By Robbin Laird

The era of autonomous maritime operations has quietly arrived, moving beyond experimental trials to become operational reality.

A recent conversation with Robert Dane, CEO of OCIUS, underscores how autonomous vessels are fundamentally changing naval operations—and why traditional naval thinking must evolve to harness their potential.

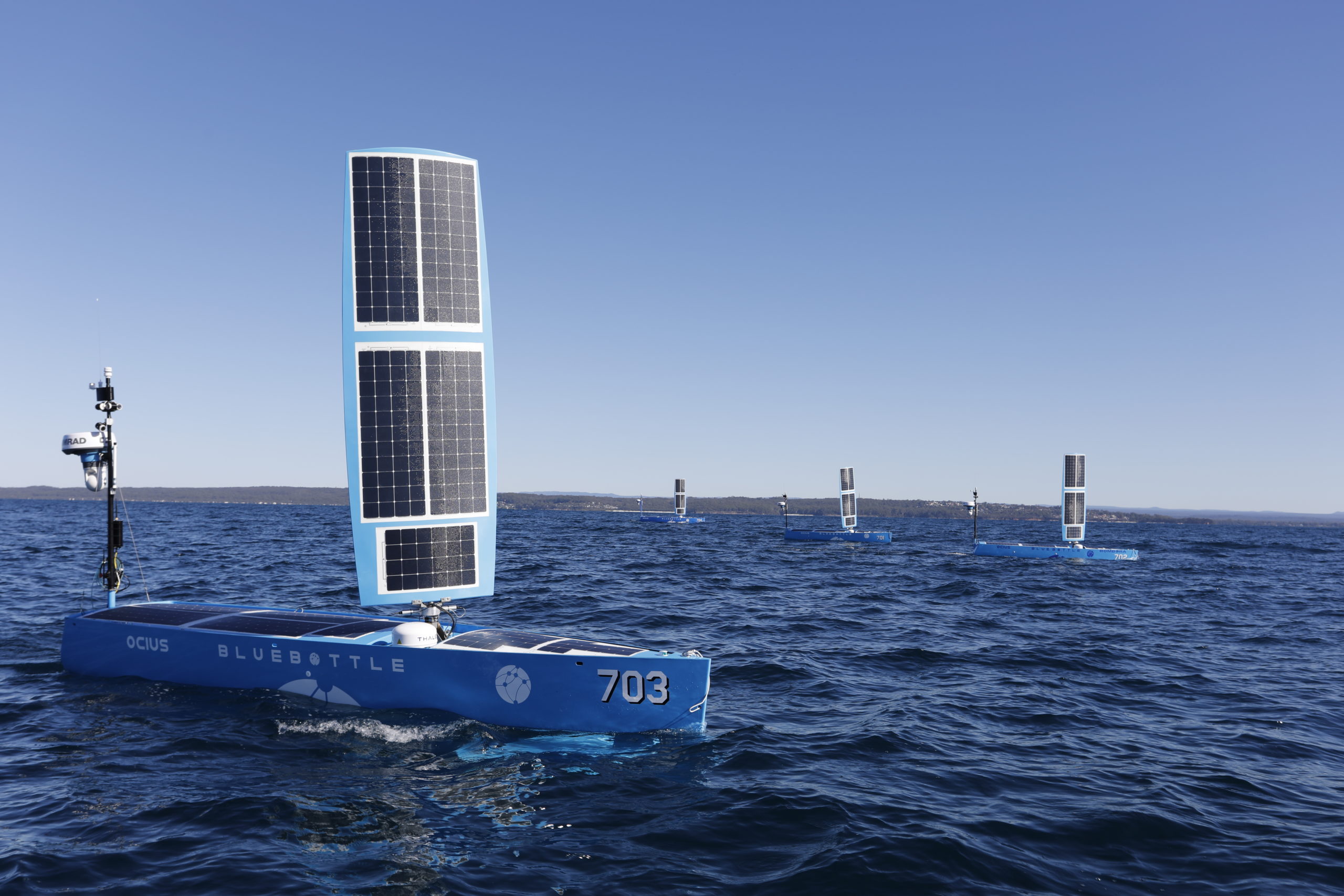

OCIUS’s journey from startup to operational service provider illustrates the broader transformation occurring in maritime defense. The company currently operates 12 autonomous vessels continuously from Darwin, with deployments averaging 60 days and reaching as long as 107 days.

This isn’t experimental anymore — it’s sustained operational capability.

The operational tempo speaks for itself: OCIUS has maintained 24/7 operations since July 2024, supporting anti-submarine warfare demonstrations and providing persistent surveillance across vast ocean areas. Three additional vessels equipped with radar systems are planned for deployment, while international programs in Japan and the UK are following Australia’s lead.

This reminds of my experience with the Osprey as it gained acceptance in what was an uphill battle.

In a 2012 interview I conducted at Marine Corps air station New River with LtCol Brian McAvoy, the Commanding officer of VMM-264, he underscored the progress they were having this way: “In 2006, it felt like we were a bar act. It was challenging to get there and we were seen as oddities. In 2012, we were flying a plane with years of combat experience. We no longer were a bar act, but war fighters flying and maintaining a key combat capability.”

Central to this transformation is what I have called a mesh fleet in my new book focused on the paradigm shift in paradigm operations—a distributed network of autonomous vessels working collaboratively rather than relying on expensive capital ships. This represents a fundamental departure from traditional naval thinking.

The goal is to get them to work together for whatever task you’ve got to deploy in terms of a payload. It’s task orientation we’re talking about. You’re putting a payload on your USV to do a specific task.

This approach offers several advantages over traditional naval operations:

- Distributed Risk: Instead of risking a billion-dollar vessel with hundreds of crew members, naval forces can deploy multiple smaller autonomous assets. If one malfunctions, the mission continues with the remaining fleet.

- Personnel Efficiency: A mesh fleet requires only a handful of operators for monitoring and control, compared to the personnel required for traditional naval vessels.

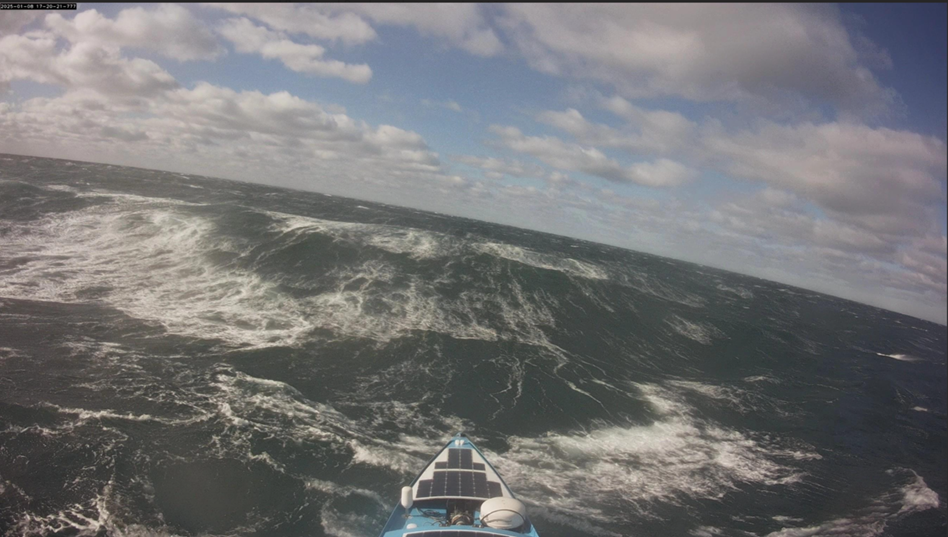

- Operational Flexibility: Autonomous vessels can be deployed for extended periods without the human factors that limit traditional operations—no crew fatigue, no need for food supplies, and no requirement for crew rotation.

Perhaps the most compelling argument for autonomous maritime systems lies in their economic impact. Traditional cost analyses fail to capture the true expense of manned operations.

Dane underscored: “If you look at an all-manned operation versus partial autonomous operations, the cost includes salary, medical, retirement—these factors add up to a significant bill to be paid by naval forces. When patrol boats cost significant amounts of dollars per day on station but operate limited schedules due to crew requirements, the true cost per operational day becomes substantially higher.”

Autonomous systems eliminate many of these hidden costs. There are no retirement benefits for a Blue Bottle vessel, no medical expenses, and no requirement for extensive shore-based support infrastructure. The maintenance burden shifts from large crews to small technical teams, and vessels can operate continuously rather than following traditional deployment cycles.

Despite operational success, autonomous maritime systems face institutional resistance rooted in traditional naval culture. The challenge extends beyond individual attitudes to procurement philosophy. Current Australian plans to develop large unmanned surface vessels armed with missiles misses the strategic advantage of distributed, flexible systems that can mask capabilities and confuse adversaries about fleet composition and intentions.

Maritime autonomous systems enable entirely new operational concepts. Traditional naval forces must choose between expensive, multi-mission platforms or accepting capability gaps. Autonomous systems offer a third option: task-specific deployment of distributed assets.

This shift requires new command structures and operational thinking.

The information warfare implications are particularly significant. Admiral Paparo’s concept of information warfare as “the first battle” aligns perfectly with autonomous systems’ persistent surveillance capabilities. These platforms excel at providing continuous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance without the human factors that limit traditional operations.

OCIUS’s flexible business model addresses another challenge: how naval forces can adopt autonomous systems without developing entirely new maintenance and operational capabilities. The company offers everything from complete end-to-end operations to mission-area handover, allowing navies to focus on their core competencies while leveraging commercial expertise for platform management.

The global nature of autonomous maritime development creates both opportunities and challenges. Japan’s keen interest in Australia’s autonomous operations reflects similar strategic challenges, while UK programs demonstrate parallel development paths.

The company’s evolution from experimental developer to operational service provider represents a template for the broader industry.

Autonomous maritime systems succeed not by replacing traditional naval capabilities but by enabling new operational concepts that were previously impossible or prohibitively expensive.

The question isn’t whether autonomous systems will transform naval operations — that transformation is already underway. The question is whether naval institutions will adapt quickly enough to harness their potential, or whether they’ll be constrained by capital ship thinking in an era that demands distributed, flexible operations.

For naval forces facing personnel shortages, budget constraints, and expanding operational requirements, autonomous systems offer a path forward. But realizing their potential requires more than technological adoption—it demands fundamental rethinking of naval strategy, operations, and economics.

The maritime revolution has begun. The challenge now is ensuring that institutional adaptation keeps pace with technological capability.

The photos in the slide show below were provided by OCIUS.

On the Amazon U.S. site:

On the Amazon Australian site: