By Peter Jennings

Australia has a brilliant opportunity to shape US President-elect Joe Biden’s strategy for the Indo-Pacific in a way that will secure a major increase in American military power in the region. This will be a test of the Morrison government’s agility to move quickly to secure an advantage.

The United States Navy plans to re-establish ‘an agile, mobile, at-sea command’ known as the 1st Fleet, focused on Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean region.

Recently the secretary of the US Navy, Kenneth Braithwaite, told a congressional committee, ‘This will reassure our allies and partners of our presence and commitment to this region.’

Planned to grow to the scale of the US 7th Fleet based in Japan, the 1st Fleet restores a unit disbanded in 1973 at the lowest point of America’s experience in the Vietnam War.

Characteristically, the Trump administration seems not to have raised the idea with Australia or indeed Singapore, mooted as the potential shore headquarters of the fleet, but don’t write this off as a last-minute Trump flash in the pan.

The US has long realised that it needs to lift its naval presence in the Indian Ocean. When Australia negotiated the US Marine Corps ‘rotational presence’ operating out of Darwin, the plan agreed with Barack Obama in 2010 was ultimately to locate some major US warships at the Australian navy base, HMAS Stirling, near Perth.

That trail went dry for some years because our own Defence Department has never met an opportunity it could not squander by prevaricating. It’s time to restart this conversation. We should propose to Biden that elements of the US First Fleet should operate out of Stirling and from the Port of Darwin. If Singapore is reluctant to host a land-based headquarters, then we should offer to be the host.

The way to overcome any reluctance in Washington from a new administration considering adopting a late Trump announcement would be for Australia to step forward and offer to bear some of the cost of hosting these ships.

Make no mistake that there is substantial deterrence value for us to have the US Navy and Marines on our shores, working with the Australian Defence Force. Any country looking to do us harm would have to factor the US presence into their calculations. Moreover, we could aim to have some vessels arrive in 2021—contrast that to the decade and a half we will wait for our new submarines to be launched.

Readers will quickly point out that Washington won’t be thrilled to base ships at the Port of Darwin, leased to a Chinese company in 2015 for 99 years. The idiocy of that blunder continues to get in the way of urgent strategic business.

The Australian government has the power to take the ownership back and it should now work with the Biden administration to make the Port of Darwin and HMAS Stirling the military and strategic hubs they need to be.

A chorus of Beijing’s local fanboys will cry that such an Australian act will offend the Chinese Communist Party. The tone will be wrong, the time is not right, more nuance is needed, let’s pick up the phone and find a party functionary sympathetic to our plight.

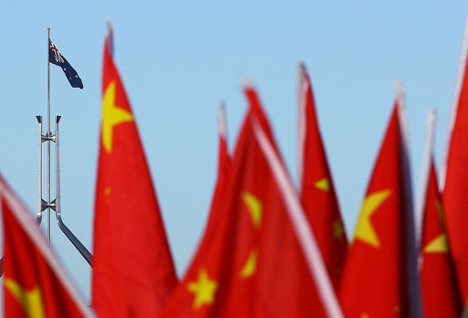

So much of the critique of Australia’s pushback against CCP assertion focuses on tone rather than the underlying strategic trends. What is happening in the bilateral relationship has little to do with diplomacy and everything to do with the fact that China and Australia have irreconcilable strategic aims and interests.

We have just witnessed the angriest week in Australia–China relations. Many seem bewildered that the situation could have got to this point. Does a call for an investigation into the origins of the worst global pandemic and economic crisis in a century really explain why China is now in effect permanently burning its bridges to rapprochement with Canberra?

The CCP’s strategic plan remains opaque, and deliberately so. The 14-point grievance listreleased by the Chinese embassy in late November tells us the issues over which Beijing is unhappy: foreign investment, 5G, anti-interference laws, independent media and noisy think tanks.

None of this explains how China’s leaders think ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy and military sabre-rattling delivers the global leadership they crave and the deference they demand.

For our part, the call is that we must ‘repair’ relations as though we broke the Ming vase in China’s shop. Hold on, weren’t we the ones who were determined to be ‘country neutral’ when cyber spies attacked our national institutions and who cherished (in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s words) our ‘constructive relationship with China, founded on shared interests, mutual benefit and mutual respect’?

