By Robbin Laird

The PRC is combing military with economic with political warfare means to expand its global reach.

In the words of Ross Babbage, the PRC and Russia are focused on making the world safe for authoritarian states.

Information Warfare and the Authoritarian States: How Best to Respond?

As the context within the Pacific changes, Australia, Japan and the United States will shape ways and means to work together to shape a containment belt against the Chinese projecting power and disrupting what is often called the rules based order.

The latest Pentagon report on Chinese military power provides an update on key developments as well as critical challenges, which the Chinese authoritarian state poses to the liberal democracies.

The report provides a compressive overview, but I want to highlight a small number of items.

One of the most interesting pieces in the report is contained at the end of the report and his entitled: “Xi Jinping’s innovation-drive development strategy.”

The piece underscores the significance of an ongoing innovation strategy for shaping an innovative military industrial complex.

China’s push for leadership in global S&T development comes at a time in which dual-use technology advances, applicable for both commercial and military purposes, increasingly occur in the commercial sector.

This means that efforts by China to cultivate a broad base of S&T talent, particularly given its stated focus on dual-use sectors, will be relevant to China’s military power in coming decades.

Specific examples include advanced computing, essential for weapons design and testing; industrial robotics, potentially useful for improving weapons manufacturing; new materials and electric power equipment, which could contribute to improved weapon systems; next generation information technology, which could enable improved C4ISR and cyber capabilities; commercial directed energy equipment, which could contribute to the development of directed energy weapons; and artificial intelligence, which could contribute to next-generation autonomous systems such as missiles, swarming technology, or cyber capabilities.

The report describes an overall force modernization strategy for China, but also identifies some innovations in concepts of operations different from what the US and its allies in the Pacific are focusing upon.

