01/04 /2011 – In a sidebar conversation to the presentation of Lt. General Deptula’s briefing on the PLA Air Force, Second Line of Defense’s Robbin Laird discussed with Lt. General Deptula ways to think about the evolving Chinese challenge.

China’s Yilong UAV Credit: www.china-defense-mashup.com

R. Laird: Why don’t we talk more generally about the PRC challenge, because from my point of view, probably the best way to understand these folks is how they’re building an air space industry, both military and civilian? This should be viewed as a strategic objective, and so they’ll be challenging A320s and 737s in the commercial marketplace, as they’re going to challenge us in the military marketplace. And I think both are viewed quite similarly and with the same industrial base virtually. Secondly, I think folks need to understand the Chinese pursuit of innovation. They are building UAVs, missiles and will come up with different answers than we’ve historically done. Often, when people think about the PRC, they’re thinking of 30 years of following our pathway, and then one day they wake up and they’re a power. They’ve already demonstrated in the commercial domain their quick closing capabilities. The third broad point is that there’s a significant focus in taking away advantages that we’ve historically had in air power. So you develop missiles to make it take out AWACS. They’re studying our historic operations and are looking for our weaknesses and are trying to exploit those things. Do those three broad propositions that make sense to you?

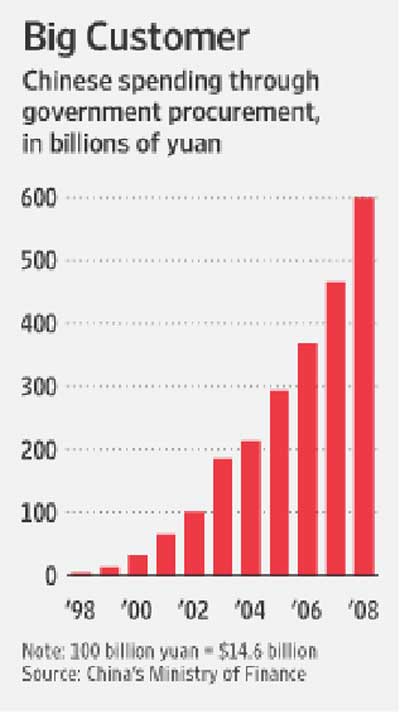

Lt. General Deptula: They do, and the ability of the Chinese to accelerate innovation in the air domain is quite impressive. They now have the ability to make major investments with the monies that are available from their economic growth for continued investment in research and development. That growth in the Chinese economy allows for investment in innovation. Unfortunately, until recently little concern has been evidenced by senior US defense leadership regarding the strategic challenges posed by the Chinese. How much investment is China making in advanced research and development vis-à-vis what the United States is doing? That will tell you how rapidly China will be able to accelerate in terms of military capability at a period in time where the United States is throttling back in terms of military capability.

A recent article in the Shanghai Daily stated that “CHINA is set to become the world’s most important center for innovation by 2020, overtaking both the United States and Japan…” That’s another piece that you hit on in the context of: “Look, this isn’t just about the military piece; there’s also another element with respect to aerospace.” The space piece is increasingly important as well. They’re becoming well aware of the importance of being able to dominate an air and space. “The shift is not because the US is doing less science and technology, but because countries like China and India are doing more research. China is now the second-largest producer of scientific papers after the US, and research and development spending by Asian nations in 2008 was US$387 billion, compared with US$384 billion in the US and US$280 billion in Europe.”

China used to view the United States as the gold standard for which to aspire to in terms of military capability to emulate. Now they’re specifically targeting how to disable or negate what used to be U.S. advantages. From their perspective it’s becoming increasingly easier and easier to do that as the current U.S. Department of Defense leadership has elected to focus on the present to a much greater degree than the future.

R. Laird: And I think the real problem on the U.S. and European side, the same thing, is we’re kind of stopped. We seem to think we can rest here while something good happens, and that’s part of the problem.

Lt. General Deptula: Right. Simply put, there is a group-think that has captured the security elite that since we’ve been dominant in conventional warfare over the past quarter-century, we’ll remain so in the future. It’s a convenient presumption given the current economic environment, but a very dangerous one. It may play to conventional wisdom to state that the biggest threat to defense is the deficit, and while partially accurate, the immutable nature of conflict—and deterrence—is more basic—strength wins over weakness. As one looks to the future—given the current investment path the United States is on—the United States and our allies are becoming weaker.