At times like this it’s useful to step back to look for the patterns, constraints and opportunities (if any) in the relationship as a way to understand what might happen next.

Economists and strategists use game theory to try to understand individual, company or national decision-making. The ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ requires two non-communicating parties to choose between cooperating or not cooperating with each other. Over repeated games between trusting parties, cooperation gives both sides the most rewards, but between distrustful parties the short-term pursuit of individual interest, where one side benefits at the other’s expense, usually triumphs.

Applied to Australia–China relations, the prisoner’s dilemma offers some insights but not much hope that things can be fixed.

For much of the past 30 years Australia and China cooperated to mutual benefit. Prime Minister John Howard’s formulation for the relationship was that we could choose to cooperate in areas where we had mutual benefit, principally trade, and agree not to make a fuss where the two countries differed, such as on human rights and on China’s approach to Taiwan.

The prisoner’s dilemma was successful because Beijing mostly chose to cooperate. There were occasional breakdowns: the massacre of protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 should have been read by the world as a sign that the CCP had no intention of relaxing its grip on power.

On balance, though, there was simply too much in it for Australia and China to cease cooperating, but the nature of the Australia–China relationship started to change dramatically in the last decade.

At the same time as our level of economic dependence on China was growing and expanding into areas such as education, tourism and foreign investment, Beijing was also dramatically scaling up its military, turning the People’s Liberation Army into a high-technology force.

A turning point was Beijing’s decision around 2014 to annex and militarise the South China Sea. Between 2014 and 2016—exactly the time it took us to produce a defence white paper—China created three airbases and put enough missiles and aircraft into the region to enable it to shut air and sea traffic any time it pleased.

The CCP’s attempts to buy political influence in our federal and state parliaments and its full-on cyber and human espionage efforts in Australia are becoming more visible.

In the prisoner’s dilemma game, China was defecting from cooperation. It saw that it could make major short-term strategic gains by doing so. For much of the last decade, while China was openly and covertly defecting from cooperation, Australia continued to cooperate. Beijing was more than happy to take advantage of our naivety.

Why were we so gullible?

Partly because many officials and politicians had their careers shaped during the long years of cooperation and were too invested in that world to see it being predated away.

Our intelligence focus was too myopically directed towards combating Islamist extremism and too many businesses, universities and state governments were fixated on making Chinese money without knowing or caring about the military and strategic picture.

My view is that there is little that Australia can do unilaterally to persuade China back towards the mutual-cooperation paradigm. That is because China is more strategically important to us than we are to it. It can afford to defect from cooperation.

But we do have options. Australia has four points of advantage in dealing with China. In order of value they are our alliance with the US, our ability to shape how other democracies deal with China, iron ore and, finally, the things we produce that wealthy Chinese consumers like.

The US alliance is what makes Australia strategically relevant to China and hinders its desire to dominate the Indo-Pacific. That is why China constantly attacks the alliance and its defence industry base. Making the alliance stronger, including by hosting the US 1st Fleet, is the necessary response.

Australia constantly under invests in and underestimates our ability to shape how other democracies deal with China.

Beijing hated our decision on 5G not because of the value of the Australian market but because they judged that our decision to exclude Huawei would have an impact on what other democracies would do. That fear is turning out to be well grounded.

Our best hope to push back against CCP coercion is to internationalise the problem, as has happened with 5G, persuading friends and allies that they will be bullied too if we don’t collectively say to China that their greatness can’t be built on a foundation of contemptuous behaviour.

If China could have found a reliable and plentiful source of iron ore other than Australia, it would have made the switch by now. Brazil is unlikely to replace Australia as a stable, cost-effective and long-term supplier. We have a major leverage point if the government is brave enough to step in and start making controls around price and supply.

Demand for other exports like food, wine, timber, education and tourism comes from Chinese consumers. The CCP might see tactical political advantage from imposing bans or tariffs, but it does so at the risk of annoying its own people, from whom the party seeks legitimacy.

These leverage points give more scope for Australia to secure its interests than is widely understood. Capitulation to Beijing is unthinkable. After years of being lulled into complacency, we need some policy imagination and decisive decision-making to secure our future interests.

Peter Jennings is the executive director of ASPI and a former deputy secretary for strategy in the Department of Defence. A version of this article was published in the Weekend Australian.

This article was published by ASPI on December 5, 2020.

Featured Image: Mark Nolan/Getty Images.