By Robbin Laird

Sovereign Australian space requires an Australian industrial space eco-system to be shaped and enhanced.

How might this be done?

Crafting, shaping, and building out an Australian space industry able to provide for sovereign capabilities for the Australian government decision makers is based on the enhanced opportunities in commercial space.

Nick Leake, head of satellite and space systems Optus, provided a comprehensive look back at the company’s experience in the space business. Optus is one of the largest telecommunications companies in Australia. It has operated satellites as part of its business since 1985. Currently, the company operates 10 satellites with Optus 10 being the latest of their satellites.

As noted by the company: “In 2003, Optus successfully launched the world’s largest hybrid commercial and military communications satellite Optus C1, together with the Australian Defence Forces. Optus C1 is the Australian hotbird with twenty four commercial Ku-band transponders operating in beams covering Australia, New Zealand, the nearby offshore islands, Papua New Guinea, Hawaii and South East Asia. Optus C1 carries subscription TV services and Aurora Free-to-Air radio and television services to remote areas in Australia.”[1]

All of this means that Leake spoke from the standpoint of several years of operating experience as an Australian firm with real-world experience in working a commercial telecoms satellite fleet. His discussion focused on the challenges of operating a satellite network in the growing presence of space junk and in the face of powers that believed they had the right through ASAT systems to place deliberate “junk” to disrupt or destroy a perceived adversary’s satellites.

Leake underscored a number of key points about the interaction between commercial space and the need for government to focus on maintain some kind of order for space operations.

“We are looking towards the future. We are looking for some cohesion within Australia with Defence and the Australian Space Agency to develop tools to give us better safety in operating our geostationary spacecraft.

“The C1 spacecraft is 18 years old. We operate that satellite in what they call inclined orbit. So we operate spacecraft at 36,000 kilometers in a 70-kilometer box. We fly it in a figure of eight because it has the pull of the earth, pull of the moon, pull of the sun, so it is never static. We try to keep it in this box, pointing at earth and if you don’t have a spectrum filing, you’ve got nowhere to put your spacecraft. It’s incredibly important that you keep your spacecraft, at your orbital slots and that you maintain those spacecrafts.

“If you move a spacecraft away, you’ve got three years to put that spacecraft back to keep your finding in use, so it’s called bringing into use. That’s an important part of a commercial operator, but it’s even more important for our Defence forces that they maintain their orbital filings across the orbital arcs that they want to use their spacecraft.”

The impact of evolving commercial space for defence and security operations could not be more clear than in the domain of ISR.

In his presentation to the seminar, AIRCDRE Richard Keir (Retd.) Strategic Advisor for National Security and Intelligence to Geospatial Intelligence Pty. Ltd, provided a targeted presentation on how the ISR demands for the civil, security and military sectors can benefit from commercial geospatial efforts.

There are a number of conclusions one can draw from the emergence of a robust commercial space enabling ISR Market.

Notably, since 2002, the commercial space-based earth observation market has become very dynamic and global. Essentially, Australia is involved in this market and there are clear opportunities for the Australian government to get better value out of this market for it national security requirements. In effect, commercial imagery and data from that imagery can be used along with classified sources and methods and thereby enhance the scope and quality of the data collected.

By taking advantage of the growing number of commercial satellite capabilities and constellations, the Australian government can enable a whole of government strategy in defence and security. Because commercial space based ISR data and information is unclassified, it can form a solid foundation for information sharing with a wider array of allies and partners than highly classified imagery. This can prove very useful in terms of crisis management and escalation control, notably as information war is a core reality today.

For example. in discussions I had during my past visits with the Maritime Border Command, it is very clear that such capabilities fit right into their evolving approach to working from maritime domain awareness shared with partners and allies.

The Maritime Domain Awareness dynamic is an arena where shared information s crucial for both whole of government and working with partners and allies. In the recently released White Paper which Keir referenced in his presentation which his company just released, the nature of the MDA market for commercial space is explained in the following terms:

“MDA is enhanced by space-based Earth observation as it has unique capabilities to image large swathes of the ocean and complex littoral environments using a mix of EO, IR and SAR imaging sensors – fused with AIS – and increasingly assisted by RF sensors. The latter assistance provided by RF sensors is especially useful in cases where a vessel has not enabled its AIS or has deliberately mis-characterised itself. RF sensors may provide enough of a clue to tip and cue an all-weather SAR capability or a good weather/daylight hours EO capability to classify or identify the vessel.

