United States Is On The Verge Of Losing Its Aerospace Industry, Analyst Warns

By Richard McCormack

This article was originally published in Manufacturing & Technology News on September 30th, 2010. All graphs come from: “A Case for Repayable Launch Aid,” a study by David Pritchard

***

11/05/2010 – The U.S. aerospace supply industry is on the cusp of extinction if the United States government does not put into place a set of industrial policies aimed at making sure it survives an onslaught of foreign government- backed competition. As foreign nations promote the rapid development their own large-body aircraft production industries, U.S. companies risk not being part of any of those international supply chains.

Adding to the woes of U.S. suppliers is the business model adopted by Boeing of shifting the production of parts, components of subsystems to foreign companies. “This is a here-and-now moment” for the United States aerospace supply sector, says David Pritchard, a long-time aerospace analyst with the Canada-United States Trade Center at the State University of New York in Buffalo.

If the United States government does not get engaged in a manner similar to what is occurring over-seas, then it will have to accept the fact that the country’s most important export industry will no longer be a driver in the U.S. economy. Employment in the U.S. aero- space sector has taken a nose-dive, from 1,331,000 in 1989 to 657,000 in 2008. Canada, China, Russia, Brazil and Europe are all developing a new generation of large commercial aircraft. These countries “are putting billions of dollars into their aircraft industries because they say it’s in their national that we have to play by our own rules and that we’re going to be different,” Pritchard explains.

The perception that U.S. historical dominance will persist is causing great damage to the industry, according to Pritchard. “We need to help our suppliers be competitive globally otherwise they are not going to be around.” Foreign countries have explicit industrial policies aimed at promoting the development of their aerospace manufacturing processes and technologies. To sell into those markets, U.S. aerospace companies have been required to participate in those industrial policies, by transferring technology and production under “offset” agreements. “While these strategies may be commercially successful in the short term, they undermine the long-term interest of the U.S. manufacturing infrastructure, American workers and ultimately the U.S. position in this strategic industry,” according to Pritchard. Foreign ownership, production and technology transfer requirements have shifted manufacturing technology, engineering data, product processes and managerial talent offshore.

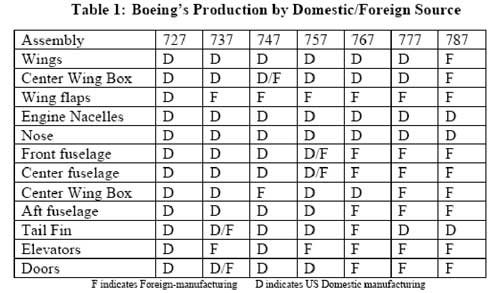

Moreover, Boeing has been placing the burden of re-search and development onto its suppliers. Instead of investing in research into new production and manpower systems, the company instead has spent $20 billion over the past 20 years buying back its stock. The re-search and development function has been shifted mostly to its foreign suppliers who receive financial assistance from their host governments. The foreign content on airframe structures for the Boeing 787 Dreamliner was 90 percent, Pritchard notes. Almost 70 percent of the 787 is being manufactured offshore, with assembly in the United States accounting for 4 percent of the total value of the aircraft. Pritchard estimates that imports of parts and components account for 60 cents of every dollar of aerospace exports, up from 40 cents in 2000 and 11 cents in 1970. “It’s great that you have an export going out, but how much foreign content is involved in the export?” he asks. “Nobody talks about it.”

Boeing has been placing the burden of re-search and development onto its suppliers. Instead of investing in research into new production and manpower systems, the company instead has spent $20 billion over the past 20 years buying back its stock. The re-search and development function has been shifted mostly to its foreign suppliers who receive financial assistance from their host governments. The foreign content on airframe structures for the Boeing 787 Dreamliner was 90 percent, Pritchard notes. Almost 70 percent of the 787 is being manufactured offshore, with assembly in the United States accounting for 4 percent of the total value of the aircraft. Pritchard estimates that imports of parts and components account for 60 cents of every dollar of aerospace exports, up from 40 cents in 2000 and 11 cents in 1970. “It’s great that you have an export going out, but how much foreign content is involved in the export?” he asks. “Nobody talks about it.”

