2013-12-02 By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

The PRC has recently declared an Air Defense Identification Zone, which covers not just its territory but those of Japan as well.

A key consideration as well is the NATURE of the rules, which the PRC is seeking to enforce in their self-declared ADIZ.

The PRC is seeking to enforce rules that are different from standard rules for an air identification zone. The Chinese authorities require reports from all aircraft that plan to pass through the zone, regardless of destination.

In contrast, Japan and the United States have their own air defense zones but only require aircraft to file flight plans and identify themselves if those planes intend to pass through national airspace. And in Japan, the Air Self Defense Force receives information on flight plans of incoming civil aircraft from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism, but does not seek reports directly.

As Bonnie Glaser put it:

China’s Aircraft Identification Rules make no distinction between aircraft flying parallel with China’s coastline through the ADIZ and those flying toward China’s territorial airspace.

Secretary of State Kerry highlighted this issue in his statement, saying that the US “does not apply its ADIZ procedures to foreign aircraft not intending to enter US national airspace,” implying that the US would not recognize China’s claimed right to take action against aircraft that are not intending to enter its national airspace.

The PRC Air Defense Identification Zone may seem an anomaly or an irrational act challenging multiple players in the Pacific.

But what it is in reality is the opening gambit in trying to impede and defeat the formation of a 21st century Pacific defense and security strategy by the U.S. and its allies.

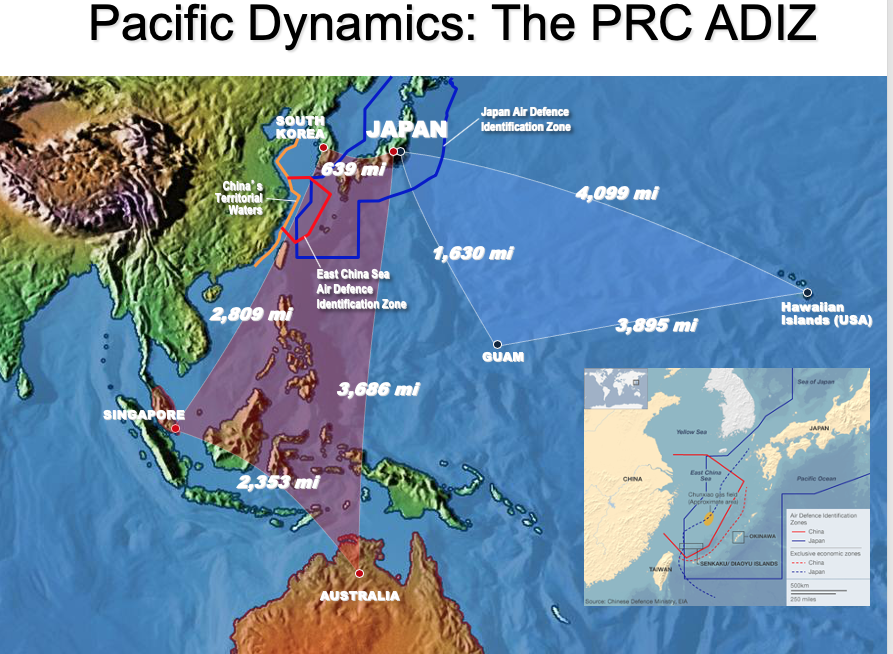

What we have called the strategic quadrangle in the Pacific is a central area where the U.S. and several core allies are reaching out to shape collaborative defense capabilities to ensure defense in depth.

This area is central to the operation of forces from Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, Singapore and the United States, to mention the most important allies.

These allies are adding new air and maritime assets and are working to expand the reach and range of those assets through various new capabilities, such as air tanking and the shaping of electronic surveillance and defense assets.

Freedom to operate in the quadrangle is a baseline requirement for allies to shape collaborative capabilities and policies. Effectiveness can only emerge from exercising evolving forces and shaping convergent concepts of operations.

This requires time; this requires practice; and this requires introducing new systems such as A330 tankers and F-35s, P-8s, or Wedgetails into the operational area.

In our book on the shaping of a 21st century strategy, we highlight Pacific operational geography as a key element for forging such a strategy.

In effect, U.S. forces operate in two different quadrants—one can be conceptualized as a strategic triangle and the other as a strategic quadrangle.

The first quadrant—the strategic triangle—involves the operation of American forces from Hawaii and the crucial island of Guam with the defense of Japan. U.S. forces based in Japan are part of a triangle of bases, which provide for forward presence and ability to project power deeper into the Pacific.

The second quadrant—the strategic quadrangle—is a key area into which such power needs to be projected. The Korean peninsula is a key part of this quadrangle, and the festering threat from North Korea reaches out significantly farther than the peninsula itself.

The continent of Australia anchors the western Pacific and provides a key ally for the United States in shaping ways to deal with various threats in the Pacific, including the PRC reach deeper into the Pacific with PRC forces. Singapore is a key element of the quadrangle and provides a key ally for the United States and others in the region.