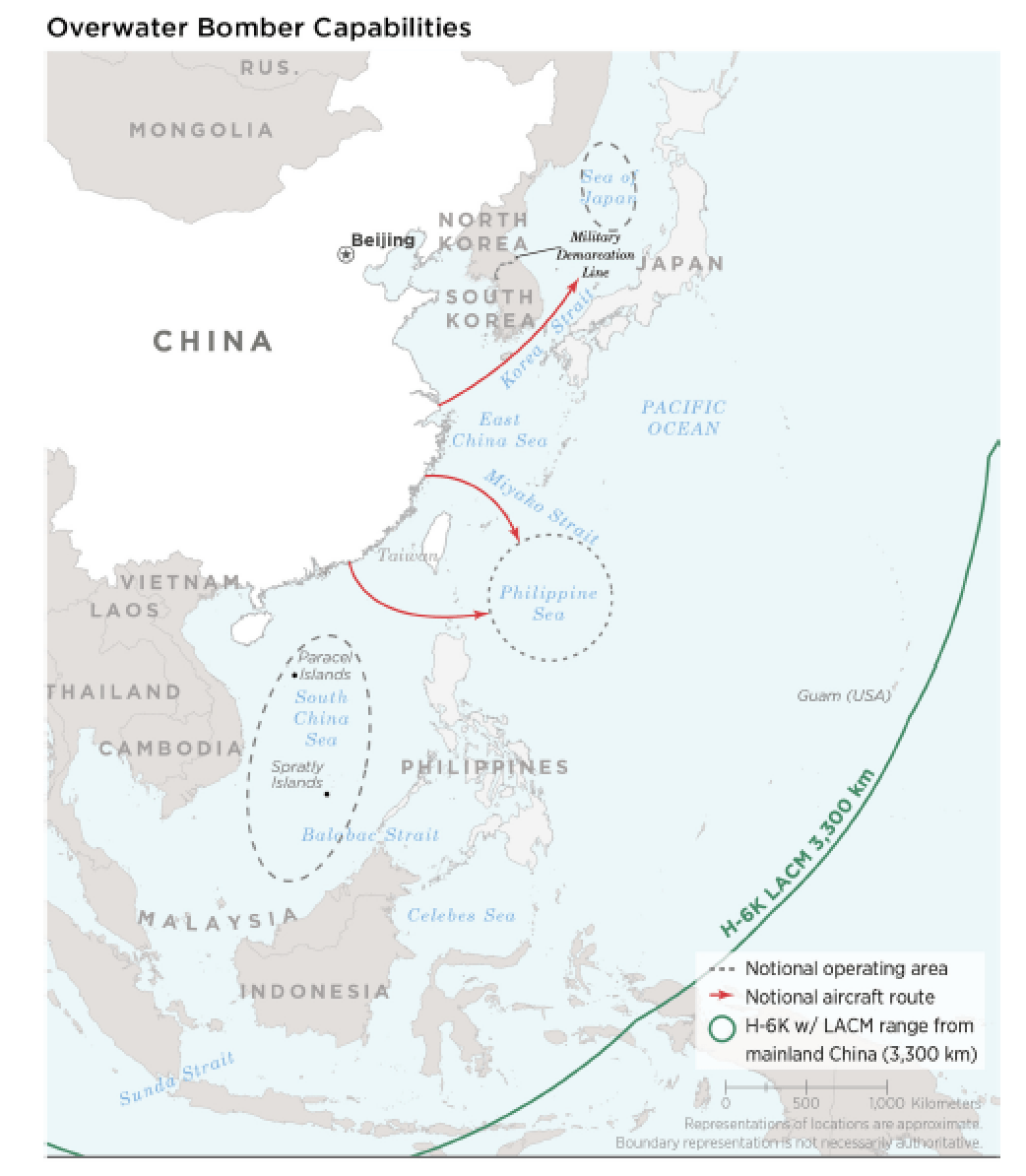

A case in point is the importance laid on using bombers in a maritime strategy.

A case in point is the importance laid on using bombers in a maritime strategy.

The PLA has long been developing air strike capabilities to engage targets as far away from China as possible. Over the last three years, the PLA has rapidly expanded its overwater bomber operating areas, gaining experience in critical maritime regions and likely training for strikes against U.S. and allied targets.

The PLA may continue to extend its operations beyond the first island chain, demonstrating the capability to strike U.S. and allied forces and military bases in the western Pacific Ocean, including Guam.

Such flights could potentially be used as a strategic signal to regional states, although the PLA has thus far has not been clear what messages such flights communicate beyond a demonstration of improved capabilities.

A third key issue discussed in the report is the effort to shape a more effective joint force, which can be used in a peer-to-peer conflict.

As the Chinese have not engaged in land wars far from their area of strategic interest, they have been investing in relevant capabilities for peer-to-peer conflict.

The PLA is a historically army-centric organization, and bureaucratic intransigence has for years limited the PLA’s ability to transform itself into a modern joint force. Beginning in 2015, the execution of PLA reforms are addressing this need, as well as critical related issues such as institutional intransigence borne of corruption and the parochial interests of senior PLA leaders.

In addition to strengthening Party control over the PLA, China’s leaders directed a complete restructuring of the PLA headquarters to strengthen CMC administrative control of the PLA and to establish a joint command system capable of organizing and directing operations on a routine basis…..

Reforms in 2017 and the resulting restructuring of PLA forces have highlighted the PLA’s vision for the future of PLA combat operations. They included the disestablishment of five group army headquarters, the reorganization of many divisions and regiments into combined arms brigades, and the formation of some air assault brigades. A PLANMC headquarters was established and the Marine Corps is tripling to seven brigades across all three naval fleets. The PLAAF reorganized its Airborne Corps into nine brigades, established additional air bases, and restructured its fighter and attack divisions into brigades subordinate to the new bases.

To standardize training, operations, and equipment development, the PLA is also reorganizing its system of academies and research institutions. Organizations have been realigned to enable joint oversight and management of equipment research and development to create efficiencies in the acquisition system. Joint operations and warfighting concepts are being infused into academic curriculum, targeting mid-level officers, to enhance joint interoperability and command proficiency.

PLA leaders are also revising personnel and promotion systems to reduce nepotism, broaden the experience of PLA officers, and encourage and grow operational experience.

The PLA will likely face challenges in fully implementing these reforms, foremost of which is to sustain their scope and pace amid senior leadership transitions and expanding PLA missions. Their success likely depends greatly on strong centralized leadership and direction that can dispel inter-service rivalries, guide and assess organizational change, and influence corresponding reforms in China’s defense industrial base and other supporting institutions.