According to Pritchard’s analysis, Boeing had originally outsourced over 90 percent of the parts for the 787, “even after the U.S. government provided Boeing with $1.8 billion in NASA money for the High Speed Civil Transport program which was earmarked to develop the U.S. industrial base,” he writes in a new study. “The U.S. taxpayers reward Boeing shareholders with billions of dollars by elimination of taxes, yet there is no accounting for domestic content in return. For the first time in U.S. commercial aviation history, foreign risk-sharing partners will have control over the selection of second-and- third-tier suppliers.”

Since 2001, Boeing’s workforce has been downsized from 90,000 to 64,000. If American companies do not start supplying new foreign aircraft programs, their global market share “will continue to deteriorate,” writes Pritchard. “The smaller second- and third-tier suppliers are not typically flush with capital to invest into new aircraft programs which could force them to merge with other U.S. suppliers, be sold off to foreign competitors or exit the market.

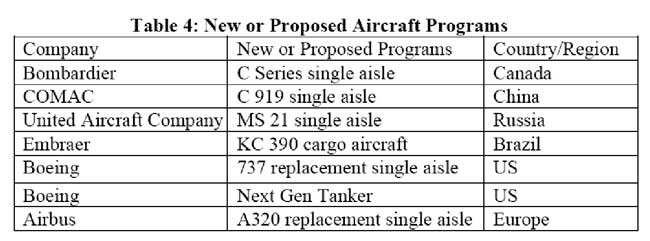

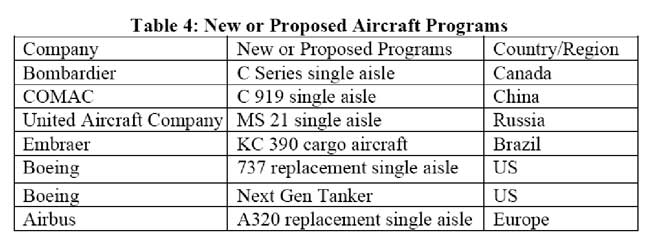

The next five years will be a critical time for the U.S. commercial supply chain on what decisions will be made for its future competitiveness.” A new global competitive structure is quickly unfolding, displacing the dominance held by Boeing and Air- bus. In 2008, China created the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC) to develop a single aisle commercial airliner – the C919 – that will compete directly against Boeing’s 737 and Airbus’s A-320. COMAC is also developing a regional aircraft, the ARJ 21. In order to provide COMAC with hardware systems, foreign suppliers have been required to form joint ventures with majority ownership held by Chinese partners.

Over the past 30 years, through similar technology transfer and production requirements, China has acquired “the full capability for producing aircraft that would meet U.S. Federal Aviation Administration certification standards,” says Pritchard. In what Pritchard describes as a dumb economic policy, President Obama said he would help the Chinese get the ARJ-21 certified by the FAA. Obama made the pledge on a visit to China last November. “You don’t just give the golden keys of technology to them,” says Pritchard. “Once you get FAA certification, it’s a validation to sell worldwide and [the aircraft] is accepted. I just don’t understand why you would want to do that. You know China is subsidizing its aircraft industry and yet you don’t do anything about it and, by the way, the President is going to help you. There is a disconnect here.”

Over the past 30 years, through similar technology transfer and production requirements, China has acquired “the full capability for producing aircraft that would meet U.S. Federal Aviation Administration certification standards,” says Pritchard. In what Pritchard describes as a dumb economic policy, President Obama said he would help the Chinese get the ARJ-21 certified by the FAA. Obama made the pledge on a visit to China last November. “You don’t just give the golden keys of technology to them,” says Pritchard. “Once you get FAA certification, it’s a validation to sell worldwide and [the aircraft] is accepted. I just don’t understand why you would want to do that. You know China is subsidizing its aircraft industry and yet you don’t do anything about it and, by the way, the President is going to help you. There is a disconnect here.”