A central pressure in the region is that each of the key allies in the region works more effectively with the United States than they do with each other.

This is why the United States is a key lynchpin in providing cross linkages and cross capabilities within the region. But it is clear that over time a thickening of these regional linkages will be essential to an effective 21st-century Pacific strategy.

The distances in these regions are immense.

For the strategic triangle, the distance from Hawaii to Japan are nearly 4,100 miles. The distance from Hawaii to Guam—the key U.S. base in the Western Pacific—is nearly 4,000 miles. And the ability of Guam to work with Japan is limited by the nearly 2,000-mile distance between them as well.

For the strategic quadrangle, the distances are equally daunting. It is nearly 4,000 miles from Japan to Australia. It is nearly 2,500 miles from Singapore to Australia and nearly 3,000 miles from Singapore to South Korea.

Clearly, air and naval forces face significant challenges in providing presence and operational effectiveness over such distances.

This is why a key element of shaping an effective U.S. strategy in the Pacific will rest on much greater ability for the allies to work together and much greater capability for U.S. forces to work effectively with those allied forces.

(From Chapter I: The Pacific Landscape of Operations).

In an interview we did earlier this year with Lt. General Robling who is MARFORCPAC, the General highlighted the significance of the geographical challenge to the kind of persistent presence the US is seeking in working with allies:

To get from Hawaii into the strategic triangle or quadrangle takes significant time. Between Hawaii and Okinawa is about 5 steaming days. It is longer to get to Australia and Guam and then back up to Okinawa and Tokyo within the Quadrangle.

Strategic aircraft lift – C-17s – cuts that time down significantly…hours vice days. However, they are expensive to use, take several sorties to move the same amount of equipment you could move on shipping and are not always available.

Our strategic partners and allies are spread out over a significant geographical area.

They want to train with us, but not always bilaterally, they sometimes want us to work with them and some or several of their partner countries.

That means we must take the training to them.

Enter the PRC and its attempt to declare an Air Defense Identification Zone or ADIZ.

This is clearly a significant gambit to take a bit out of the strategic quadrangle and to foment discord among allies.

According to a Japan Times article about the ADIZ:

The (Japanese) government branded as “very dangerous” China’s announcement Saturday that it has set up an East China Sea air defense identification zone that includes the Japan-held Senkaku Islands.

The Chinese Defence Ministry said the zone was created to “guard against potential air threats,” but the move will only inflame a bitter sovereignty row over the islets, which China claims as Diaoyu.

Later Saturday, China scrambled air force jets, including fighter planes, to patrol the new zone…..

(The new zone) covers a wide area of the East China Sea between South Korea and Taiwan, and includes the Senkaku islets…..

Along with the new zone, the Chinese ministry released a set of aircraft identification rules that it says must be followed by all aircraft entering the area, under penalty of intervention by China’s military.

Aircraft are now expected to provide their flight path, clearly mark their nationality and maintain two-way radio communication in order to “respond in a timely and accurate manner to identification inquiries” from Chinese authorities….

This last point is an important one: for the PRC is asserting its right to verify the operations of all aircraft, whether commercial or military and whether intending to enter PRC territory or not.

This might seem a irrational act of a power hungry power but seem from the perspective of the strategic geography of the Pacific it is not.

The PRC is putting down its marker onto the quadrangle and if not dealt with will undoubtedly expand its definitions of air and maritime defense outward.

We have placed the ADIZ down upon the strategic geography we have identified and a key reality quickly emerges. Just by chance the zone covers reinforcements to Taiwan.

This is clearly a backhanded attempt to promote the PRC’s view of the nature of Taiwan and the South China Sea in their defense calculus.

There have been hints as well that the PRC is looking to do something similar with Vietnam in mind.

China is about to establish a second air defense identification zone over the South China Sea, Qin Gang, spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry, said on Nov. 25, according to the Moscow-based Voice of Russia.

Qin said the air defense identification zone over the East China Sea announced by Beijing on Nov. 23 was a buffer zone to defend the territorial integrity of China and said a second air defense identification zone which may cover the disputed South China Sea will be established in due course.

The Vietnamese case could prove interesting, not only in terms of expanding the Pacific defense equation dealing with the PRC seeking to expand its area of control out into the Pacific.

We have made the case in the book that focus of a 21st century US strategy is Pacific defense, not simply a U.S. military strategy in the Pacific.

The PRC focus on Vietnam is a good case in point because it will lead immediately to PRC-Indian “discussions.”

The recent Indian and Vietnamese summit focused among other things upon the further development of Vietnamese resources and augmenting its defense capabilities.

According to a Thanh Nien story drawing upon a Times of India story:

India’s navy is training over 500 Vietnamese submariners as part of the countries’ resolution to expand bilateral military ties, the Times of India reported last week.

