members manning a border checkpoint, leading to an exchange of fire with other Pakistani forces.

But in late September, at the same time that the CIA was launching a record number of drone attacks on Pakistani territory, U.S. helicopters fired missiles into Pakistani territory four times within one week and spoke about the attacks in public. Pakistani officials originally said nothing about the September 24 and 25 helicopter missile strikes on Pakistani territory, but the September 30 attack killed three paramilitary soldiers located inside Pakistan, making it hard to conceal. One of the cross-border helicopter attacks that occurred a few days before the attack on the Frontier Corps members killed as many as 60 fighters who had been attacking an Afghan border post but by the time they were hit had fled to the Pakistani side of the border.

Rather than remain silent, moreover, NATO officials confirmed the media reports that its manned helicopters had on crossed into Pakistani territory and killed Pakistanis located there, actions that alliance representatives justified as legitimate acts of self-defense.

In the end, NATO officials decided to resolve the crisis by issuing various forms of regret and apologies. ISAF Commander Gen. David Petraeus, who also leads the U.S. Command in Afghanistan, and Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the U.S. Joint Chefs of Staff, called the head of the Pakistani military, Gen. Ashfaq Kayani, and conveyed his grief over the three deaths. NATO Secretary General Rasmussen “expressed my regret for the incident last week in which Pakistani soldiers lost their lives, and my condolences to the families.

Obviously, it was unintended. Obviously, we have to make sure we improve coordination between our militaries and our Pakistani partners.” Senator John Kerry, one of Pakistan’s staunchest supporters in Congress, spoke with Prime Minister Gilani to help restore ties.

One factor helping to change the Pakistani position was the mysterious emergence at this time of a video depicting the illegal executions of six blindfolded young men by people dressed in Pakistani Army uniforms. The crime threatened to weaken support within Congress for providing further arms and other military assistance to Pakistan. The Pakistani authorities soon claimed to have identified the soldiers involved and indicated they would be punished.

Despite the apologies and reopening of the border crossing on October 10, the incident came at an unfortunate time in that relationship between the United States and Pakistan, which had been on the upswing in the months following a highly successful meeting in Washington between U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi for their July 2010 U.S.-Pakistan Strategic Dialogue.

By early October, frustrated American officials were worrying that the incident has negated whatever goodwill the United States achieved by enacting billions of dollars in aid, including a five-year $7.5 billion civilian aid package aimed to show that Washington wanted a long-term non-military commitment to Pakistan extending beyond the war on terror, and in having the U.S. military assume such a visible role in assisting the Pakistani authorities manage flood relief. The U.S. government spent more than $100 million on Pakistani flood relief partly, as Morrell noted, for “enhancing our reputation and our image in Pakistan.”

They also fear the damage, seen as self-inflicted in Washington, the Pakistani civilian government has incurred from the incident, which follows other problems including a highly criticized response to the floods, continued allegations of corruption, and weak economic performance.

State Department spokesman Philip Crowley stressed that, while seeking to maintain dialogue and good ties with the Pakistani military, the United States was “working with Pakistan to increase the capacity of this government, the performance of this government. It will be important for a civilian government to demonstrate its value to the Pakistani people. The Pakistani people have made clear that they prefer civilian government to dictatorship.”

Fortunately, few analysts believe the military wants to retake political power. On the one hand, it would not want to assume direct responsibility for the current crises besetting Pakistan. On the other hand, the current civilian government has effectively given the military whatever it wants, including vast resources and considerable autonomy to conduct its military operations as it sees fit, including some unwelcome to the United States and its allies.

Still, Afghan-Pakistan border tensions are likely to recur—and worsen—as NATO troops withdraw from Afghanistan. Western governments will increase their pressure on Pakistani authorities to prevent the Taliban from exploiting the vacuum, but Pakistani leaders will want to hedge against the Taliban’s regaining control of some if not all their border regions.

They will seek at a minimum to avoid antagonizing it—and at least certain Pakistani national security managers will invariably be tempted to revise old ties and use the Afghan Taliban as an instrument for asserting Pakistani influence in this important neighboring country while also countering Indian influence there.