“The use of more novel sensors can also prove valuable in MDA. For example, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) is a sensor on board the Suomi National PolarOrbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) and United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) NOAA-20 weather satellites. The sensor has the capability to detect lights on vessels at sea that are often used to attract fish.15

“Because MDA is an international issue that transcends national borders and spans issues of national security through to economic interests, information sharing is often fundamental to its success. No nation can sustain 24/7/365 full situational awareness of the oceans in isolation, so the most efficient way to achieve the desired level of knowledge is to share information with partner nations. Indeed, counterintuitively, national sovereignty frequently depends on the sharing of data, information, and intelligence between likeminded nations to achieve MDA.

“Commercial space-based ISR data is unclassified, has high resolution, and is capable of 24/7/365 availability across the gamut of EO, IR, SAR, AIS and RF. It is therefore of great value to nations such as Australia in its efforts to facilitate the MDA of developing nations because it will generally have fewer constraints on its use.”[2]

The main presentation outlining the current state of the Australian space eco-system and the projected way ahead was provided by Anthony Murfett. Deputy Head of the Australian Space Agency, which was launched in 2018.

The purpose of the Space Agency is “ to transform and grow a globally respected Australian space industry that lifts the broader economy, inspires and improves the lives of Australians – underpinned by strong national and international engagement.” And “the Australian Space Agency aims to triple the size of the Australian space economy (from A$3.9B to $12B) and create an additional 20,000 space jobs by 2030.”

The current situation finds the Australian space business operating at a level of AU$4.6 billion with 11,560 jobs existing across the Australian space industry. The investment in space capability growth is AU$7 billion with AU$800+ coming from investment by the Australian government in civil space and AU$2 billion coming from a pipeline of investment across all the Australian federal states and territories.

Growing civil space provides a significant opportunity to expand the capabilities for the Australian defence sector as there are a number of key areas alignment between the two sectors. Murfett identified four key areas: satellite-based capability and services, Space Domain awareness, Position, Navigation and Timing and Earth Observation.

