2013-12-03 by Robbin Laird

The challenge of reshaping Pacific defense to deal with the various strategic challenges of the 21st century – the Arctic opening, SLOC and maritime trade conveyer belt security, North Korea and the dynamics of the second nuclear age, and the reaching out into the Pacific by the PRC – is about augmenting Pacific defense and an ability of the U.S. and its allies to operate collaboratively over the geographic expanse of the Pacific.

What we have called the strategic quadrangle in the Pacific is a central area where the U.S. and several core allies are reaching out to shape collaborative defense capabilities to ensure defense in depth.

This area is central to the operation of forces from Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, Singapore and the United States, to mention the most important allies.

Freedom to operate in the quadrangle is a baseline requirement for allies to shape collaborative capabilities and policies. Effectiveness can only emerge from exercising evolving forces and shaping convergent concepts of operations.

In our book on the shaping of a 21st century strategy, we highlight Pacific operational geography as a key element for forging such a strategy.

In effect, U.S. forces operate in two different quadrants—one can be conceptualized as a strategic triangle and the other as a strategic quadrangle.

The first quadrant—the strategic triangle—involves the operation of American forces from Hawaii and the crucial island of Guam with the defense of Japan. U.S. forces based in Japan are part of a triangle of bases, which provide for forward presence and ability to project power deeper into the Pacific.

The second quadrant—the strategic quadrangle—is a key area into which such power needs to be projected. The Korean peninsula is a key part of this quadrangle, and the festering threat from North Korea reaches out significantly farther than the peninsula itself.

The continent of Australia anchors the western Pacific and provides a key ally for the United States in shaping ways to deal with various threats in the Pacific, including the PRC reach deeper into the Pacific with PRC forces. Singapore is a key element of the quadrangle and provides a key ally for the United States and others in the region.

A central pressure in the region is that each of the key allies in the region works more effectively with the United States than they do with each other.

This is why the United States is a key lynchpin in providing cross linkages and cross capabilities within the region. But it is clear that over time a thickening of these regional linkages will be essential to an effective 21st-century Pacific strategy.

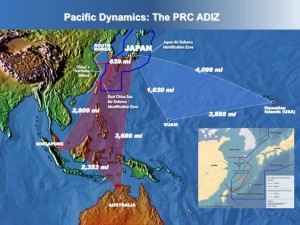

The distances in these regions are immense.

For the strategic triangle, the distance from Hawaii to Japan are nearly 4,100 miles. The distance from Hawaii to Guam—the key U.S. base in the Western Pacific—is nearly 4,000 miles. And the ability of Guam to work with Japan is limited by the nearly 2,000-mile distance between them as well.

For the strategic quadrangle, the distances are equally daunting. It is nearly 4,000 miles from Japan to Australia. It is nearly 2,500 miles from Singapore to Australia and nearly 3,000 miles from Singapore to South Korea.

Clearly, air and naval forces face significant challenges in providing presence and operational effectiveness over such distances.

This is why a key element of shaping an effective U.S. strategy in the Pacific will rest on much greater ability for the allies to work together and much greater capability for U.S. forces to work effectively with those allied forces.

(From Chapter I: The Pacific Landscape of Operations).

The allies are looking to the operational quadrangle as a key area within which to project force outwards and to find ways to expand both the effectiveness and survivability of a flexible force.

Air platforms have the distinct advantage of flexibility in operations, and with an ability to operate from various land and sea bases can operate from different trajectories of operation as well.

In addition to committing resources to buying a new generation of combat aircraft, core allies see air tanking as a key infrastructural element to allow them to operate more effectively into the quadrangle.

The United States has pioneered air tanking in the Pacific and remains the key player drawing upon its air tanker infrastructure to operate over the vast distances in the region.

The United States has used KC-130J tankers in innovative ways working with the Osprey to make the Osprey a longer reach asset able to operate over the chessboard of the Pacific islands, landing zones and seabases. An Osprey tanker is being added to the mix which will only make the reach and range of various USMC and USN assets much greater.

The USAF will be adding new tankers to the mix in the decade ahead, and is looking at ways to shape tanker capabilities which might effectively refuel remotely piloted vehicles in the future.

The allies are joining in to the effort, precisely to provide greater reach and range for their air assets as well as significantly greater operational flexibility.

Two of those allies have already committed to buying the A330MRTT and in the case of Australia already has five planes in its inventory.

In an earlier piece, the role of the A330MRTT tanker in Australian thinking was highlighted by comments made by Commodore Gary Martin, commander Air Lift Group in late 2012:

“This aircraft can take six fighters from Australia to the mainland United States happily. Its loiter time and offload is almost TWICE that of a US Air Force KC-10A Extender.”

According to Commodore Martin: “The KC-30A has participated in exercises Pitch Black, Arnhem Thunder, Kakadu and High Sierra in the last 4 ½ months, almost and exercise a month, and in September we flew 71 sorties with two of the three aircraft delivered, over half of which were air to air refueling missions.”

