The United States and the Arctic

By Rear Admiral Jeffrey M. Garrett, U.S. Coast Guard (Retired)

07/07/2011 – Long relegated to the periphery of world affairs—occupying the distorted top edge of a conventional Mercator projection of the world—the Arctic has been rediscovered in the first decade of the new millennium.

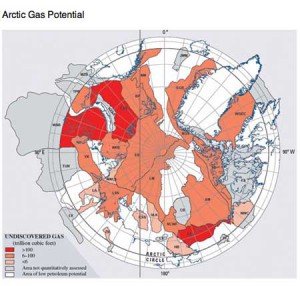

The diminished summer ice coverage has opened the Arctic to an unprecedented level of resource development activities, increasing maritime surface transportation, a surge of tourism and adventure travellers, and, of course, evolving political, defense and security issues.

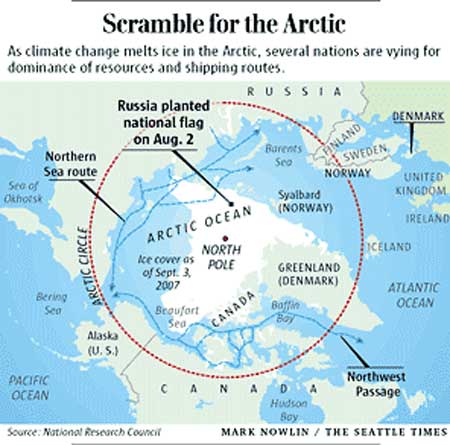

In an echo from an earlier age, the Russians dramatically planted a titanium flag on the Arctic Ocean sea bottom, at the pole, in the summer of 2007. Although the explorers used the robotic arm of a mini-sub, rather than planting a banner on a sandy beach, this event has unleashed a steady stream of media attention on the Arctic’s future prospects in a world growing ever more connected and hungrier for resources.

In recent months Second Line of Defense has examined many of these Arctic issues, notably in Caroline Mükusch excellent four-part series on this site. In her review of the U.S. role in a transforming Arctic, Ms. Mükusch labels the United States “a reluctant Arctic power.” It is an apt characterization.

U.S. Arctic Policy

True, the U.S. has not completely ignored its role as one of the five nations positioned on the Arctic Ocean waterfront. In the waning days of the George W. Bush administration, the President signed National Security Presidential Directive 66/Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25 (NSPD-66/HSPD-25), entitled Arctic Region Policy.

This policy statement was reviewed and accepted by the incoming administration of Barack Obama. It lays out security, environmental, economic, cooperation and science goals for the U.S., and in their implementation directs the executive branch to:

- Develop greater capabilities and capacity, as necessary, to protect U.S. air, land and sea borders in the Arctic region;

- Increase Arctic maritime domain awareness in order to protect maritime commerce, critical infrastructure, and key resources;

- Preserve the global mobility of U.S. military and civilian vessels and aircraft throughout the Arctic region;

- Project a sovereign U.S. maritime presence in the Arctic in support of essential U.S. interests; and

- Encourage the peaceful resolution of disputes in the Arctic region [1].

Russia is building a new fleet of nuclear powered ice-breakers

Russia is building a new fleet of nuclear powered ice-breakers

(Credit: www.arcticsecurity.org)

The Arctic is centered on a large ocean basin, and as such is covered by the nation’s broader National Ocean Policy. Implemented by Presidential executive order in July 2010, the policy acknowledges changes in the Arctic by directing the government to “address environmental stewardship needs in the Arctic and adjacent coastal areas” as one of its nine policy objectives [2].

Internationally, the U.S. has supported the 15-year old Arctic Council as a forum for Arctic issues. In May 2011, the U.S. was represented for the first time by the Secretary of State and other senior officials at the Arctic Council’s ministerial meeting in Greenland. The most tangible output of the meeting was an international Search and Rescue Agreement for the Arctic [3].

Supplementing a similar framework of national responsibilities around the world, the SAR agreement assigns geographic responsibilities for the Arctic among the nations in the region. It was followed two weeks later by a joint statement by the Presidents of the U.S. and the Russian Federation, announcing deepened cooperation in the Bering Strait region [4].

While both agreements provide commendable frameworks for cooperation, neither addresses capabilities for actually conducting search and rescue operations in the vastness of the Arctic or accomplishing any specific objectives in the Bering Strait.

The SAR agreement and the Bering Strait statement thus symbolize the much larger dilemma of current U.S. engagement in the Arctic *.

Lots of words are inscribed on paper, but the U.S. has, unlike many other nations, failed to make any tangible investments in its Arctic future. We have policy galore, but the capabilities are missing.