To capitalize on joint organizational reforms, the PLA will probably need to field significant quantities of new weapons and communications systems required to operationalize its combined operations warfighting concepts.

Finally, as China’s leaders pursue their ambitions for a more globally deployable strategic force, the PLA will need to develop the doctrine, institutional structures and procedures, infrastructure, and platforms to project, support, and sustain forces abroad – all of which appear relatively nascent today.

Clearly, the liberal democracies need to build a comprehensive strategy to deal with a modern authoritarian state clearly focused on expanding its influence, leveraging the weaknesses of our societies, and our proclivity to believe that globalization somehow lead to global freedom and inevitable human progress.

We need to stop being effectively Rousseauian with regard to China.

We need to shape a SIOP designed to counter the Chinese and learn to stress their societies to expand our influence.

And we should re-engage with Taiwan as part of the overall effort to shape a more deliberate strategy towards the China that is evolving, rather than seeing the China we hope will be there one day.

For a report, which focused on ways to counter the Chinese strategy by shaping a SIOP approach see the following:

To read the full report see the following:

https://media.defense.gov/2018/Aug/16/2001955282/-1/-1/1/2018-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT.PDF

Or the report can be downloaded here:

2018-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT

Appendix

In a 2013 piece written prior to the publication of our book on the remaking of American military power to deal with dynamics of change in the Pacific, I laid out a way to look at the evolving Chinese challenge which I think underscores the comprehensive nature of the challenge and how to shape a way ahead.

2013-04-07 The rise of China in the last 20 years is a significant global event.

The challenge for the next twenty is to understand how Chinese military power is intertwined with Chinese power projection and how the West and Asia will respond.

But a key element is simply to understand the challenge of how the military dimension fits into the Chinese global presence.

In the accompanying brief, the Second Line of Defense team has put together a way to understand how these different variables are coming together and evolving over the next 20 years.

We start with the question of three ways forward or how the PRC can built out its capabilities.

The basic bottom line is that the Chinese are clearly trying to extend reach from a more secure homeland base.

And they’re doing this in a couple of different ways; one way is building their nuclear deterrent by having a more survivable force hidden in tunnels and deployed via mobile systems.

And at the same time, they are building what is referred to as anti-access, anti-denial capabilities, which at this point in history, is largely is an extension of the homeland.

They are trying to secure the area from which they can operate over time.

This provides them then with a base; the policy is based on the concept that adversaries will accept the sanctuary and demonstrate a lack of interest or capability in intruding into the sanctuary.

It forms the basis for projection power further into the Pacific and the South China Sea up into Japanese waters, up to the Arctic and towards the Malacca Straits and further south.

The question then becomes the approach being shaped to project power into the maritime zones ultimately for the Arctic and for the great royal route to the south.

Traditional power projection tools are being built for these purposes whether they be carriers, airlift, tanking, bombers, long-range missiles. A variety of Chinese tools are being built to allow the Chinese over time to project power as the United States has understood this over the last 30 to 40 years.

And in fact, the Chinese are following a U.S. model in some respects, that is to say, a very linear air and maritime model using AWACS, using integrated strike packages, and carrier battle group kind of thinking.

But the third level could be understood as leveraging technologies and thinking about the future of power projection very, very differently.

In the interview we did with Mark Lewis, he referred to how the Americans built the USS constitution and that class of frigates in a very innovative way that surprised the British.

We are assuming that some of these game-changing technologies, whether they be hypersonics or innovative use of global ISR assets, space-based e.g., could shape a new approach for the Chinese.

In other words, the Chinese are building out Chinese military power through a building block approach.

By 2030 or so, they will certainly have a global power projection force, but in the interim period, they are focused on securing a sanctuary and building from the sanctuary outward into the Pacific.

In addition, the global exports of aircraft, missiles and other very exportable technologies will allow the Chinese to build global alliances in the military domain.

This is the double bounce idea of the technology; on the one hand, technology comes into China and then is re-exported in the form of advancing products from China.

Regional reach is the key focus in the next decade.