The difficult position to take—given the current economic conditions and nation-building engagements we have elected to pursue—is to articulate the kind of investments we need to make in defense to secure a position of strength in the next quarter-century.

R. Laird: The Chinese have already reached out into the world and affected our military behavior. The carrier task force that was either withdrawn or not deployed in an exercise is a basic factoid as perceived in Asia.

Lt. General Deptula: The problem is when you send force to be symbolic, you better have sufficient wherewithal to back up your move with actual force application that your potential opponents know would be devastating, otherwise the “signal” is not going to be effective. The Chinese have told us to “pound sand” with respect to our recent “signals” regarding North Korean actions, and they will continue to do so as long as we speak with hollow words. As reported by Philip Ewing recently “Chinese officials responded to two days’ worth of [the US Chairman of the Joint Chief’s of Staff] condemnations by doubling down on their support for North Korea; top diplomat Dai Bingguo took presents to Kim Jong-il and “greetings” from Chinese president Hu Jintao. The response showed that the Obama strategy of increased pressure is at least getting to China and the North – although not producing the effect the U.S. wants.” I think your real point is: We don’t have the dominant capability that results in a real determinant that moving force in the region would actually demonstrate—or as raised by Michael Auslin recently in his piece “The F-22: Raptor or Albatross,” the current defense leadership may not be deploying its most capable system due to concern that doing so may illuminate the value of investing in them, thereby uncovering their error in judgment in terminating investment in what brings the U.S. its asymmetric advantage.

R. Laird: But I think the broad problem we have is that folks assume a dominance we don’t have; they still think strategically as if they had it. So they don’t understand you can’t do shadow boxing when I can’t bring the determinant crushing blow with you.

Lt. General Deptula: The Chinese used to have vast quantities of airplanes that were not qualitatively that good. Well, now they’re transitioning very rapidly from quantity to a qualitative force and transforming their old fighters into remotely piloted aircraft with sufficient quantities and in a mix that will pose a very complex military challenge across the board.

R. Laird: The issue here is as well the ability of the US to provide the linchpin force for our Asian allies. It is not like the Soviet-US competition in Europe where we had to prepare to occupy Russian territory as part of deterrence. With China we seek to deny their ability to reach beyond their littoral waters. We seek to have air and naval assets, which our allies can rely upon to augment their own and shape a significant curtailment capability. So our challenge, from my point of view, has always been: I don’t have to destroy the Chinese way of life, but I certainly have to be able to destroy every military asset that comes out into the South China Sea. It’s very simple. I need to curtail them. I don’t even have to contain them, but I need to curtail them to such a significant extent that Singapore, Australia, and others believe in our ability to be a linchpin to help them curtail the Chinese and put them back into the mainland. And I can only do that with air and naval power.

Credit: www.defense.gov

Lt. General Deptula: And that’s what an effective conventional deterrent strategy would do. Unfortunately, if we have one, it’s not very clear to friends and allies, much less those we are trying to deter, and how it fits into a grand strategy is even less evident. Our allies our very aware of the trends we’ve been discussing here. So much so that those trends are already significantly affecting their strategy and decision-making processes. All you need to do is look at the 2009 Australian Defense White Paper—here they are pretty blunt about it in terms of questioning whether or not they can continue to count on the United States in her role of traditional ally to maintain a deterrent capability. When I say “deterrent,” I mean a viable deterrent force to do the kinds of things that you’re talking about—to deter the Chinese from any notion of adventurism outside their borders.

R. Laird: We’re talking about a linchpin force that can work with the allies, certainly smaller than a force that would have invaded the Soviet Union and destroyed through eleven time zones. We’re talking about a force that’s an adequate, dispersed, viable linchpin that can work with allies. It’s much smaller than the one we had parked up against the Warsaw Pact, but it has to be more advanced, not less advanced.

Lt. General Deptula: We have to build a force to present a complex set of challenges that are so disconcerting to potential adversaries that they wouldn’t even consider taking it on because of fear of failure.

We have to build a force to present a complex set of challenges that are so disconcerting to potential adversaries that they wouldn’t even consider taking it on because of fear of failure.

—-

For an earlier conversation on the Chinese challenge see our interview with Mark Lewis.