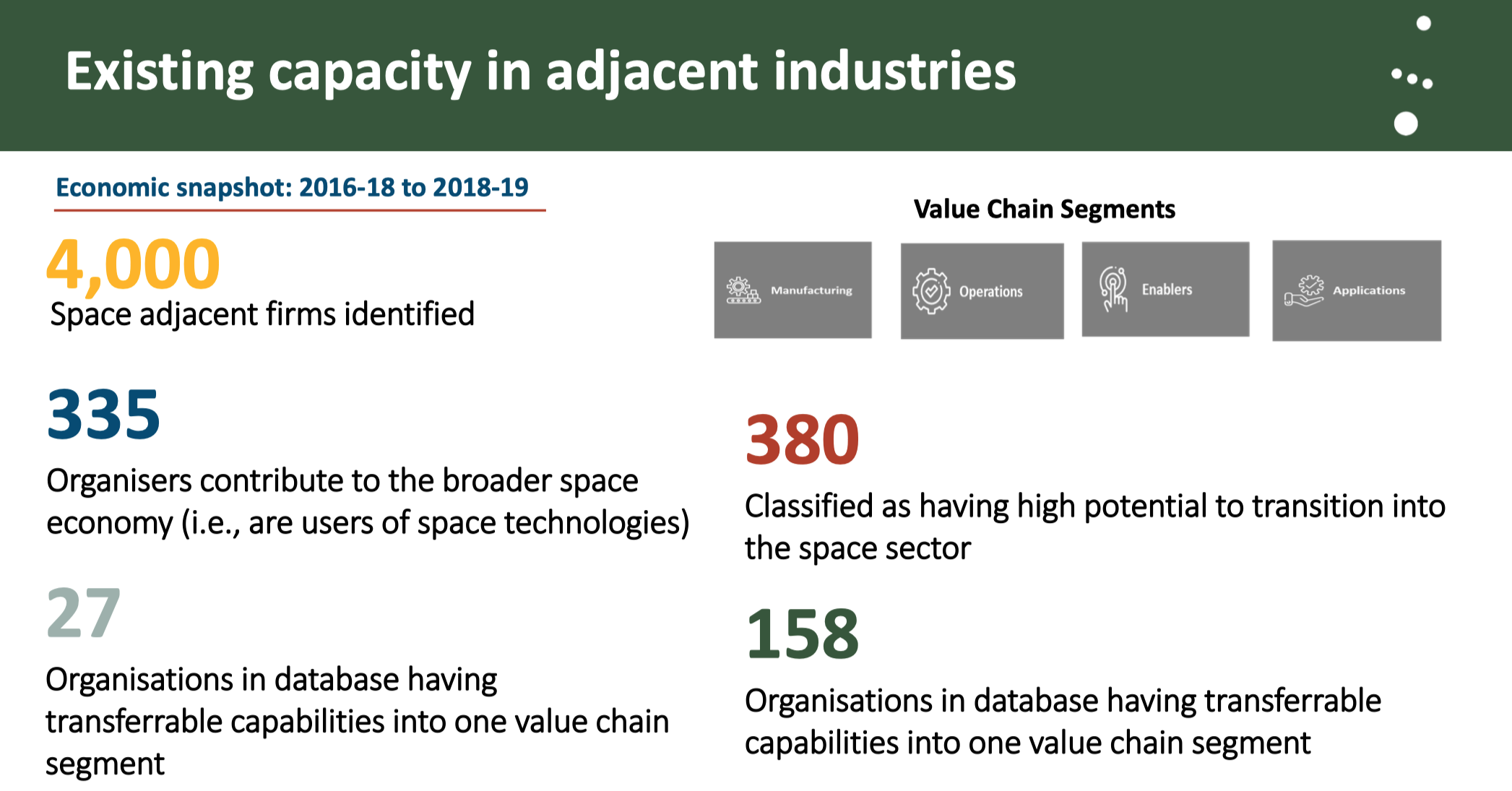

In the following slide from Murfett’s presentation, the extant capacity in adjacent industries within the Australian space industry eco system were identified:

He highlighted as well key infrastructure investments being made in Australia which can be leveraged as well to enhance the evolving Australian space industrial eco system. This includes the AU$1.3 billion in the modern manufacturing initiative of the Australian government, the establishment of a robotics, automation and AI command control centre (Fugro Marine), a space data analysis facility (Pawsey supercomputing Centre) and a missional control at Lot Fourteen (Saber Astronautics).

There is an agreement with NASA which is part of the way ahead for Australian space as well. The agreement with NASA means that Australia is part of the Trailblazer program of the Moon to Mars initiative. A semi-autonomous, Australian-made rover is to be included in future NASA mission to the Moon. This effort draws on Australia’s world-leading remote operations capability and the Rover will collect lunar regolith and NASA will extract oxygen from this.

Shaping a way ahead for Australian space launch capability is a key part of the way ahead. And in this slide from his presentation, Murfett highlighted the perceived way ahead:

A number of international agreements are being worked to open the doors internationally for the Australian space sector. The first is a technology safeguard agreement with the United States which is establishing principles under which U.S. spaceflight technology can be licensed for export to Australia for use in spaceflight activities. The Australians are working with India on India’s first human spaceflight program where the Australian Government and ISRO are working together to track the Gaganyaan mission from Australia’s Cocos (Keeling) Islands (CKI). And finally, there is an Australian-UK space bridge framework arrangement which Increases connection, exchange, and investment across AU-UK space sectors.

Murfett concluded his presentation by identifying what he saw as the next phase for the Australian civil space effort: Deliver the remaining technical roadmaps to highlight opportunities for investment; support industry to scale; connect across government to highlight how space can support growth, safety, and security; connect with the Australian community and show the value of space to our everyday lives and to inspire the nation and support the future workforce.

This last point was underscored in other presentations as well, for example, in the presentation by David Ball, regional director, Australia/New Zealand for Lockheed Martin Space.

“The young folks these days aren’t coming into space as we would need them to. In numbers, the Space Agency has some very aggressive numbers from government in terms of the numbers of jobs they need to create. To do that we need to inspire our younger generation and give them the path and show them there are real, tangible jobs in the space sector in this country.”

Murfett provided a fitting comment to highlight the way ahead for defence working with the evolving Australian space industrial eco system: “There is an Australian industry here that can actually deliver on Defence’s future ambitions.”

I would add that the challenge is to ensure that this happens in the way which fits as well into the evolution of the ADF, its forces, its strategy and its concepts of operations.

The featured phot is Anthony Murfett, Deputy Head of the Australian Space Agency speaking the Williams Foundation seminar on space.

[1] https://www.optus.com.au/about/network/satellite/fleet

[2] Commercial Space-Based Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance and Australia’s National Security (Geospatial Intelligence Pty Ltd (December 2021).