In a recent paper released by Malmgren-Glinsman Partners, the difficult situation in which the United States Government finds itself financially was underscored.

Their white paper argued: Over and above the concerns surrounding inflation and the economy, there are also daunting fiscal risks facing the U.S. government. And this situation will be aggravated by spending needed for new global commitments, the Ukraine War and spending for U.S, military operations.

They highlighted the factual situation as follows:

While financial market news is currently preoccupied with the inflation rate and possibility of recession, an entirely different policy challenge is emerging: How will mammoth U.S. Government debt be managed in the next 15 months before 2024 national elections?

The bipartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the federal budget deficit for the first 10 months of the current fiscal year (which runs from October 2022 to September 2023) is $1.7 trillion. This is more than twice the deficit for the same period in the preceding fiscal year.

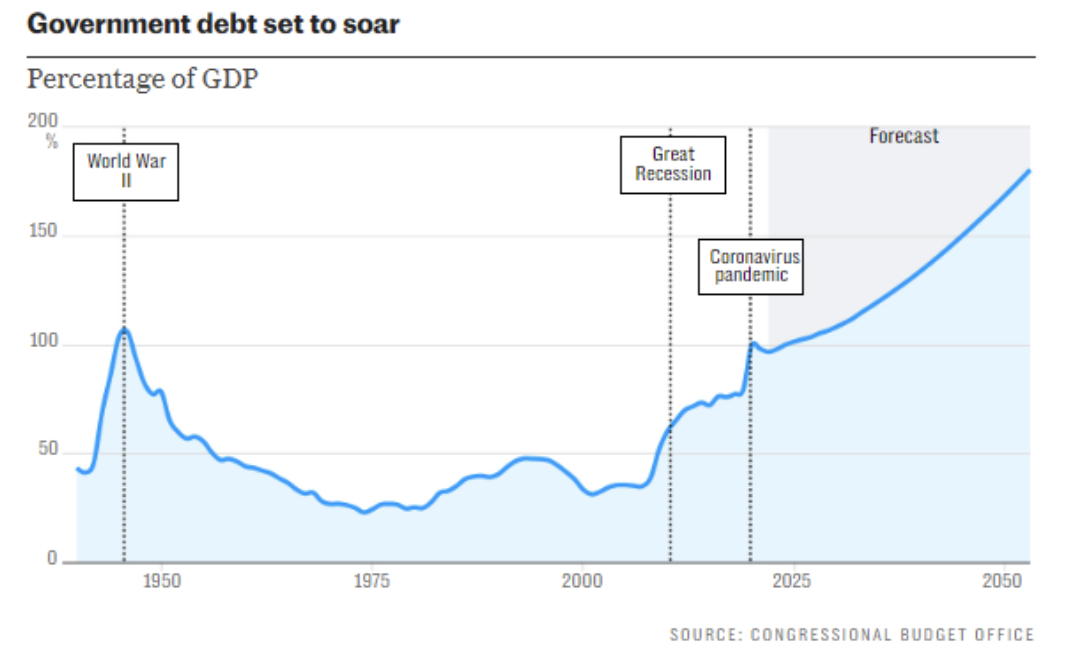

To put this escalating figure in perspective, government debt as a percent of GDP in the year 2000 stood below 50%, whereas U.S. government debt today stands at 118.6%, and is projected by the CBO to go even higher.

At the end of July, the U.S. Treasury announced that it expected to need to borrow $1,007 trillion from private markets in Q3 (July to September), and another $852 Billion in Q4 (October to December).

It was not made clear what assumptions had been made in these estimates.

It should be noted that the all-time high for quarterly borrowing of almost $3 trillion was hit in April-to-June 2020, thanks to the pandemic crisis.

In early August, several days after these numbers were announced, a Treasury spokesman said the Treasury was no longer assuming a recession in 2023. No recession is a growing financial market view. No recession would mean no large decline in tax receipts or rise in counter-cyclical spending such as unemployment compensation.

However, tax receipts have slowly been declining in recent weeks, suggesting sagging economic activity.

Falling measures of physical economic activity, such as declining volume of shipments of goods by sea, rail and trucks, are suggesting significant slowdown.

If, as we expect, recession begins to erode GDP growth, then the July 31 borrowing estimates would have to be revised to take into account rising unemployment benefit expenditures and falling tax receipts, resulting in larger numbers for the remainder of this year, and of course, higher numbers well into 2024.

They then reviewed the global situation and how the Administration is spending defense money, notably in Ukraine, and argued that the global situation will likely accelerate the debt problem.

They highlighted the various commitments the Biden Administration is making globally which require increased defense spending and then underscored that the Ukraine aid added to these commitments and increased spending necessary for operations short of the beginning of armed conflict with a peer competitor. These actions all argue for increased defense spending ON TOP of the current debt structure.

They noted:

Enhanced integration of U.S. military responses with Japan, Australia, South Korea, and possibly other like-minded nations is being actively pursued.

As part of U.S. military conflict contingency planning, the U.S. military is likely considering wider dispersion of its military presence in other locations in the neighborhood of the South China Sea, Sea of Japan and the Pacific Island rings.

If an armed conflict between the U.S and China were to happen, there is no doubt that management of the U.S. government budget would be dramatically affected. Wars are brutally expensive. Moreover, the costs of conducting an armed conflict are invariably underestimated when political decision makers decide to act without elaborate analysis by the military in advance.

How viable is such a situation?

And where is the strategy to deal with it?

If the U.S. did find itself entangled in an armed conflict, the U.S. Treasury would have to develop an emergency debt management program that would entail massive new borrowing.

This possibility has been given virtually no thought in Congress or mainstream journalism.

Even if no armed conflict took place, a process of preparing for conflict would inevitably entail dramatic escalation of the defense budget to cover widespread deployment of U.S. forces throughout the Indo-Pacific Command.

A new National Defense Activity Authorization would have to be enacted.

With that, new Treasury operations scenarios would have to be developed, and the Federal Reserve would have to reconsider the changed financial market parameters posed thereby.