2015-08-04 This Spring, the Marine Corps hosted an amphibious conference in Hawaii which provided a first of its kind look at the evolution of amphibious capabilities in the region. 23 nations from the region joined the Marines and Navy in looking at the amphibious dynamic and discussing ways ahead within the region.

In part this is happening because of the demonstrated utility for the afloat force to provide for humanitarian assistance of simply connectivity and support in a crisis in addition to more robust approaches to military operations.

In a discussion with Brigadier General Mahoney, Deputy MARFORPAC, the emergence of what the Marines call “amphibiosity” within the region was a key point of discussion.

There are clear differences in the region between those who focus on an older concept of amphibious forces as transit or transportation assets and those who see a more robust role for those forces within an overall integrated force structure.

A challenge is simply the ambiguity of what amphibious means in the wake of the Osprey revolution and the coming of the F-35B.

As one Marine put aboard the USS WASP:

“No one in the world has ever sent an airplane off of an amphibious ship with this level of situational awareness and fusion between aircraft to aircraft and aircraft to ship.

The fusion of the data aboard the airplanes and your ability to see what other planes are seeing a number of miles away from you, as well as what the ship is seeing, and then to be able to communicate with them without using the radio is a tactical and strategic advantage that can not really be over stated.”

And with the Osprey, now the amphibious ready group operates over a vastly increased area and is able to prosecute a wide variety of tasks over that operational area.

Part of the problem is that this innovation has left the classic discussion of amphibious operations behind so much so that when the USS America has been delivered to the fleet, that the absence of a well deck to launch amphibious vehicles close to shore was seen as an aberration within the amphibious construct.

Rather, the amphibious equation is now about lashing up Military Sealift Command assets (which is about a third of the assets in PACFLEET) with grey hulls to deliver a new approach to amphibious operations.

But at the same time, the C2 shortfalls created by the new capabilities.

Ships like the USS Arlington, which were to operate in close proximity to other ships in amphibious operations, now are operating much more independently and the result is a significant C2 gap.

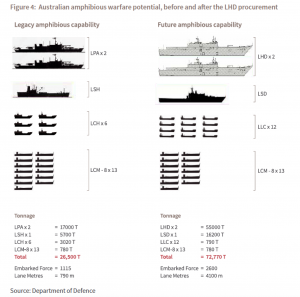

The Australians are adding two new LHD ships precisely as the USN-USMC team revolutionizes amphibious operations and redefines “amphibiosity.”

The challenge for the Australian forces is discussed in a recent publication of the Australian Strategy Policy Institute and provides a good reach to look at the evolving Australian opportunity and challenge.

Beyond 2017: The Australian Defence Force and amphibious warfare

https://www.aspi.org.au/publications/beyond-2017-the-australian-defence-force-and-amphibious-warfare

The authors argue the case that the re-crafting of Aussie amphibious capabilities makes obvious strategic sense.

Getting into the littoral zone therefore involves amphibious operations. As the importance of the primary operating environment and the Indo-Pacific region grows, so too will the requirement for the ADF to conduct operations in this region that will be highly reliant on sealift and amphibious warfare capabilities.

The significance of amphibious assets is due not only to the rising importance of the littorals, but also to the extreme versatility of those assets. They can operate along the full spectrum of operations, from disaster relief and search and rescue through to the more traditional roles of amphibious assaults, raids, demonstrations and withdrawals.

While to many the word ‘assault’ conjures up operations in the distant past, such as in Normandy or on Iwo Jima, that style of amphibious assault was a bespoke solution to a very specific strategic problem. Such operations are an aberration in the long history of amphibious warfare (page 17).

The authors also highlight the intersection with US developments as a key opportunity as well for the Australian amphibious reset.

Another key element for the development of the Australian amphibious force is the potential for a number of missions in concert with the US and regional partners. The potential to cross-deck US Marines on RAN ships can be easily developed through the presence of Marine Rotational Force Darwin.

In addition, in October 2014, the US Navy’s Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Jonathan Greenert, committed to releasing traditional ‘grey hull’ amphibious ships to create a US Amphibious Ready Group and Marine Expeditionary Unit (ARG-MEU), using the marines in Darwin to operate in Southeast Asia for up to 180 days per year by the end of the decade.

Admiral Greenert reiterated this commitment during his recent visit to Australia, which included a visit to Darwin to inspect infrastructure and port facilities for the amphibious ships. He also said that the US is committed to raising Marine Rotational Force Darwin to full MEU status to operate with an ARG, and indicated that the three US amphibious ships for this task have been identified. Such a move provides enormous opportunities for combined training, coordinated engagement activities and shared security missions in Australia’s northern waters and throughout the South Pacific, Southeast Asia and the eastern Indian Ocean.12

Furthermore, the combination of a US Navy – Marine Corps ARG-MEU with an ADF ARG in the region provides a range of other potential opportunities. In any major crisis in the region, pooling US and Australian amphibious forces along with other assets would allow the formation of a combined US–Australian expeditionary strike group.13 At low threat levels, it would allow an extended presence beyond 180 days, or burden sharing through a rotation of the US ARG-MEU and the ADF’s ARE and ARG to provide a maritime presence for most of the year in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia and the eastern Indian Ocean (page 21).

They focus on the shifts the Australian Army will need to make as well as the importance of working the joint problem as well.

They make a solid case for setting up and amphibious center of excellence as well.

Clearly, C2 and aviation demands are important to resolve as well.

And the C2 side will not be solved within the amphibious fleet itself and is more a joint opportunity as suggested by the RAAF approach to Plan Jericho.

The ability to link across the combat force is not about what organically is ON the amphibious ships but what those ships can connect to in the battlespace.

The connectivity between the Wedgetail and the surface fleet is a key way ahead for managing the amphibious aspect as well.

And buying a Tiger helicopter without working out how to operate it onboard a ship or the same for an F-35B is not how one wants to approach the future of the amphibious ships within an integrated force.

The report really does not discuss the aviation aspect of the amphibious fleet, which for the USN-USMC team has been the most dynamic reshaper of amphibious operations, and this reshaping is really only just under way.

The Australian Army would need to look considerably more like the USMC in terms of ship ready aviation and related systems to get from here to there in 21st century operations.

But given the close relationship this is a very feasible outcome.

Maritime-based helicopter support is part of but not the future of more advanced amphibious operations, and the Plan Jericho opportunity might provide a framework to shape a way ahead for the amphibious fleet in Australia.