During talks between Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and visiting Communist Party general secretary Nguyen Phu Trong last Wednesday, it was decided that India would issue Vietnam a US$100 million line of credit for the purposes of enabling the latter to acquire four naval patrol vessels from the former, the report said.

The ongoing training of Vietnamese sailors in “comprehensive underwater combat operations” at the Indian Navy’s submarine training center, INS Satavahana in Visakhapatnam, is a major bilateral initiative of the nations’ emerging strategic partnership.

Over 500 Vietnamese sailors will be trained in batches at the center, which is equipped with state of the art technology, by the Indian Navy, according to the report.

In December 2009, Vietnam signed a $2 billion deal to buy six submarines from Russia, which is due to deliver them all by 2016.

The Indian Navy’s extensive experience in operating Russian Kilo-class submarines, which dates back to the mid-1980s, will be invaluable to Vietnam as its navy learns how to handle their new underwater vessels, according to the Times of India.

In the past, India has supplied spare parts for Russian Petya class warships and Vietnamese OSA-II class missile boats.

“India will continue to assist Vietnam to modernize and train its defense and security forces, including via the $100 million line of credit for defense purchases,” said PM Singh.

And The Japan Times added additional information, which highlighted the importance of the recent Vietnamese-Indian summit:

India and Vietnam made serious efforts to upgrade their bilateral relations earlier this month during the visit to New Delhi by Vietnamese Communist Party Secretary General Nguyen Phu Trong.

Eight pacts were inked, including ones on energy cooperation and protection of information, which are strategically significant areas that will influence the trajectory of this bilateral relationship.

Vietnam has offered seven oil blocks to India in South China Sea, including three on an exclusive basis where Hanoi is hoping for production-sharing agreements with India’s state-owned oil company ONGC Videsh Ltd. (OVL).

In a significant move, India has also decided to offer a $100 million credit line to Vietnam to purchase military equipment. Usually a privilege reserved for its immediate neighbors, this is the first time that New Delhi has made such an offer to a more distant nation.

Delhi and Hanoi have been working toward building a robust partnership for the past few years.

It is instructive that India entered the fraught region of the South China Sea via Vietnam.

New Delhi signed an agreement with Vietnam in October 2011 to expand and promote oil exploration in the South China Sea and then reconfirmed its decision to carry on despite the Chinese challenge to the legality of an Indian presence.

Beijing told New Delhi that its permission was needed for India’s state-owned oil and gas firm to explore for energy there. But Vietnam quickly cited the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to claim its sovereign rights over the two blocks in question.

Hanoi has been publicly sparring with Beijing over the South China Sea for the last few years, so such a response was expected.

What was new, however, was New Delhi’s newfound aggression in taking on China. It immediately decided to support Hanoi’s claims.

By accepting the Vietnamese invitation to explore oil and gas in Blocks 127 and 128, OVL not only expressed New Delhi’s desire to deepen its friendship with Vietnam, but also ignored China’s warning to stay away.

A clear message from our recent discussion with General Hawk Carlisle, the AFPAC commander, was that enhancing allied cooperation among themselves as well as working with the U.S. was a core American objective in shaping Pacific defense.

In the interview, he noted that the U.S.-Japanese relationship is undergoing a fundamental transformation. The Japanese are clearly rethinking their defense posture and he argued that the U.S. was working much more deeply and comprehensively with the Japanese defense forces than even two years ago. For example, “We have moved our air defense headquarters to Yokota Air Base and we are doing much closer coordination on air and missile defense with the Japanese to deal with a wider spectrum of regional threats.”

The Air Force is stepping up its collaborative efforts and capabilities with key regional air forces, including with Australia, Singapore, South Korea and Japan. And Carlisle emphasized that the service is pushing to enhance cross-collaborative capabilities among those allies as well.

While trying to get the allies to work more closely with each other, the Pacific commander also underscored that the US Air Force is adopting allied innovations.

“Singapore is doing very innovative things with their F-15s, notably in evolving the capabilities of the aircraft to contribute to maritime defense and security. We are looking very carefully at their innovations and can leverage their approach and thinking as well,” he said. “This will certainly grow as we introduce the fleet of F-35s in the Pacific where cross national collaboration is built in.”

Forging paths towards cross-domain synergy among joint and coalition forces is a key effort underway.

There is a tendency in Washington to believe that PRC actions are really just directed against the United States.

This misses a fundamental point: Pacific allies and the United States are seeking to shape an effective 21st century defense strategy, in which the US is clearly important but not the only player.

The PRC understands this and is working towards Ben Franklin moments for the US and its allies.

We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.

The PRC leadership hopes that discord between the US and its allies and among the Pacific allies themselves will lead them to chose hanging separately.

It is a gamble but apparently one worth taking for the PRC leadership.

For our briefing to the Air Force Association Pacific Forum in late November 2013 see the following: