An Interview with Senior Master Sgt. Steven Wehrle and Master Sgt. David Freeman

11/05/2010 – In September 2010, Second Line of Defense sat down with maintainers at Langley AFB to talk about F-22 experiences and preparation for the F-35. As the maintainers described it, a significant cultural change was underway which would leave to significant manpower savings and enhanced supply chain efficiencies. Senior Master Sgt. Steven Wehrle and Master Sgt. David Freeman of the USAF provide their judgments on evolving experience with 5th generation aircraft maintenance approaches.

***

- “I started out on U-2’s many years ago, which is one of our most primitive planes still in inventory.” (Master Sergeant Freeman) (Credit photo: 380th Air Expeditionary Wing, 0 3/09/2010)

SLD: What are some of the challenges in preparing for the introduction of the F-35 at Langley AFB, from a maintenance point of view?

Senior Master Sgt. Steven Wehrle: My worries are not focused on the brand new one-striper coming out onto the ramp to crew an F-35; he’s going to get trained. The Air Force rightfully so puts a lot of time into its young troops upfront to ensure they are ready to execute the mission. What we are very concerned about is the Senior Airmen that crewed F-16s, or F-15s, and is transitioning to the F-35. What I’m referring to is a mindset change in our sustainment practices.

We have to ensure we are effectively preparing our mid-level Airmen and our logistics supervision that are transitioning to the F-35. The acquisition and sustainment of this platform is wholly different than anything that has been done before. This is not just an exclusive Air Force platform and Air Force buy, there will be many processes and procedures executed differently. It is a joint platform where commonality and affordability have driven concessions amongst all.

SLD: One of the challenges clearly is to leverage the commonality provided by the maintenance systems and interact with service cultures in shaping effective maintenance approaches. Also, I have seen with regard to the Osprey that there is a challenge as the most experienced maintainers are used more to mechanical than digital systems, and there will be a transition. Is that part of what you are talking about here?

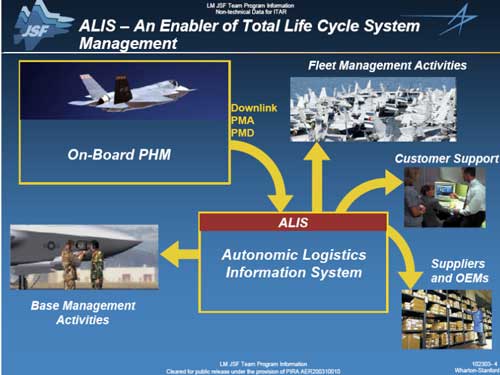

Senior Master Sgt. StevenWehrle: Yes you are right. The Autonomic Logistics Information System or ALIS is at the heart of this new air system. It is a challenge at first getting folks to accept this paradigm shift in technology. ALIS is much different in that there are a number of things—like I had mentioned earlier—that are designed to meet the joint or common solution. Because of the common solution challenges are bound to arise that make us reevaluate our legacy processes.

(Credit: http://opim.wharton.upenn.edu)

(Credit: http://opim.wharton.upenn.edu)

SLD: You are describing the need for a culture change and to anticipate the time necessary to make that crossover to the new approach?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: It’s a completely different mindset; it’s almost like what our operators are saying. You have to shift. I started out on U-2’s many years ago, which is one of our most primitive planes still in inventory. There are no hydraulic actuators to assist the flight controls. Cables, bell-cranks and pulleys that must be hand rigged are used. So that’s the technology level I started on. Mechanical ability was crucial to performing maintenance.

As a Senior Airman I moved to a little more high tech platform, I moved up to the A-10. I went from 50’s technology to 70’s technology. So, I went little bit up in the evolution chain to the A-10, great plane, easy to maintain, I liked it.

Later in my career I transitioned over to the F-22, which was a big jump, going from analog to digital—you’re still turning bolts, you’re still turning wrenches, but the way everything is put together and fused on the ops side drives a whole new requirement for all the electronics, pieces and bits that are put together. It’s maintained in a completely different way. You don’t rig flight controls on an F-22 or an F-35; well, you do but you do it with a laptop and a keyboard versus a tensiometer.