The anti-access, anti-denial efforts are clearly conjoined with a regional reach perspective. That means, in effect, the coming out into the maritime air domains of the Pacific.

However, this is a crowded and dangerous three-dimensional operational space, that is to say underwater, above water, and air-breathing.

And several competitors of China have been already triggered to re-shape their capabilities by concerns about what the Chinese are doing, whether they be Singapore or Japan, or Australia.

To build out a global presence involves a variety of tools coming together and over time, shaping a more integrated force structure package. These include the global exports of missiles, aircraft and capabilities, which allow the Chinese to build out global power relationships as well.

The Chinese are also participating in global missions such anti-piracy to give them the kind of experience of operating abroad far from the homeland, something that they hitherto have had no experience doing.

And this lack of experience for maritime and air reach is a key vulnerability that the Chinese have, of course.

Obviously protecting their engagement in raw materials and transit of goods and services is also a very important aspect of building out capability over time, particularly as the U.S. capabilities attrite which currently is the case as the U.S. has half the size the Air Force it once had. It has a declining number of ships, so there are legitimate gaps in protecting the global commons, which the Chinese will clearly provide and others will see this provision as a legitimate expression of their global role, which it may well be, but all depends completely on how their role plays out.

But what are the critical pieces or the game-changers for the Chinese?

It really is an interaction between a reactive enemy; and in this case, it’s what the West and Asia do in dealing with the Chinese build out.

The Chinese build out is occurring in a very fluid and dynamic strategic environment, and from this standpoint, one needs to look at what are the most critical technologies or capabilities, which are game-changing for the Chinese themselves.

In other words, it is a question of the build out, the technologies, and the strategic environment and the response of others to this environment.

It is a highly interactive. The lack of interactive understanding guides some comments with regard to what the Chinese will be able to do, rather than analyzing what they can do up against what other’s will accept or not accept and what they will do to deny the Chinese with the benefits of enhanced military capabilities.

What actions will be taken by the U.S. or its allies which the Chinese consider the biggest threats to their ascendency?

Which actions will the Chinese target to try to block, and which Asian partners of the United States are most crucial to isolate and undercut in their military modernization efforts to allow for Chinese ascendency?

In our forthcoming book on Pacific strategy, we argue that the U.S./Japanese alliance is the absolute crucial alliance in facing the Chinese in the years to come.

The Chinese military power is coming out into the Pacific and the two greatest naval powers of the 20th century could well become closer together, and this is a major problem facing the Chinese.

And already, the Japanese and the United States have invested in common technologies, Egis, SM-3 missiles and F-35 aircraft, and will seek to integrate this capability in years ahead.

And this integration is a major challenge to the Chinese as the Chinese seek ascendency or an ability to control their environment much further away from the mainland.

In other words, managing the threat is a key part of how you build out military capabilities from a Chinese perspective.

An American-Japanese alliance is clearly a key barrier to Chinese ascendancy.

The Chinese are certainly dedicated to breaking the coalition and its power by undercutting U.S. Military modernization, encouraging the criticisms of the F-35 enterprise, because from a Chinese perspective the F-35 can enable the kind of coalition as can challenge most effectively any Chinese ascendency.

Information warfare involves a set of tools that the Chinese use to try to undercut competitors as well.

The key is to pressure the U.S. lynchpin role in the Pacific to limit what the U.S. can do to reinforce what Asian allies do. It is a Ben Franklin situation where if the allies work together and they work together interactively in the United States, there’s more than sufficient capability to manage the Chinese challenge. If they do not they will have to confront the Chinese challenge largely in isolation from one another.

At the same time, the Chinese are using a diversity of power of tools including information warfare tools to convince folks that there is no real Chinese threat.

Things like the request constantly for transparency from the Chinese, even when the Chinese fly fifth generation aircraft over people calling for the transparency misses the ultimate point that the Chinese are clearly selling the idea that what they’re doing is not threat-based, but it’s a normal projection of Chinese power.

The Chinese power projection effort which is inextricably intertwined with their military is a central reality of the 21st century.

It is a table setter.

How the US, the West and Asia respond will determine the shape of the competition to come.