The Capability Gap

Does this lack of Arctic capability make any difference?

Only if the directions to protect our borders, commerce, resources and critical infrastructure, preserve global mobility, project a sovereign presence, and encourage dispute resolution, as stated in NSPD-66/HSPD-25, are important.

At an Arctic symposium in June 2011, the head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration stated that her agency lacked the ability to provide adequate weather and ice forecasting and proper charting information for current needs in the Arctic.

Her remarks were followed by a statement from the Commandant of the Coast Guard, who indicated that he could not respond adequately to a cruise ship in distress or an oil spill in the American Arctic [5].

The United States cannot for much longer count on low levels of Arctic activity to mask its inaction. As Russia develops the Northern Sea Route for commercial navigation, 15 commercial vessels have registered to haul cargo between Europe and the Far East in 2011 [6].

Northwest Passage transits are increasing every year, including commercial vessels, cruise ships and small “adventure” vessels. All of this traffic must pass close to U.S. shores, through the 50-mile wide Bering Strait. The U.S. Coast Guard estimates that more than 325 ships transited the Bering Strait in 2010, reflecting a rate of increase of 10-20% a year [7].

The Commandant’s warnings about ships in distress and oil spills were not theoretical musings. During the summer of 2010, two tank vessels grounded in the Canadian Arctic, along with a cruise ship that evacuated all of its passengers to a Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker fortuitously in the area.

Where the U.S. is producing policy papers, our international partners and competitors are planning and building real Arctic capability.

- Canada will begin construction of a large polar icebreaker in 2013, has designed ice-strengthened Navy patrol vessels to enforce Arctic sovereignty, and is planning to upgrade its shoreside Arctic infrastructure for defense purposes.

- Russia, as part of a broad initiative to develop its Arctic energy resources, is actively recapitalizing its large but aging Soviet-era icebreaker fleet.

- The European Union has unveiled the technical design of a huge icebreaking research vessel and drillship for Arctic research.

- Even non-Arctic nations are investing in ice-capable vessels: South Korea began operating a research icebreaker for Arctic and Antarctic work in 2010; China is building a second icebreaking vessel due for completion in 2013; and Chile and South Africa have announced plans to build ice-capable vessels for use in their own polar region.

By contrast, the U.S. is in the process of divesting its Arctic capability.

The nation’s multi-mission polar icebreaker fleet is being downsized by a third with the imminent decommissioning of USCGC Polar Sea. This will leave only the Polar Star, 35 years old and half-way through an expensive 2 ½-year refit, and the 11-year old Healy. Unanticipated engine problems in Polar Sea forced the cancellation of two Arctic deployments in late 2010 and early 2011, the result of attempting to keep complex 1960s-era technology in use beyond its reasonable service life.

Credit: http://wilco278.wordpress.com/2008/08/16/so-who-owns-the-arctic/

Credit: http://wilco278.wordpress.com/2008/08/16/so-who-owns-the-arctic/

Again, does this Arctic divestiture really matter?

Certainly we can continue to issue robust policy statements with a straight face, cite objectives we can’t implement or enforce, and sign abstract international agreements.

But we live in a competitive world and it will not likely be fooled for long. We should take heed of statements like this one by Rear Admiral Yin Zhou, a well-known Chinese naval officer, carried by the official China News Service: “The Arctic belongs to all the people around the world as no nation has sovereignty over it….China must play an indispensable role in Arctic exploration as we have one-fifth of the world’s population” [8]. Canada’s Prime Minister Stephen Harper hit the target precisely when, during a visit to the Canadian Forces Arctic base in Resolute, he stated “The first principle of Arctic sovereignty is use it or lose it.” [9]

What needs to be done?

