2016-03-02 Our colleague Air Vice Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn has focused attention on the energy security shortfall for Australia for some time.

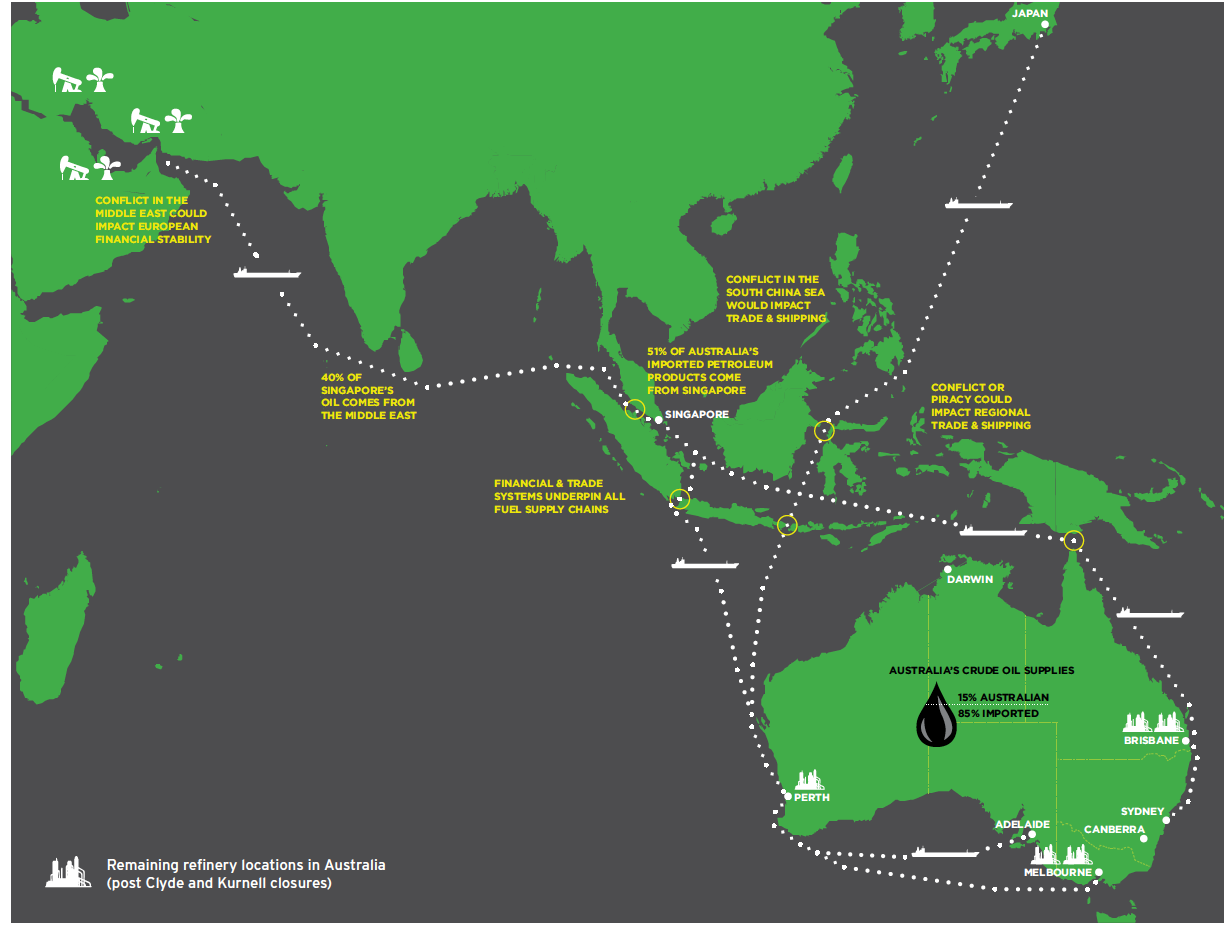

As an island continent at the bottom of the Asia Pacific region, Australia is heavily dependent upon liquid energy imports and with a rapidly disappearing domestic refinery production capacity, these imports necessarily are with regard to refined end products as well.

In reports produced in 2013 and 2014, Air Marshal (Retired) John Blackburn has highlighted the challenges for Australia and the importance for Australia to reshape its energy approach to avoid an inevitable crisis flowing from its situation of energy dependence. The rest of this article is drawn from Blackburn’s reports.

The combination of diminishing refinery capacity along with over-reliance on a stable flow of imports from Asia, the Middle East and North America, has led to a situation where no country would wish to be: Australia currently possess the equivalent of only 23 days of actual consumption of liquid fuels in country at any one time.

This means that the country is subject to significant disruption. Beyond the question of the disruption of supply from an unstable Middle East, there is the direct impact of any disruptions in Asia itself.