According to Commodore Martin: “It is such a big aeroplane and the feedback is that it’s the easiest aeroplane they’ever connected to. Out of the 50 per cent of the 71 sorties we fles last month, the AAR missions, we didn’t have a single aircraft turn away from us.”

India is also joining the A330MRTT family and given the reach which the Indian Navy and Air Force is considering with new facilities and challenges in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, it is not surprising that they want a long range tanker solution.

I wrote earlier about the Indian decision:

Instead of going for a modernized version of the IL-78, the Indians have announced their intention to go with the A330MRTT.

Such a decision is based on several considerations.

First, the fuel payload is greater on the A330MRTT. In terms of physical specs, the A330MRTT can carry 30% more fuel than the IL-78. And the greater fuel efficiency of the engines aboard the Airbus tanker will allow for de facto even greater capability to deliver more fuel to the Indian deployed air fleet.

Second, the A330MRTT can carry more passengers than the IL-78. The Airbus tanker can carry more than 300 passengers as opposed to around 250 aboard the IL-78.

Third, the A330MRTT has significantly expanded MRO options than the IL-78. The IL-78 is a specialized aircraft and requires contractor specific support. The advantage of the A300MRTT is that it is an A330.

Indians can have a wide variety of MRO opportunities in the region for support for the aircraft. The Indians can craft a cost effective, combat effective MRO solution set.

Fourth, the Indians are buying a new tanker to deal with the current fleet, but to prepare for their overall modernization. The P-8 is entering the inventory and is boom-ready and having a boom capable tanker makes a great deal of sense to expand Indian options over the next 50 years.

Currently, the Indians fly with only a hose-drogue refueling system. This is clearly limiting when it comes to combat fleet modernization.

In other words, the A330MRTT option will allow the Indians to deal with current needs but to lay a foundation for effective support of their modernization options.

Both South Korea and Singapore are about to enter the tanking world as well.

The South Koreans clearly see the need to operate beyond the narrow range of the Korean peninsula, and Singapore sees its maritime interests best served by adding a new tanker capability. But the impact will be to bring South Korean and Singaporean assets deeper out into the strategic quadrangle.

After the spirited debate about the future of combat aircraft – F-15s versus F-35s, the South Koreans have settled on shaping a role in the F-35 pacific fleet as the preferred option. And along with this, South Korean officials see the advantage of moving the legacy and new aircraft further out in operational terms to have the kind of operational flexibility, which 21st century strategic challenges provide.

As one source put it:

Seoul has long sought to fly aerial tankers to help extend the operational range of its fighter jets as part of efforts to respond to potential territorial disputes with neighboring countries.

“Now, our fighter fleet of F-15Ks and KF-16s are able to fly missions near the eastern most islets of Dokdo as a legacy of its imperial past, only for 30 minutes,” an Air Force officer said. “With mid-air refueling, however, the operational range and flight hours will be extended, along with an increase in strike distance.”

For Singapore, tankers are already in the fleet, but they are looking to modernize that fleet.

According to a source the Singaporeans have placed:

Aerial refueling tankers at the top of the list because the air force needs to replace its four Boeing KC-135Rs. An important requirement is that the new tankers be able to assist the air force’s Boeing F-15SGs flying between Singapore and its overseas detachment at Mountain Home AFB, Idaho…..

However, industry executives familiar with the situation say the front-runner in this competition is the Airbus Military A330 Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT)….

Singapore Technologies Aerospace, the Singapore government-linked company that maintains many of the air force’s aircraft, is also familiar with the A330, because it does the heavy maintenance work on Singapore Airlines’ (SIA) fleet of leased A330 passenger aircraft.

This means that all of the major allies operating in the strategic quadrangle will be adding tankers or modernizing tankers in the decade ahead.

This decade is laying down the foundation for innovation in the next.

The Japanese are buying the new Boeing tanker; Australia already has deployed the new Airbus tanker, and India is to follow suit.

South Korea and Singapore have yet to decide, but a case can be made for them to add A330 tankers to those of their allies and to shape a very interesting infrastructure to operate in the strategic quadrangle.

The A330 MRTT tanker as a fleet provides the possibility for a network of flying air support systems engaged for a long time in an operational setting.

Much depends on how these assets become configured.

With the fuel carried in the wings, the large deck of the A330 can be used to host a variety of air support capabilities: routers, sensors, communication nodes, etc.

Such a configuration along with the fuel re-supply capabilities of the A330 tanker makes this a flying air operational support asset.

If the model selected is similar to the model downselected initially by the USAF, it is refuelable in flight.

With the space available in the aircraft – again because of the fact that the fuel for refueling is carried in the wings – a crew rest area can be provided.

This means that the air tankers can stay aloft for a significant period of time as the refuelers are themselves refueled.

This in turn means that the refueling aircraft as a fleet can have a strategic impact.

Once the planes are airborne and they have access to refuelers for their own operational autonomy, the fleet can tank a variety of national or coalition partners operating from dispersed or diverse airfields.

