By Robbin Laird

In visits to the Nordics over the past few years, we have been looking at the return of direct defense and the challenges facing Northern Europe with the shaping of a new Russian challenge. This challenge is hybrid, nuclear and direct.

We have looked as well at Trident Juncture 2018, both from the Norwegian side as well as from the allied side, notably with regard to the USMC and recent interviews conducted at 2nd Marine Air Wing with participants in the exercise discuss their role in direct defense in Northern Europe.

But with the inclusion of Poland and the Baltics within NATO after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a new geographical situation was created within which the defense of Poland and the Baltics became part of the new direct defense challenge. And while the geography changed for direct defense, so did the threat. The Russians have built out new capabilities, notably with regard to strike systems which can bring Northern Europe, the Baltics and Poland under direct and immediate threat in a crisis.

It is not the Soviet days of large rolling ground forces supplemented by air and naval strike forces starring down at NATO and West Germany, it is now a question of isolating and picking off parts of NATO and threatening a wider attack if challenged threat which Putin’s Russia poses.

The Baltics pose a particular problem given that they could get stalled up by an air-ground attack relatively easily by Russian forces.

What then constitutes a credible military approach to Baltic defense that is part of a broader deterrent strategy?

The response until now has largely been about demonstrating commitment through small scale air patrols by NATO nations, rotating ground forces through for training purposes, all of which demonstrate commitment, but fall short of a fully credible defense appraoch.

The response of the Nordics has clearly played a role as well in terms of demonstrating commitment and to revitalizing their approach to direct defense, which certainly plays a role in Russian calculations. Indeed, without a strong Nordic response perhaps the Russians might have already played a much more agressive Baltic intimidation game.

Finland has always played a key role in Russian calculations towards the Baltics, and the Finns have been very clear about their response to Russian games — they have consolidated their relationships within the Nordic region, deepened their relationships with the US, the UK and other NATO partners, and are undergoing defense modernization, including the acquisition of a new combat aircraft.

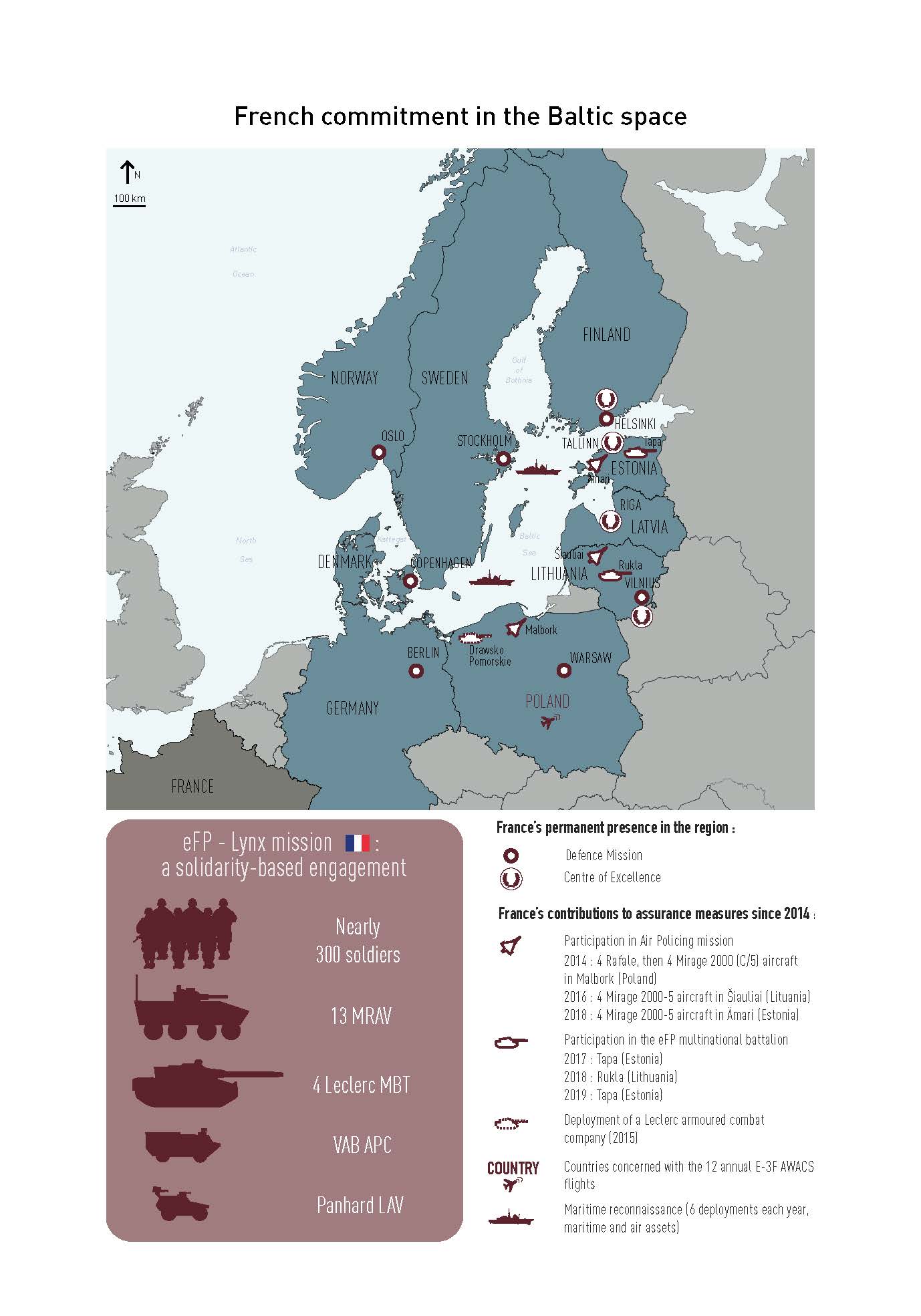

A recent French report published by the French Ministry of Defense highlighted their engagement in Baltic defense and why they take it seriously.

This is how the French MoD describes the challenge:

A partly closed sea, joining the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean after a series of straits, the Baltic Sea accounts for one-third of the European Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and is home to nearly 200,000 French nationals.

Marked by major security challenges, it has seen, over the last decade or so, the revival of tensions forgotten since the end of the Cold War that led to a deterioration of the regional stability.

Brought about by Moscow’s posture, the remilitarisation of the region has spread to all the countries bordering the Baltic Sea. Russia has developed a policy of power assertion and strategic intimidation made of military deployments, threats to use force and use of force on different theatres (Georgia, Ukraine, Syria), as well as international law violations, especially with the annexation of Crimea.

Since 2011, it has modernised its armed forces in the Kaliningrad and Leningrad oblasts and adopted a posture of ‘aggressive sanctuarisation’ by deploying a large number of anti-access / area denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

Along its Western border, Russia has set up a ‘strategic belt’ from the Arctic to the Middle East. In an unprecedented manner since the Cold War, Russia conducts exercises and operations on different theatres at the same time (Baltic Sea, Caspian Sea, Black Sea, Levant). Its maritime presence and airstrike campaign in Syria are both symbols of it.

In reaction, the Allies, including France, have reinforced their protection measures in the East on behalf of their Eastern Allies.

This effort is part of the reassurance mission demonstrating a will and capability to defend the region.

But are such efforts enough to build a credible defense posture?

And let me be clear, this is no criticism of the French but a general challenge facing both the Baltics themselves and their allies.

In a 2015 article, I highlighted what I believe to be the foundation from which credible defense, rather than demonstration of commitment might look like.

With the Russian approach to Ukraine as defining a threat envelope, the question of Baltic defense has become a central one for NATO. And deterrence rests not simply on having exercises and declarations but a credible strategy to defeat the Russians if they decided to probe, push and dismember the Baltic republics.

How can NATO best shape a credible defense strategy which meets the realistic performance of the key stakeholders in defense and security in Northern Europe?

It is no good talking in general deterrence terms; or simply having periodic exercises. The exercises need to be part of shaping a realistic engagement and defense strategy.

As one Russian source has put it with regard to characterizing with disdain NATO exercises:

The West keeps accusing Russia of aggression towards neighboring countries and this is largely bluff in order to make it appear strong, Alexander Mercouris, international affairs expert, told RT.

He suggests it’s a dangerous game because it does bring NATO troops very close to Russian borders.

RT: We’re seeing this massive build-up in the Baltic states, while another NATO member, Norway, is also holding massive military exercises on Russia’s borders.Is the US-led bloc preparing for war?

Alexander Mercouris: No I doubt they are preparing for war, I doubt anybody seriously contemplates war with Russia which is a nuclear power, and it will be a suicidal idea. What I think we are seeing is a show force basically to conceal the fact that Western policy over Ukraine is falling apart, and all sorts of Western politicians and political leaders who made a very strong pitch on Ukraine now find that they have to do something to show that they are still a force to be counted on.

RT: How justified are these claims by some Western officials that Russia could be preparing to test NATO’s resolve by invading a member country?

AM: There is no justification for that whatsoever. Russia has never attacked a NATO-state. It didn’t do so when it was a part of the Soviet Union. There is no threat from Russia to do so, and this whole thing is completely illusory. I’m absolutely sure that everybody in the government, in the West, in NATO knows that very well.

And providing token forces as symbols of intent are not enough as well.

When the secret cables about NATO planning for Baltic and Polish defense were released in the WikiLeaks scandal, a Polish source characterized what he thought of symbolic measures:

Earlier this year the US started rotating US army Patriot missiles into Poland in a move that Warsaw celebrates publicly as boosting Polish air defenses and demonstrating American commitment to Poland’s security.

But the secret cables expose the Patriots’ value as purely symbolic. The Patriot battery, deployed on a rotating basis at Morag in north-eastern Poland, 40 miles from the border with Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave, is purely for training purposes, and is neither operational nor armed with missiles.

At one point Poland’s then deputy defense minister privately complained bitterly that the Americans may as well supply “potted plants’.

The Russians with the advantage of having significant Russian minorities in the Baltics can play a probing game similar to Ukraine if they deem this necessary or useful.

The probing certainly is going on.

Deterrence is not just about arming and occupying the Baltic states in ADVANCE of the Russians doing something and given the geography such actions seem unlikely at best.

As a landpower with significant Baltic sea assets, it is difficult to imagine the Russians providing a long period of warning for the USAF to deliver significant US Army forces to the Baltic states to deter Russian attack. This is not a US Army led operation in any real sense.

And building up outside forces on the ground in the Baltics takes time and could set off Russian actions which one might well wish not to see happen.

This latter point is crucial to Balts as well who would not like to be viewed by the Russians as an armed camp on their borders in times of crisis, and not only the Russians living in Russia, but those in the Baltic republics themselves.

Credible defense starts with what NATO can ask of the Baltic states themselves.

In the 1980s, there was a movement in Western Europe which called for “defensive defense,” which clearly applies to the Balts.

Greater cooperation among the three states, and shaping convergence of systems so that resupply can be facilitated is a good baseline.

Add to that deployments of defensive missile systems designed for short to mid-range operations, and the ground work would be created for a stronger DEFENSIVE capability which would slow any Russian advance down and facilitate the kind of air and naval intervention by NATO which would mesh very nicely with the defensive capabilities of the Baltic states.

In a piece by Thomas Theiner called “Peace is Over for the Baltic States,” he looks at what kinds of actions by the Baltic states make sense in terms of collaborative defense within the bounds of realistic expectations.

The key is not simply to wait for NATO’s so-called “rapid reaction force” to show up in time to view the Russian forces occupying the Baltic states.

Most importantly, the three Baltic nations need a modern medium range air-defense system and tanks.

The air-defense systems currently in service, namely RBS-70, Mistral, Stinger and Grom man portable air defense systems (MANPADS) , do not reach higher than 4-5km and have a range of just 6-8 km.

The three Baltic nations do not need a high-end long-range system like the SAMP/T or the MIM-104 Patriot.

What the core Nordic states (Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland) can do is create a more integrated air and naval defense.

If the Russians believed that the Nordics most affected by a Baltic action could trigger what other NATO nations can do, there is little incentive for them to do so.

This means leveraging the Baltic Air Patrol to shape a Northern region wide integrated air operations capability that the US, France, Germany and the UK can work with and plug into rapidly.

It is about modular, scalable force with significant reachback that would kill a Russian force in its tracks, and be so viewed from the outset by the Russians.

And because it is not based in the Baltics, but the air controllers could well be, it is part of the overall defensive defense approach.

Naval forces are crucial as well, not only to deal with Russian naval forces, but to support the Baltic operation as well. Modern amphibious forces are among the most useful assets to provide engagement capabilities, ranging from resupply, to air operations, to insertion forces at key choke points.

By not being based on Baltic territory, these forces are part of the overall defensive defense approach, and not credibly part of a forward deployed dagger at the heart of Russia argument that the Russian leadership will try to use if significant NATO forces were to be forward deployed upon Baltic territory itself.

Shaping an effective defensive template, leveraging collaborative Baltic efforts, with enhanced integrated air and naval forces will only get better as Western naval and air transformation occurs in the period ahead.

There are a number of key developments underway which can reinforce such a template.The first is the Dane’s acquiring the missiles to go with the sensors aboard their frigates and to position their frigates to provide area wide defensive capabilities which can be leveraged in the crisis.

The second is the acquisition of the F-35 by key states in the region whose integrated fleet can lay down a sensor grid with kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities, which can operate rapidly over the Baltic states by simply extending the airpower integration already envisaged in the defense of the region.

The Norwegians, the Dutch, and possibly the Danes and the Finns will all have F-35s and a completely integrated force which can rapidly be inserted without waiting for slower paced forces has to be taken seriously by Russia. There is no time gap within which the Russians can wedge their forces, for Norway and Denmark are not likely to stand by and watch the Russians do what they want in the Baltics. With the integrated F-35 fleet, they would need to wait on slower paced NATO deliberations to deploy significant force useable immediately in Baltic defenses.

The third is the coming UK carrier, which can provide a local core intervention capability to plug into the F-35 forces in the region and to add amphibious assault capability.

The fourth is that the USN-USMC team coming with F-35B and Osprey enabled assault forces can plug in rapidly as well.

The fifth is the evolving integration of air and naval systems. The long reach of Aegis enabled by F-35/Aegis integration can add a significant offensive/defensive capability to any reinforcement force, and the Norwegians are a local force that will have such a capability.

By leveraging current capabilities and reshaping the template for Baltic defense, the coming modernization efforts will only enhance the viability of the template and significantly enhance credible deterrence, rather than doing what RT referred to scornfully as “US troops drills in Baltic states is more a political than military show.”

A key advantage of the approach is that it is led by the Nordics and gets away from the Russian game of making this always about the US and the “US-led” Alliance.

Putin and his ilk can play this game, but European led capabilities are crucial to reshaping Russian expectations about how non-Americans view their aggression as well.

That was what I wrote in 2015.

And in 2016, the Estonians published a very insightful report on Baltic defense co-authored by three experienced NATO hands: Wesley Clark, Juri Luik, Egon Ramms and Richard Shirreff.

The report focuses upon the importance a credible direct defense capability able to credibly deflect, defeat and deter Russian military forces against the region.

Because the region geographically is virtually indefensible, a credible speed bump needs to be put in front of the Russians providing the time whereby NATO allies can bring significant force to the fight to degrade Russian forces significantly.

The report provides a very good overview of the challenges, the threats and key elements for shaping a credible defense posture in the region.

They argue that the military aspects of deterrence clearly need to be strengthened for a credible appraoch to Baltic defense.

The Alliance must act with a sense of urgency when it comes to reinforcing its deterrence posture in the Baltic states, where NATO is most vulnerable. NATO has too often acted like a homeowner who sets the alarm once the burglars have left. A general change in mindset is needed—a culture of seizing the initiative and actively shaping the strategic environment should become the Alliance’s modus operandi. The Alliance’s decision-makers and general public must realise that the costs of credible deterrence by denial pale in comparison to the costs of deterrence failure.

The authors then address in the report the question of how to strengthen the military aspects of deterrence.

The transition at the Warsaw Summit from assurance to deterrence must be made credible with a more substantial forward presence in the most exposed NATO Allies and an effective coun- ter-A2/AD strategy. While the Baltics are sometimes compared to the West Germany of the Cold War, deterrence by denial is more important today than it was then. It is also feasible because deterrence by denial can be achieved without establishing parity with the opposing forces in the region. We do not need to match Russia tank-for-tank in order to have a deterrent effect.

While we agree with both the former and current SACEURs, Generals Breedlove and Scaparrot- ti, who would prefer permanent forces in Europe, the debate about permanence should not be at the forefront if the continuous presence of combat-capable forces can be ensured through rotation.

The Alliance must deploy, as a minimum, a multinational “battalion-plus” battle group with a range of enablers and force multipliers in each of the Baltic states, with one nation or an estab- lished multinational formation providing its core. Together with the additional US Army pres- ence, which should also be built up to a battalion size in each Baltic country, such a NATO force would be able create a “speedbump” for Russia, and not act only as a “tripwire”.

The Warsaw Summit is not a final destination. NATO must continue efforts to ensure that this posture expands the range of its deterrence and defence options and limits Russia’s freedom of action. The Alliance should continue building its forward presence towards a multinational brigade in each of the Baltic states.

While land presence has gained much attention in the run-up to the Warsaw Summit, the mari- time and air dimensions of NATO’s deterrent posture, as well as the availability of key enablers, have been less touched upon. After the Warsaw Summit, these issues need to be addressed.

Quick reinforcement of the Baltic states by the Allies should be made more credible by pre-po- sitioning equipment much closer to the frontline than 1,600 km away from it as currently planned. During the Cold War, this distance was only 300 km. We recommend that at least a battalion-worth of heavy equipment be pre-positioned in each Baltic state in order to be able to surge the presence of Allied troops rapidly when necessary. The former REFORGER exercises should be revived under the name REFOREUR (Return of Forces to Europe).

NATO’s nuclear deterrent should be strengthened by signalling to Russia that Moscow’s strategy of using sub-strategic nuclear weapons to de-escalate conflict would be a major escalation and would warrant the Alliance’s nuclear response.

An approach should be adopted to cyber weapons similar to the existing one on nuclear weap- ons, stating that the Allies’ offensive cyber capabilities have a deterrent role even if NATO as an organisation does not pursue an offensive cyber strategy. Removing cyber offensive option is tantamount to someone taking away kinetic options from an artillery commander on a battle- field.

NATO must signal to Russia that, in case of aggression against any NATO Ally, there is no such thing as a limited conflict for the Alliance, and that it will contest Russia in all domains and with- out geographical limitations.

North American and European Allies should state that they will act individually in anticipation of NATO, should the Alliance’s collective military response be delayed. The Allies should underline that an individual response is, in fact, a legal obligation that they take seriously, and have plans and units allocated for this purpose.

NATO’s plans should take into account the possible contribution of Sweden and Finland. The Al- liance should also conduct prudent planning for assisting these countries, as a way of reassuring them that their support for NATO would not leave them exposed to Russia’s punitive military action.

In short, as the Russians re-calibrate the use of their military force for both political purpose and combat success, the US and its allies need to do no less.

The featured photo shows thirty maritime units ships from 12 nations maneuvered in close formation for a photo exercise, June 9, 2018, during Exercise Baltic Operations (BALTOPS) 2018 in the Baltic Sea.

BALTOPS is the premier annual maritime-focused exercise in the Baltic region and one of the largest exercises in Northern Europe enhancing flexibility and interoperability among allied and partner nations.

(U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Justin Stumberg/Released)

(June 9, 2018)

For the French report on the Baltics, see the following:

Plaquette DGRIS_France and the Security Challenges in the Baltic Sea Region_vENGFor the report published by the Estonians, see the following:

ICDS_Report-Closing_NATO_s_Baltic_Gap