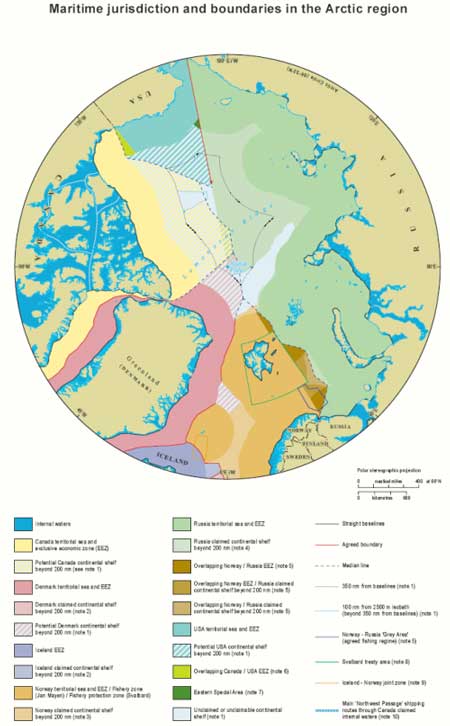

Certainly the United States needs to fill the one gaping hole in our policy foundation, by ratifying the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This will give us a full seat at the international table and allow the U.S. to submit a claim on the extended outer continental shelf, which is particularly at issue in the Arctic Ocean. Certainly we need to improve NOAA’s ice and weather forecasting and chart our Arctic waters to modern standards. And the Defense Department needs to think about how a changing Arctic will fit into future U.S. defense strategy and tactics.

Laudably, this latter issue is being tackled actively. The Chief of Naval Operations in 2009 launched two efforts: an internal “Task Force Climate Change” and a National Research Council study of National Security Implications of Climate Change for U.S. Naval Forces. Both of these initiatives conducted comprehensive reviews of Arctic issues, with the NRC study including the Marine Corps and Coast Guard as well as the Navy.

The task force produced an “Arctic Road Map” for the Navy, and the NRC recommended actions to strengthen the U.S. defense posture in the Arctic. In addition, the Navy convened its 4th Symposium on the Impacts of an Ice-Diminishing Arctic on Naval and Maritime Operations in June 2011, offering a continuing forum for discussion of Arctic defense issues. These actions represent an appropriate application of defense-related “brainpower” to developments in the north.

However, the U.S. capability gap in the Arctic is not primarily a defense shortfall. Despite some occasional breathless prose about high-latitude geopolitical competition and the purported “race” for Arctic resources, there are no nascent international conflicts or national security issues in the region that conceivably approach the level of a defense crisis. Some unsettled matters certainly exist.

But there are no unstable Arctic dictatorships, failed nation states, or armed uprisings that threaten to explode.

In addition, some elements of U.S. “hard power” are already applicable to potential conflicts in the Arctic—submarines, strategic and tactical air assets, even special forces–if events were to reach that level.

Instead, most of the increasing human activity in the Arctic Ocean basin points directly toward the missions of the U.S. Coast Guard.

The smallest of the U.S. armed services shoulders the burden for a preponderance of the nation’s maritime affairs, and the issues emerging in today’s Arctic fall squarely upon the Coast Guard.

- Cruise ship aground?

- Oil spill from a ship or exploratory well?

- Unknown foreign vessel traffic close to U.S. shores?

- Potential violations of U.S. laws and regulations?

- Facilitation of critical science work? Defense exercises in a unique environment?

The Coast Guard is responsible for all of these activities and performs them routinely throughout U.S. waters and on the high seas—but very infrequently in the Arctic, where the capabilities are mostly lacking.

Even a cursory review of the Coast Guard’s 11 statutory missions indicates that almost all of them are directly applicable to U.S. interests in the Arctic:

- Search and rescue

- Aids to navigation

- Ice operations (includes vessel assistance and science support)

- Enforcement of laws and treaties

- Living marine resources enforcement

- Marine safety

- Marine environmental response

- Ports, waterways and coastal security

- Defense operations support

Only the missions of counter-drug and migrant interdiction seem unlikely to require attention in the near future.

Perhaps more importantly, the Coast Guard’s ability to mount a credible response when these responsibilities are invoked, even on a seasonal basis, would enhance maritime domain awareness, support North Slope communities, bolster legitimate commerce, and provide an effective sovereign presence in the U.S. Arctic.

The Coast Guard understands its Arctic capability dilemma.

Both the current Commandant, Admiral Robert J. Papp, Jr., and his predecessor, Admiral Thad W. Allen, have been outspoken about the lack of Arctic capability[10]. More formally, the Coast Guard recently published an Arctic Strategic Approach. This document sensibly recognizes that the Arctic is primarily a maritime domain, and that the Coast Guard bears leading responsibilities for advancing U.S. national interests in the region.

Unfortunately, although there are broad statements about the need for developing appropriate capabilities, the Arctic Strategic Approach provides no clues as to what those types of capabilities might actually be, and mentions no plans for acquiring them [11]. Again, the policy sounds good … but it’s hard to find any real substance.

To its credit, the Coast Guard has surged a variety of regular units to the North Slope during each of the last three summers to test operational procedures and effectiveness.

Despite admirable “can-do” enthusiasm, the results of these operations are unsurprising: cutters, boats, aircraft and other equipment have real problems in a harsh environment far from normal logistical support, and the available shoreside infrastructure is inadequate to sustain a even a routine operational presence, much less a contingency event such as an oil spill [12].