And the discretion possible airborne can allow nations to tank a variety of coalition partners, some of whom might not be favorite candidates if seen on the ground.

The Indian case is instructive.

Earlier I laid out how the new tanker infrastructure could play into the requirements for extended Indian defense and of course support them operating in the strategic quadrangle as well.

Dependent upon how the Indians address the use of the platform, the A330MRTT could become a key element not only enhancing operational capability but innovation as well.

The strategic challenge facing India was well articulated by Robert Kaplan in his book, Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power.

According to Kaplan, China is expanding vertically and India horizontally on the global stage.

Competition between India and China, caused by their spreading and overlapping layers of commercial and political influence, will play out less on land than in a naval realm. Zhao Nanqi, when he was the director of the general staff logistics department in the Chinese navy, proclaimed: “We can no longer accept the Indian Ocean as an ocean only of the Indians.”

This attitude applies particularly to the Bay of Bengal, where both nations will have considerable maritime presences, owing to the closeness of Burma as well as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, possessed by India near the entrance of the Strait of Malacca.

Conversely, India’s and China’s mutual dependence on the same sea lanes could also lead to an alliance between them that, in some circumstances, might be implicitly hostile to the United States. In other words, the Indian Ocean will be where global power dynamics will be revealed. Together with the contiguous Near East and Central Asia, it constitutes the new Great Game in geopolitics.

But as India and China become more integrally connected with both Southeast Asia and the Middle East through trade, energy, and security agreements, the map of Asia is reemerging as a single organic unit, just as it was during earlier epochs in history—manifested now by an Indian Ocean map.

Kaplan, Robert D. (2010-10-19). Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (Kindle Locations 282-292, selections). Random House, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

The A330MRTT is an ideal tool to help India integrate its various maritime and air assets necessary to cover a wide territory for horizontal operations…..

The A330MRTT as a global tanker has been designed from the ground up to provide for the tanking of virtually every fighter, bomber or support aircraft flying today. And as the unmanned fleets or remotely piloted aircraft get added to the mix, the A330MRTT will be ready to refuel these as well.

In other words, the tanker is well designed for today and has growthability to deal with the next 50 years of the evolution of military aviation in mind. It is not narrowly constructed as a simple upgrade from the past but can grow with the combat and support fleets.

And the reach of the Indian navy will grow over time and with it deployed Naval aviation assets whose reach will be defined by the ability to be tanked and supported…..

In short, as India shapes a “horizontal” defense and security strategy, the Indians will add new air and naval platforms.

But equally important will be the infrastructure to support such deployed assets.

And no asset is more important than shaping an effective airborne support structure for the Indian forces being built in the 21st century.

Looking beyond India and Australia, if Singapore and South Korea become part of the A330MRTT fleet, a new Pacific defense infrastructure would be crafted airborne so to speak.

The Pacific allies can gain strategic depth airborne. By having similar and shared assets and training, they can support one another’s fighters and other air assets and provide the capability for a nation’s planes to operate off of airfields or seabases which are not their own.

This provides a significant enhancement of strategic depth of the sort required to operate collaboratively within the strategic quadrangle.

And with the U.S. facing tanker shortages because of the age of its fleet, and the slow pace of tanker modernization, Pacific allies can make a significant contribution to U.S. operations within the strategic quadrangle as well.

Editor’s Note: Below is the description of the A330MRTT in service for the Royal Australian Air Force from the RAAF website:

The Royal Australian Air Force operates five KC-30A Multi Role Tanker Transports (MRTT), which are a heavily modified Airbus A330 airliner used for air-to-air refuelling and strategic transport. The KC-30A is able to refuel Air Force’s F/A-18A/B Hornet and F/A-18F Super Hornets, as well as the E-7A Wedgetail Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft, C-17A Globemaster, and other KC-30As.

It will be compatible with refuelling the P-8A Poseidon surveillance aircraft and F-35A Lightning II when these aircraft enter Air Force service.

The aircraft are fitted with two forms of air-to-air refuelling systems – an Aerial Refuelling Boom System (ARBS) mounted on the tail of the aircraft, which comprises a ‘fly-by-wire’ boom refuel system; and a pair of all-electric refuelling pods underneath each wing, which unreel a hose-and-drogue to refuel probe-equipped aircraft. These systems are controlled by an Air Refuelling Operator in the cockpit, who can view refuelling on 2D and 3D screens.

TThe KC-30A has a fuel capacity of more than 100 tonnes, and can remain 1800km from its home base with 50 tonnes of fuel available to offload for up to four hours. In its transport role, the KC-30A will be capable of carrying 270 passengers, comes with under-floor cargo compartments and will be able to accommodate 34,000kgs of military and civilian cargo pallets and containers.

Advanced mission systems will also be fitted. They include the Link 16 real-time data-link, military communications and navigation suites, and an electronic warfare self-protection system for protection against threats from surface-to-air missiles.

The KC-30As are operated by No 33 Squadron located at RAAF Base Amberley.