Many legacy organizations within maintenance are going to fade away on the flight-line. There are reasons these organizations and tools are going away. They’re just not needed anymore, because there are not those previous maintenance activities occurring. Many tasks are done so easily now on a computer, or via a bit check. Computers are taking over the workload just like they’re taking that workload off the pilot.

SLD: This cultural shift that you are describing has started with the F-22 maintenance experience?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: It has. With the new guys when they come out to learn F-22 maintenance, this is normal for them. The challenge arises when you try and take the old guys or even the middle level personnel, who are used to using paper manuals to do repairs, or go look at a fault isolation blueprint. Those don’t even exist in modern fifth gen. You have to rely on the prognostics and diagnostic systems on the plane to tell you what’s wrong. When we previously did troubleshooting, we built fault trees and trouble trees. With 5th gen we rely on the computer diagnostics and the air system’s prognostics.

The migration will be difficult moving from the analog to digital for the older guys. And it’s going to be, but as we move into the future, into the iPad/iPod generation, the young guys that are coming out and learning this stuff, it’s going to be second nature to them.

These tools are going to be very valuable to the older maintainers as well, it’s just such a leap, and I imagine maybe even in the pilot community you’ve had some of these challenges with older pilots who are used to older aircraft as well. I’m sure they went through the same thing.

(Credit: http://www.asipcon.com)

(Credit: http://www.asipcon.com)

SLD: But I’d like to go back to the F-22 maintenance regime versus the F-15. How is that different?

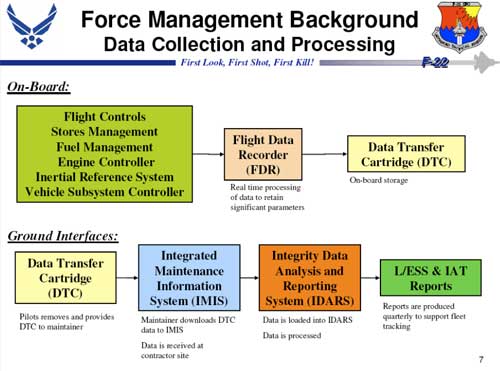

Master Sgt. David Freeman: The F-22 will tell you what the fault is through the ICAWs, integrated caution and warning system. ICAW. And the jet will tell you hey, I’ve got an advisory going on with this system, or hey, I’ve really got an emergency, you’ve got engine fire, and it puts out the fire before you even have time to hit the buttons and turn it off.

And the Eagle, it was the mindset of it was just a big system, and I have to manage an emergency and I have to know to go over here and I know the indication is going to be this and this gauge, and back over here. And I’m going to have to do some troubleshooting.

Whereas on an F-22, the majority of the emergencies or faults that we have are reported by the aircraft. Or sometimes they’re not even shown to the pilot until we get to maintenance debrief.

Whereas in the F-15, you just indicate that I flew today, I got this light and that means it’s broken or you guys need to take it from here and fix it. The F-22, I might have that fault, it does its own analysis.

But then when I’m done with the aircraft, I bring in my digital transfer cartridge, it’s basically about the size of one of your recorders there. I plug it into the computer and then the maintenance system downloads all the faults that the jet is reporting everything.

On the F-22, everything is integrated. So I might lose this electrical system or this vehicle control node, and it has fingers in everything.

SLD: Could you describe the difference between maintenance on the F-22 and the F-15?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: You’re shifting from a reactionary maintenance regime in a legacy plane to a proactive and targeted maintenance regime in 5th generation. If you look at an F-15 or F-18, you don’t fix anything until it breaks; until the component is broken, there was very little prognostic type indications to tell you this may break in the future. So we built in a redundancy and we built in schedule maintenance regimes where you inspect things every so many hours.