A detailed study of the Coast Guard’s mission requirements in both polar regions was begun in January 2009. However, the report from this study effort has not been completed, despite repeated congressional requests. The high latitude study, which may not be released until the fall of 2011 [13], would form a logical basis for proceeding with formulating a capability plan and proceeding with the acquisition of appropriate assets for Arctic use.

Unfortunately, completion of a major study like this one calls for … another study!

The President’s fiscal year 2012 budget requests $5 million for the Department of Homeland Security to conduct an additional study of high latitude requirements.

There are signs that some in the Congress are growing impatient with the nation’s continued status as a “reluctant Arctic power,” propelled only by policy pronouncements and endless studies. In its review of the Administration’s FY 2012 budget request for the Coast Guard, the House of Representatives Appropriations Committee noted that the budget request

…does little to assure the Committee that national interests in the polar regions can be effectively served in coming years. The current Administration has failed to execute the existing National Arctic Policy, as stated in … NSPD-66/HSPD-25 … and appears to be permitting the atrophy of national polar capabilities. As the sustainable service lives of the Coast Guard’s heavy icebreakers rapidly approach their expiration, the need for polar capabilities is intensifying due to the presence of increased vessel traffic and energy exploration resources in the Arctic. Rather than address these issues with a cogent implementation plan, the Administration and Department are delaying the submittal of the Coast Guard’s High Latitude Study and are requesting an additional $5,000,000 for further study of polar needs. As noted previously in this report, the Committee denies the request for the additional $5,000,000 … since the needs are well known and sufficiently documented. The Coast Guard is directed to submit the High Latitude Study and brief the Committee on the resources required to meet polar mission requirements and fulfill the policy directives set forth in NSPD-66/HSPD-25 no later than 45 days after the date of enactment of this Act. [14]

Bridging the Resource Gap

How should the Coast Guard respond to the Congressional appropriators?

The complexities of the Arctic would allow anyone familiar with current issues in the region to quickly produce a lengthy list of action items. Arctic infrastructure requires upgrading, including improved air facilities, logistical support, charting, communications, navigational aids, environmental sensors, and forecasting capabilities, among others. Providing the assets and infrastructure would at first seem to be a huge investment.

But a single, cost-effective action would go far in filling the yawning Arctic capability gap: move forward with replacing the two obsolete U.S. polar icebreakers.

The capabilities inherent in an icebreaker—long endurance, the ability to move throughout ice-covered waters in all weathers, helicopters, boats, cargo space, extra berthing, and command, control and sensor capabilities—provide what is in effect a mobile Arctic base.

An on-scene icebreaker can respond to emergencies at sea and ashore, provide regulatory oversight of energy activities, monitor vessels near U.S. waters, facilitate scientific research, oversee and support oil spill responses, and exercise contingency plans with defense, local and international partners.

In short, a patrolling icebreaker would assert a visible and capable U.S. presence. Augmenting the ship with special teams or additional personnel would tailor the response specific situations demand. An on-scene icebreaker would address every one of the NSPD-66/HSPD-25 implementation policies.

It’s not as if this is a new or startling insight. Studies of icebreakers and polar issues have consistently recognized the need for recapitalizing U.S. icebreaker assets, including a comprehensive National Research Council study issued in 2007, which concluded, “…the nation continues to require a polar icebreaking fleet that includes a minimum of three multi-mission ships…” [15].

Credit: www.barentsobserver.com

Credit: www.barentsobserver.com

The more recent NRC study of climate change and naval forces concluded “Icebreakers provide important naval force capabilities” and recommended action to ensure the Coast Guard has these icebreaker capabilities [16].

A variety of other studies and reviews have examined the subject; none have come even remotely close to concluding that polar icebreakers are unnecessary or inappropriate to U.S. polar interests. All have indicated that the clock is running out on existing icebreaker capability.

What about the other end of the earth? The Antarctic lacks newsworthy Russian flag plantings and competition for energy resources. The remarkably stable Antarctic Treaty regime has set aside territorial claims and forestalled political conflict for more than 50 years, precipitated in large measure by U.S. leadership.

The effectiveness of this leadership is based—no surprise here—on the most active national presence on and around the Antarctic continent, enabled by the ability to conduct extensive air operations and support large numbers of scientific personnel. Icebreaking assistance for supply ships is the logistical key to the bulk of the U.S. Antarctic Program.

