by Paul Bracken

The failed “denuclearization” summit held in Hanoi between the United States and North Korea took place just as a border flare up played out between nuclear-armed Pakistan and India. So it’s easy to warn in vivid — and realistic — ways about the danger of nuclear war.

It’s easier still to call for an end to the madness of nuclear weapons. This point of view has its merits. It shows that one’s heart is in the right place. But let’s not overlook how recent efforts to abolish the bomb have hit a complete dead end, as North Korea, Pakistan and India demonstrate.

Doubling down on calls to get rid of the bomb is just as likely to go nowhere as it has with these and other countries. It makes us feel good, but it distracts us from more serious efforts to get through this second nuclear age in one piece.

After the Cold War, the overwhelming policy emphasis in the United States and Europe was on arms control and nuclear nonproliferation. Nonproliferation especially had wide backing. It had more support than any other policy, whether economic, educational or environmental.

In those fields, there were disagreements over goals and the ways to reach them. But there was no such squabbling when it came to nonproliferation and reducing the role of nuclear weapons in American defense. Hawk, dove, Republican, Democrat, liberal, conservative — it didn’t matter. All were on board to oppose nuclear arms.

U.S. nuclear weapons were cut by two-thirds after the Cold War. In the late 2000s, the abolition of all nuclear weapons seemed to be coming. President Barack Obama advanced such a plan in a 2009 speech in Prague.

The foreign policy establishment backed it: Henry Kissinger, George Schultz, Sam Nunn and William Perry all supported “global zero” — the elimination or very sharp reduction of nuclear weapons for all countries, including the United States.

Academics, think tanks and intellectuals quickly jumped onto the bandwagon. For a time, it really looked like there was going to be an antinuclear turn in U.S. strategy.

I disagree with those who argue that the effort to get rid of the bomb was never serious. There’s a long history of such disarmament proposals, true enough.

At the dawn of the nuclear age, the 1948 Baruch Plan to put all nuclear weapons under U.N. control was never considered anything but a propaganda stunt by Washington. It was a way to make the Soviet Union look bad because we knew they would reject it.

Likewise, Ronald Reagan’s awakening to the horrors of nuclear war wasn’t really a practical plan. It was quickly derailed by the Pentagon.

The abolition movement of the 2000s was different. Largely because banning nuclear weapons, or sharply reducing their role, locked in U.S. conventional advantages. In the 2000s, the U.S. technological edge still looked certain.

So nuclear abolition — seen from Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang — looked like a way to make the world safe for U.S. conventional strong-arm tactics. No one else had the global, lethal military reach of the United States. So getting rid of the bomb made sense, at least to many Americans.

So why did the effort to get rid of the bomb, or sharply cut back its significance hit a dead end? Because the world changed, and the United States didn’t have enough power to stop the changes. Trying to get North Korea, Pakistan, India or Israel to “denuclearize” wasn’t in the cards.

No arms control treaty was going to restore the world of 1975, when two big superpowers could run the planet on nuclear matters. It wasn’t lack of will, partisan politics or a military industrial complex that derailed nuclear abolition.

It was the international order changing in natural ways, as sovereign states could pretty much do what they wished inside their own borders.

This is the nub of the problem. It’s the real reason that a movement with wide public support, bipartisan agreement and grudging Pentagon backing, nonetheless, hit a dead end.

The 2000s, seen from Russia, China and North Korea perspective, posed a mortal danger: a technologically dominant United States that would be unrestrained by the risk of an “explosion” to massive destruction from nuclear weapons.

Others — Israel, India and Pakistan — didn’t like the anti-nuclear shift either, as they might be victims of conventional attack.

Today, the major powers — the United States, Russia and China — have strategic nuclear modernizations programs underway. U.S. policy is responding to this change. There’s a return to a nuclear emphasis, whether anyone cares to say so or not.

Nine countries now have the bomb, and a prudent bettor would likely put his or her money on this number going up, not down.

But I would bet on something else as well: Arms control will come back. Right now,the price of “arms control stock” is in the basement, true. But let’s not forget that it’s been there before. In the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and in the Reagan nuclear build-up of the 1980s, its price was even lower.

Yet arms control came back both times. And it will again. Why? Because it has to. In these earlier episodes, the dangers of the arms race itself were seen as greater than those of falling behind the enemy.

With nine nuclear weapons states today and big nuclear modernizations underway, at some point the dangers will force the big powers to understand the same thing. No one can say whether there will be a happy ending to the arms race. I can imagine a wide range of possibilities here, except one: disarmament.

Paul Bracken is a professor of management and political science at Yale University.

This article first appeared in The Hill on March 19, 2019 and is republished with permission of the author.

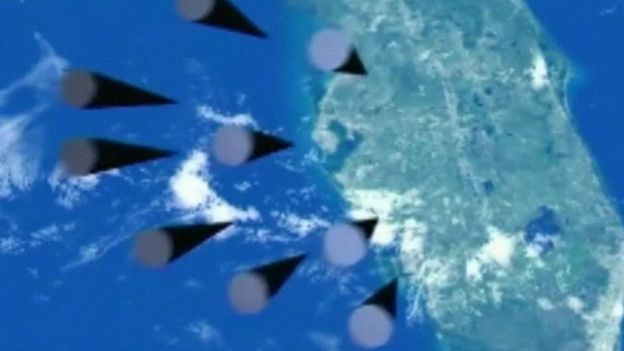

The featured photo shows one of the video graphics appeared to show missiles dropping on the US state of Florida during a Putin presentation on the nuclear capabilities of Russia against the United States.

The last time we had a KGB leaders in charge of Russia we faced a significant nuclear crisis management challenge.