By Robbin Laird

At the recently concluded Williams Foundation Seminar held in Canberra, Australia on October 24, 2019, the series launched in 2013 to discuss the nature and impact of fifth generation force capabilities in the defense of Australia and its capabilities to work with core allies continued.

At this session, the focus was upon the changing nature of the regional context for Australia and how the fifth generation force needed to evolve to operate effectively in the dynamically changing region and how best to provide for the continuous change which an evolving integrated distributed force clearly needs to gain the decisive advantage needed in a contested region.

The session built from the two most recent sessions where the focus on shaping an integrated distributed force was the assumption based upon which further development of the Australian Defence Force would be built.

The first session last year posed the question of how to extend the reach of the ADF within the region through shaping longer range strike capabilities.

The second session then broadened the consideration to how to enhance the sustainability of the force by shaping a more resilient Australia and enhanced capability for Australian industry and the infrastructure renewal in Australia could be built.

This seminar proceeded from the operative assumptions on how for the ADF to be able to enhance its capability for a decisive advantage when needed within the region and beyond, when necessary to operate alone, or in a leadership role within coalitions, or when contributing to a coalition led by partners or allies.

There were several key themes developed throughout the three sessions during the day, and the upcoming articles on those sessions and the final report of the seminar will provide more detail on the various sessions themselves.

A major theme throughout the day was the nature of the challenging region and the threat calculus facing the ADF. The notion of manoeuvre was taken in a wider sense than simply military tactical advantage and was considered in the wider context of information war and gaining a strategic advantage through political warfare, supply chain dominance or defeating the enemy without firing a shot.

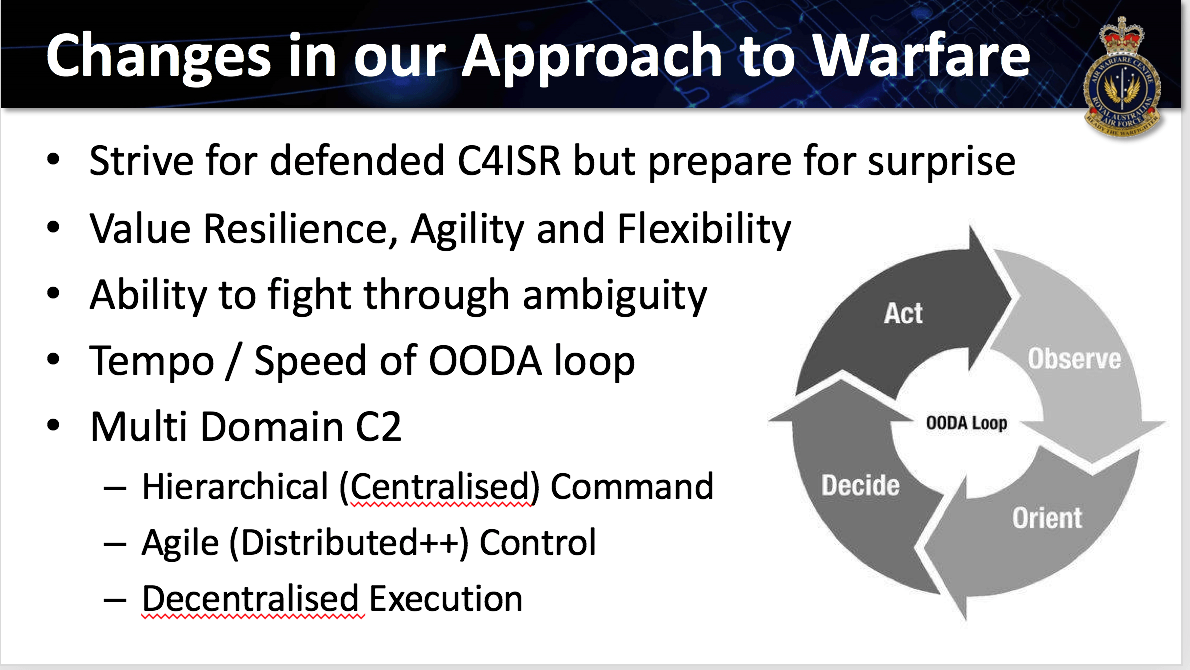

Gaining an information advantage and C2 dominance featured throughout the day as a key part of 21st century manoeuvre warfare, with warfare understood in the wider context in the region where dealing with 21st century authoritarian powers as well as the threats and anomalies associated with 21st century terrorism and analogous challenges needed to be dealt with.

Fifth generation manoeuvre was highlighted in terms of enhancing the ways the ADF in terms of its evolving C2 and ISR operational infrastructure could provide the force with the ability to bring decisive effect to the threat or the challenge.

The head of the Australian Air Warfare Centre, AIRCDRE Phil Gordon, provided the following definition of fifth generation manoeuvre: “The ability of our forces to dynamically adapt and respond in a contested environment to achieve the desired effect through multiple redundant paths. Remove one vector of attack and we rapidly manoeuvre to bring other capabilities to bear through agile control.”

Throughout the day, various speakers provided their perspectives on how to build out the capability identified by AIRCDRE Gordon.

A key contribution came from industry where the evolving relationship between industry and government was the focus of attention. The core point was the need for both industry to work more effectively with one another and with government able to provide a more cohesive engagement with industry to shape the kind of integration which is prioritized by the build out of the integrated distributed force.

One point highlighted was that by linking industry labs more effectively the capability of industry to support the evaluating capabilities for the integrated force would be enhanced.

A case study of how the kind of integration being built might be accelerated was provided by Rear Admiral Goddard, the head of the Maritime Border Command.

Here the level of integration among key agencies in the Australian government are being enhanced with a core focus on dealing with the threats and challenges facing Australian border security, and by being able to deal with threat or challenge at its source.

This requires Australia to bring integrated capability to the effort but doing so with close cooperation with allies and partners.

As Rear Admiral Goddard put it:

Through our capacity as a convening authority, at any point in time I can rely on ADF, AFP, AFMA, intelligence agency, AFP and others unified together for effect; a true Multi-Agency.

The advantages of this unity of effort must be leveraged ultimately at the tactical level, through what I would term Command and not control – Robbin Laird has termed control the ‘legacy approach to hierarchical approval’ and I would tend to agree with his assertion that any advantage on the battlefield we currently have would be negated by a hierarchical approach.

MBC must take advantage of the opportunities afforded from a distributed force to achieve mission success through technological advantages – our future will be through allowing sound decision making at the tactical level through sound connectedness.

By virtue of the nature of the command, MBC is answerable to both the Home Affairs Portfolio and the Australian Defence Force through the Chief of Joint Operations. This in itself has the opportunity to create advantage for the civil maritime security mission; the advantage of operating in the so-called ‘Grey Zone.’

While MBC operations are civil in nature, it has a high end mission – security of our maritime borders – and uses high-end assets to do so; an ideal future would to see the entire spectrum of both civilian and military assets put to the task.

Operating within this grey zone allows MBC to play a large role supporting and engaging a large remit of stakeholders. With regular contact with all facets of government from State/territory up to Commonwealth as well as industry in a supportive role, MBC’s force elements encompass land, sea and air – a unique arrangement in regards civil maritime security, however Australia’s Borders are unique which necessitate this approach.

Reflecting a Fifth Generation approach, the force is scalable dependent on the threat or response that is required and the structure at Maritime Border Command allows this force to fully integrate providing both situational awareness and effect.

With the Maritime Border Command living the transition so to speak, the ADF is working a broader scale transformation of its own which can interact with this real-world experience as well.

And the need for an integrated force built along the lines discussed at the Williams Foundation over the past six years, was highlighted by Vice Admiral David Johnston, Deputy Chief of the ADF at the recent Chief of the Australian Navy’s Seapower Conference in held in Sydney at the beginning of October:

“It is only by being able to operate an integrated (distributed) force that we can have the kind of mass and scale able to operate with decisive effect in a crisis.”

The need for such capabilities was highlighted by the significant presentation by Brendan Sargeant at the seminar where he addressed the major strategic shift facing Australia and why the kind of force transformation which the Williams Foundation seminars have highlighted are so crucial for Australia facing its future.

In the future there will be times when we need to act alone, or where we will need to exercise leadership. We have not often had to do this in the past – The INTERFET operation in Timor, and RAMSI in the Solomon Islands are examples.

We are far more comfortable operating as part of a coalition led by others. It is perhaps an uncomfortable truth, but that has been a consistent feature of our strategic culture.

So I think our biggest challenge is not a technical or resource or even capability challenge – it is the enormous psychological step of recognising that in the world that we are entering we cannot assume that we have the support of others or that there will be others willing to lead when there is a crisis. We will need to exercise the leadership, and I think that is what we need to prepare for now.

To return to the title of this talk: if we want assured access for the ADF in the Asia Pacific, then we need to work towards a world that ensures that that access is useful and relevant to the sorts of crises that are likely to emerge.

I will leave one last proposition with you. Our assured access for the ADF in the Asia Pacific will be determined by our capacity to contribute to regional crisis management. That contribution will on some occasions require that we lead.

The task now is to understand what this means and build that capacity.