As of 2011, Singapore provided 51% of Australia imports of petroleum products.

In the wake of the new Defence White Paper, there is growing focus of attention on the energy security challenge.

In a piece by Malcom Sutton published by ABC News (Australia) regarding the White Paper and the challenge:

With the Government expected to release its latest Defence White Paper on Thursday, an adviser to the country’s largest motorist association has said he hopes tensions in the South China Sea have forced a re-think of where Australia gets its fuel.

Retired Air Vice Marshall John Blackburn said Australia’s food, water and medicine distribution was entirely reliant on transport fuel and the supply operated on a “just in time” philosophy for the sake of logistical efficiency.

Mr Blackburn, who is commissioned by the National Roads and Motorists’ Association (NRMA) to provide consultancy and strategic advice on Australia’s fuel security, said this unerring drive for market efficiency had led to four of the country’s seven oil refineries closing down in three years.

“We’re heading towards 100 per cent import dependency,” Ret. Air Vice Marshall Blackburn said.

“But when the British were passing 40 per cent import dependency, they said they had a national security concern.”

University of New South Wales Professor of International Security Alan Dupont agreed that Australia’s growing dependency on imported fuel was “obviously a vulnerability”.

“We don’t have much in the way of refinery capacity in Australia right now and we don’t have much in the way of strategic stock piles,” he said.

“I think that dependency is only going to increase.”

The South China Sea is a shipping route through which a large proportion of Australia’s refined fuel is imported, including diesel, unleaded and jet fuel.

It is also emerging as a hot zone for potential conflict as China, the United States, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines become increasingly invested in territorial disputes over islands in international waters.

Mr Blackburn said a scenario of conflict in the region and how it would affect Australia’s fuel security was not considered in the Government’s National Security assessment, “upon which the Energy White Paper (EWP) bases its assessment,” Mr Blackburn said.

“The fundamental assumption they’ve made is because we haven’t had a problem in 30 years, we’re not going to have a problem.”

With last year’s EWP offering only brief discussion of the reliability of fuel imports, Mr Blackburn said he expected the Defence White Paper to look more “closely” at the issue…..

In late 2014, Al Qaeda reportedly published a map of critical petroleum shipping routes for the West, including routes between the Persian Gulf, Singapore and Australia.

It prompted warnings from the NRMA and the likes of Senator John Madigan, all of who have been critical of the steady decline in Australia’s oil refining capacity.

The Australian Automobile Association told the Senate inquiry a major disruption to transport fuel supplies would be felt “across society and in every sector of the economy”.

The NRMA and Fusion Australia suggested that even a 20 to 40 per cent cut in the fuel supply, “brought about by factors such as conflict, would quickly lead to a situation whereby the country would start running out of food and medicines, while the economy would start to shut down”.

The Senate inquiry concluded there was no capacity for emergency reserves in the form of government-held or compulsory industry stocks of Australian fuel because its storage capacity was held within the supply chain.

It reported there was no mandate for industry to report fuel stock holding levels because their focus was entirely on a “just-in-time” security of supply to keep costs down.

It recommended a “whole-of-government risk assessment”, which would consider vulnerabilities due to military actions, acts of terrorism, natural disasters and industrial accidents.

And during Senate debate in Australia on February 25, 2016, the question of energy security was discussed by the Minister of Defence directly.

Senator MADIGAN (Victoria) (14:26): My question is to the Minister for Defence. Before the government commits to $30 billion of expenditure: a well-equipped defence force could become a museum exhibit if it cannot be supported by adequate logistics in a time of conflict. There are serious concerns about the ability of our defence forces to have a guaranteed supply of fuel in a conflict scenario, given the fact that Australia has no government owned fuel stocks and does not mandate minimum stock levels for industry to hold. Fuel security is the job of government.

How would the government respond to a direct attack on our fuel supply lines?

Senator PAYNE (New South Wales—Minister for Defence) (14:27): I thank senator Madigan for his question.

There have been a number of discussions recently, and most recently I saw former Air Vice Marshal John Blackburn making some observations in relation to this.

Significantly, while Defence is indeed able to meet its fuel requirements through its own stockholdings, it is important to note that we do in fact a have a number of other supply options.

Amongst those I would indicate that we have arrangements with our closest allies, who can be relied on should there be an interruption to the general supply of fuel.

I understand also in response to Senator Madigan’s question, particularly in relation to logistics support, that this is an aspect of the white paper, to which I would draw senator Madigan’s attention.

It is an area of enabling capability within Defence that has been significantly underfunded in recent years, and it is one which this white paper most importantly seeks to address and in fact readdress.

Hansard Madigan Def WP Fuel 25 Feb