With the strategic shift, the importance of regional conflict, and of regional allies is enhanced within the overall context of full spectrum crisis management.

And with it, the need for enhanced self-reliance of allies as well.

But enhanced self-reliance in the context of dealing with global authoritarian challenges for the liberal democracies, their partners and allies requires a balancing act.

On the one hand, the regional partner or ally requires access to the force capabilities and the industrial underpinnings of those capabilities evident in a relatively small number of defense industrial powers. And this entails the capability to plug and play between the larger power and the regional partner or ally.

On the other hand, there is a growing need for indigenous industrial support for sustainment and the development and production of selected national or regional defense capabilities by regional partners or allies.

It is not a zero sum game, but does challenge the dichotomy of exporting and importing nations for more advanced equipment.

It is about how the regional partner or ally can shape enough sustainability and defense capability within the boundaries of its nation or regional setting to be able to work with a larger ally who needs to plug and play with the capabilities of that nation.

In our work with the Williams Foundation, the Australians are clearly working to enhance their sustainability and industrial infrastructure to support the evolution of their integrated force.

But clearly they are not alone.

In a recent piece published by our partner Front Line Defence,Brett Boudreau, a retired CAF Colonel, a Fellow with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, and former Director of Marketing and Communications at CADSI (2013-14), assessed the presence of Canadian firms at the International Defence Exhibition and Conference (IDEX) at the National Exhibition Centre in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

In so doing, he underscored the evolving trend and the challenges which this trend posed to Canadian industry:

One important take-away from IDEX with strategic consequences for Canada is how aggressively Saudi Arabia and the UAE alone and in partnership, have pursued strategies to substantially expand their respective homegrown defence industries.

Vision 2030 sets out Riyadh’s ambition for at least half of the national security and military equipment it needs to be produced locally by 2030, from about 2 per cent now.

To help achieve that, the state-owned Saudi Arabian Military Industries (or SAMI) was stood up in May 2017, and was already a major exhibitor at IDEX 2019. Chief Executive Andreas Schwer, in an interview with Reuters at a conference on the margins of IDEX, said SAMI “will generate 30 per cent of its revenues from export markets by 2030” and generate $10B in revenue over the next five years, aiming to create more than 40,000 jobs locally by 2030.

Schwer also said since 2018, SAMI had signed 19 joint venture deals with companies [none Canadian] and planned to sign 25 to 30 more in the next five years.

Emirati national leadership is also not shy to dream boldly, to set out long-term development visions, and to aggressively pursue ideas that seem fantastical at the time, be it in fields of tourism, transport or even space.

For instance, in 2014 the Dubai International Airport overtook London’s Heathrow to become the world’s busiest for international travellers, with more than 88 million passengers in 2017, up from 16 million in 2002, according to the airport authority. Dubai’s Expo 2020 expects to welcome at least 25 million visitors.

The five-decade-long national development vision – Centennial 2071 – has as its ambition nothing less than to make the UAE “the best country in the world”, with a focus on education, economy, government development and community cohesion. The emphasis on higher education and the application of advanced technology is at the heart of many national priorities and projects. The world’s first commercial hyperloop transport system – using electro-magnetic levitation to propel the capsule to speeds in excess of 1,100 km/h, is in production and will eventually link Abu Dhabi, Al Ain and Dubai in a 150-km network at a cost to build of $20-40M US per km, with the first 10 kms expected to be ready this year.

Last October, the UAE’s first locally-made satellite was launched into orbit from Japan, just one offshoot of the National Space Strategy 2030 to turn the country into a major global hub for space-related science and technology. The UAE will send its first astronaut to the International Space Station in 2019 (two are in training now), as well as a probe to Mars in 2020. In 2017, the UAE unveiled a 100-year plan to establish a colony on Mars by 2117 (!) – and are building a simulated prototype Mars colony in the desert: according to the Emirati project manager, the prototype 1.9 million square feet Mars Science City near the Mohammad Bin Rashid Space Centre, will be 3-D-printed and operational in four years.

So, when leadership including Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, says the country wants to transform its defence industry to realize multiple strategic objectives in short order, we can expect that a national defence industrial strategy currently being developed will have big ambitions and heft behind it.

This muscular approach to a made-in-UAE defence industrial strategy is visible also by the upcoming exhibition schedule in the country.

Later this year is the Dubai airshow, and in early 2020, the Unmanned System Exhibition (UMEX) for drones, robotics and unmanned systems – the only one in the Middle East – and the Simulation and Training Exhibition (SimTEX) for defence, civil aviation and healthcare in Abu Dhabi, expected to draw 12,000 visitors and 120 international exhibitors.

Comparing national efforts at a premium show like IDEX provides a stark visible contrast of different national strategies and approaches to indigenous defence and security industries.

“You can see it here at the exhibition and conference,” said one Canadian business representative.

“Some nations don’t look to be trying very hard at all, some look to be trying, some are serious, and some are really serious. At the very least, Canada should wish to move from the ‘look to be trying’ to the ‘we are serious’ category.”

“What we’ve seen in other nations is the nut we have to crack,” says Cianfarani. “We can keep talking about icing all these little cakes that we have now in Canada, but I do not believe they will make the tremendous impact in little bits and pieces that you get with a $15B [General Dynamics Land Systems] sale.

“The fact is 80% of the revenues driven by the industry are from less than 10% of the companies.”

To make a substantive difference in the industry, she says, “you’d have to pick five to ten major domains or procurements and go after them hard as a nation. You’d have to go after them like the French do, like the Germans do, like the UK does.

You’d have to mobilize the politicians, you have to mobilize the military to some extent [attaches] as sales people.”

That is particularly the case in Defence, she explains, since that is a marketplace that by definition is considerably more managed compared to other sectors such as IT.

“What we would love to see,” says Cianfarani, “is a contract that gets awarded under the IDEaS program or any other innovation program that’s happening, that actually gets purchased on an active procurement for Canada under the investment plan and then gets supported and promoted by the Trade Commissioners, Canadian Commercial Corporation and Global Affairs as a viable export from our country.”

Walking amongst so much military hardware of every sort imaginable at IDEX, one wonders about Canadian defence industry prospects in the face of focused competition from other countries and strained relations (including the spill-over effect of the Saudi Arabia boycott to its neighbours including the UAE, plus the uncertainties for exports stemming from the Liberal Government’s self-declared “values-based foreign policy”).

The latter doesn’t faze Cianfarani, however.

She says that so long as national leaders are clear about countries they have decided they no longer want to do business with, and why, being in the business of defence exports and having a values-based national foreign policy can co-exist.

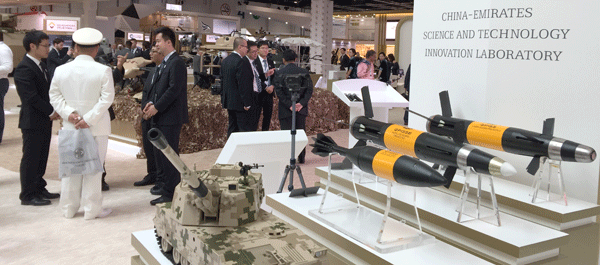

The featured photo highlights one country clearly interested in leveraging the regionalization trend line, the PRC.

The strategic challenge for the United States is clear:

How best to deal with the cross-cutting of two trend lines?

The first trend is the rise of global authoritarianism, something which was not anticipated with the optimistic end of history dominance by liberal democracies.

The second is how best to work the challenge of reworking the industrial base in order to deal with the aspirational dynamics of regional partners and allies for the liberal democracies while maintaining cutting edge capabilities?

How to deal with both trends effectivley?