With the technology that’s coming along you leverage the sensors, this is nothing new and fancy; look at cars. I mean, you look at a car from the 80s, how do you change your oil? You change your oil every 3,000 miles or every three months. Any new vehicle that’s out anymore has a sensor. The computer tells you, change your oil.

It’s the exact same technology that’s being applied now that has been to the F-22 and the F-35 and even the F-16 to shift from reactionary maintenance regimes to more prognostic maintenance regimes where you can begin to predict reliably to lean your logistics chain down to support realistically your operations.

SLD: So leaning down your logistic chain is a big gain for your maintenance regime?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: You’re not over-inspecting is one advantage. You’re not overstocking parts that you may not need. You can begin to really focus your logistics effort by analyzing data 5th gen fighters are designed to utilize.

On the F-35, the data file that comes off the jet is gigantic. It records everything that’s happening on the jet and it goes into a file. Over time, we are going to shape how we use the data generated by the plane to get really effective maintenance metrics.

SLD: You are underscoring that the data advantages of the F-35 will be leveraged over time, will take time to leverage, but will build long-term advantages for a maintenance regime?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: The ALIS system that they have built and the whole autonomic logistics construct for the F-35 is going to be awesome. Previously, we had many barriers in legacy sustainment of the planes, where there are many federated things in your supply chain. But with a single supply chain driven by an integrated aircraft, a lean approach is possible. The guy on the flight line doesn’t care where his parts come from as long as he can get them.

SLD: Your point about the federated system is you have several un-integrated elements, each with its own maintenance and supply chain?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: Absolutely. I don’t care where that part’s coming from, as long as when my plane breaks, if I can get a part tomorrow and I don’t have to pull it off the plane sitting beside it to get that replenished, I don’t care. If it comes from the US or any partner nation, I don’t care. As long as it’s a reliable part that lasts, meets my specifications and standards and I can get it tomorrow, I’ll take it.

SLD: How will the ALIS system work for you?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: It’s very simple. While you’re doing your job and you’re doing your maintenance, you tick a box. That’s all you do to order a part. It’s all shot out instantly electronically

That’s all within ALIS. When I first saw it I was shocked. I thought, “Do the supply guys know about this? That all I have to do is tick a box and a part is coming my way”? Normally, I have to fill out a form that is a page and a half long just to get a screw or something very simple.

In ALIS, all you do is tick a box, and it’s intuitive enough to pull in your part numbers, all that data that it needs to, it already knows, it’s already in the system. So you tick the box, the requisition goes over to the supply module of ALIS. The system responds letting me know if I have this part in my local warehouse. If it’s in the local warehouse, it sends me back a message saying it’s ready for pick-up, come and get it.

If it is not locally sourced, it goes out to regional supply and you’ll get a message back within a certain time period of where that availability is and when you’re going to get it. Then all these mechanized processes, which are automatically done in the background, are checked and of course there’s supply oversight into the process. It’s much more mechanized and automated in the background in ALIS versus legacy systems.

SLD: What has been the reaction to other maintainers when they see the new approach?

Master Sgt. David Freeman: Lockheed Martin hosted a conference over at the Center for Innovation near here in Suffolk; it was about a month ago, a little over a month ago. They invited our HQ ACC/A4 counterparts to come over with their weapon system teams to see the flight-line of the future. The F-22, F-15, F-16 and A-10 weapon systems teams came along. They were able to see ALIS, to see how it was going to work, including the future of maintenance on the F-35.

Every single one of those maintainers that I talked to you, their jaws just dropped. They all said, this is awesome, and I want this for my platform. I want this for my plane. If you can make it work, I want it. A great example was the A-10 weapons team superintendent, I was talking to him, he said he could call DLA right now and asks them how many of these widgets do I have in supply? Then if he were to call back the next day he gets several answers, usually different answers.

All of the legacy teams expressed frustration with an ailing defense supply chain that continues to have challenges keeping their planes in the air. Many echoed “Legacy has grown too large and complex relying on vendors that are no longer even in business to source parts on our aging fleet.”