The United States is stuck in the mentality that it is the world’s dominant economy with the best technology. “The playing field has shifted and we want to act like we’re in the 1950’s with all the ability to wield our economic power.” That is no longer the case and such thinking is proving to be economically damaging. China especially has been successfully implementing a vigorous 20-year strategy to develop its commercial aircraft industry with government funding. “If you sit there and say that isn’t fair, it means you have your U.S. hat on again,” says Pritchard. “Look at it from the Chinese viewpoint. Why should they keep buying western airplanes from Boeing and Airbus? Why don’t they develop their own industry? Even if they supply their only own market for the first 20 years, there is demand for 3,800 single aisle airplanes that will keep them busy for the next 10 or 15 years just by themselves.”

Even a country like Mexico has been growing its aerospace sector. There are now 27,000 aerospace workers in Mexico. “Where did they come from?” Pritchard asks. “What are the reasons to set up aerospace suppliers in Mexico? Skilled labor? No, they don’t have any skilled labor. Supplier cluster infrastructure? No, they don’t have a supply infrastructure? Any natural resources you need to have? No. There is nothing there to have an aerospace cluster other than a company’s desire to take lower end work there and now they are moving up the chain.

Even a country like Mexico has been growing its aerospace sector. There are now 27,000 aerospace workers in Mexico. “Where did they come from?” Pritchard asks. “What are the reasons to set up aerospace suppliers in Mexico? Skilled labor? No, they don’t have any skilled labor. Supplier cluster infrastructure? No, they don’t have a supply infrastructure? Any natural resources you need to have? No. There is nothing there to have an aerospace cluster other than a company’s desire to take lower end work there and now they are moving up the chain.

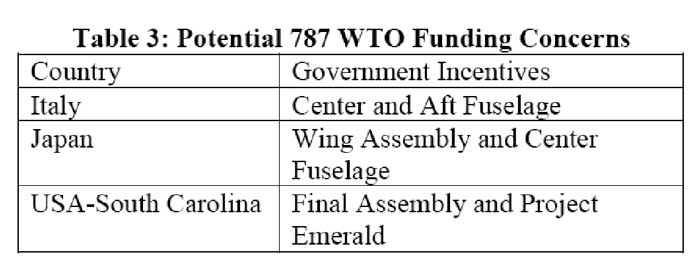

And once it is outsourced, it never comes back.” To reverse the outsourcing and importing trends, and encourage American commercial aircraft suppliers to be- come active in the global supply chain, Pritchard says the U.S. government needs to adopt an industrial policy that focuses on “repayable launch aid.” This aid “could be similar to the terms of the 1992 EU-U.S. Large Aircraft Agreement that includes limited direct government sup- port to 33 percent of development costs; support given to programs likely to repay the loan in 17 years; and re- payments that are based on a per-plane basis rather than at the end of the loan,” Pritchard writes. “The main advantage for the U.S. government support to its commercial aircraft suppliers with repayable launch aid is that the U.S. could receive back royalties which could exceed the loans given to the suppliers.

This is in contrast to current governments’ support of tax incentives being given to the industry which are never paid back.” This is especially important now that the WTO is expected to rule that many of the incentives provided to Boeing by the federal, state and local governments have been illegal subsidies. The ruling will likely have ramifications for other industries in the United States that are being subsidized by taxpayers. Even the government bailout of GM could be considered an illegal WTO subsidy.

“Great, Boeing won the battle over Airbus and U.S. industry lost the war,” says Pritchard. “Does that case open the door to more filings against U.S. companies? It’s too early to say, but we need to look at the big picture here before we start attacking the rest of the world.” There is little chance that the U.S. government will confront China over its aerospace industrial policies “because it would be suicide for other industries that work with China,” he says. “It could be argued that the market should pick the winners and losers, [but] with the presence of foreign governments pumping billions of dollars into their commercial aircraft industries, the success for the U.S. commercial aircraft supply chain hinges in large part of the U.S. government moving to an industrial policy.”