As is the case in the Arctic, U.S. Antarctic activities are also feeling the effects of “capabilities reluctance.” Coast Guard icebreakers supported the annual resupply effort in Antarctica every year since 1955. In 2005, however, the National Science Foundation elected to lease first a Russian and then a Swedish icebreaker for the job. This option has proven expedient, at least until the Swedish government indicated earlier this spring that recent harsh winters in the Baltic may require the Swedish ship to remain in home waters for the 2011-2012 season. Having neither Polar Star nor Polar Sea operationally ready for this unanticipated task, logistics for virtually the entire U.S. Antarctic Program are currently uncertain.

An End to Arctic Reluctance?

It is clearly time for the U.S. Arctic power to shed its reluctance and put some substance behind the substantial policy pronouncements. Despite the fact that government spending is currently under tremendous pressure, national interests in this rapidly transforming part of the world require investment, rather than continued disinvestment. Icebreakers are expensive ships, requiring strengthened hulls, powerful propulsion systems, endurance, and the ability to operate effectively in extreme environments.

But a pair of replacement icebreakers, replacing the unsupportable and expensive to operate Polar Star and Polar Sea would catapult the U.S. from a paper Arctic power to one with real capabilities, across the spectrum of national power. New, efficient, environmentally-compliant icebreakers would give the U.S. positive control of its Arctic Ocean and Bering Sea frontier—as well as the ability to sustain its Antarctic presence credibly.

Polar icebreakers represent a “Swiss Army knife” approach. In this case, a single versatile tool would be far cheaper than an elaborate tool chest of specialized but seldom-required implements.

The Coast Guard would be foolish to attempt to duplicate its lower-48 infrastructure of aircraft and boat stations, shore support facilities for larger vessels and special teams, and marine safety offices. Not only would these facilities be horrifically expensive to build on the shallow and eroding North Slope coastline underlain with slowly melting permafrost, but the seasonal nature of operational requirements won’t foreseeably require year-round, bricks-and-mortar facilities. Flexible capabilities that can act in the waterspace and move to the scene of the action are far better suited to the region.

As the House Appropriations Committee has recognized, ahead of the Executive Branch, it is time to move forward.

For Dr. James Carafano’s comment see

http://blog.heritage.org/2011/07/09/united-states-is-poorly-prepared-to-defend-interests-in-arctic/

——–

References

* See the Arctic Mission from SLD

Notes

[1] National Security Presidential Directive/NSPD-66 Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD-25, Arctic Region Policy, January 9, 2009.

[2] National Ocean Council, National Priority Objectives, Executive Order “Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes,” July 19, 2010.

[3] “Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic,” May 12, 2011, http://www.arcticcouncil.org.

[4] “Joint Statement of the President of the United States of America and the President of the Russian Federation on Cooperation in the Bering Srait Region,” Office of the White House Press Secretary, May 26, 2011.

[5] “NOAA: U.S. unprepared for changes in Arctic ice,” Renee Schoof, McClatchey Newspapers, June 20, 2011, www.miamiherald.com/2011/06/20/2276032/noaa-us-unprepared-for-changes.html

[6] “Arctic should be accessible to all,” Lyudmila Morozova, Voice of Russia, June 28, 2011, http://english.ruvr.ru/2011/06/28/52511043.html.

[7] “Arctic Maritime Transportation,” a briefing by RADM Christopher C. Colvin, USCG, February 25, 2011, www.institutenorth.org/assets/…/APF_Rear_Admiral_Christopher_Colvin.pdf

[8] “China’s Arctic Play,” by Gordon G. Chang, The Diplomat, March 9, 2010.

[9] “Canada to strengthen Arctic claim,” BBC News, August 10, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6941426.stm.

[10] Recent examples include “Coast Guard Commandant Makes Plea for More Arctic Resources,” Seapower, May 2011; “Coast Guard needs greater Arctic presence, admiral advises,” Gene Johnson, Associated Press, Anchorage Daily News, May 31, 2011.

[11] U.S. Coast Guard Strategic Approach, Commandant Instruction 16003.1, April 26, 2011.

[12] “With ship traffic rising, Coast Guard considers building an Arctic presence,” Alex DeMarban, The Arctic Sounder, May 21, 2011, www.thearcticsounder.com/article/1122with_ship_traffic_rising_coast_guard

[13] “House panel rips Coast Guard for red tape,” Christopher P. Cavas, Nay Times, June 27, 2011.

[14] 112th Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Appropriations Report 112-91, in explanation of the accompanying bill making appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2012.

[15] Polar Icebreakers in a Changing World: An Assessment of U.S. Needs, National Research Council, 2007.

[16] National Security Implications of Climate Change for U.S. Naval Forces, National Research Council, 2011.