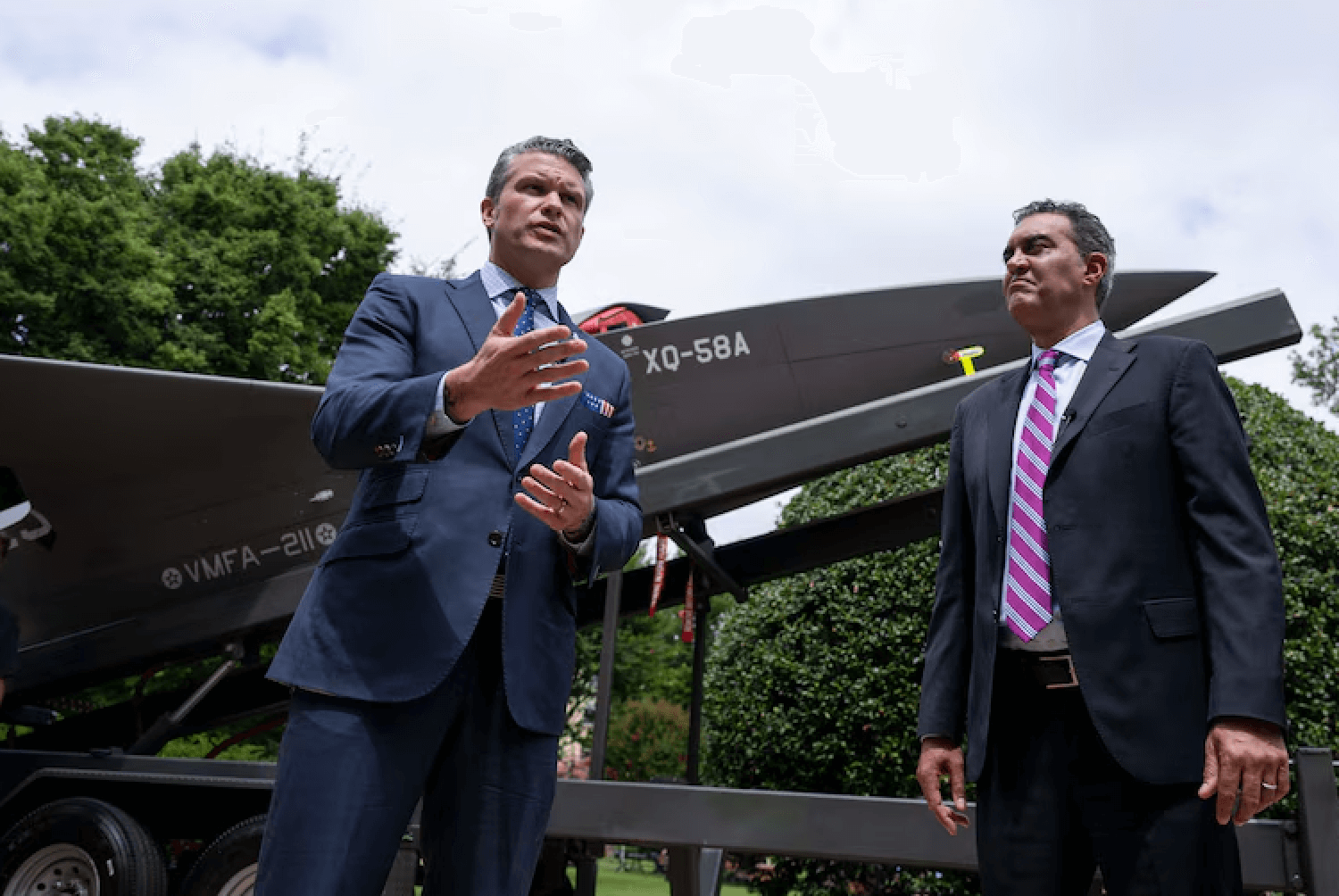

In July 2025, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth unveiled a new Pentagon drone policy, formally entitled “Unleashing U.S. Military Drone Dominance.”

The idea is to have a sweeping overhaul designed to accelerate the acquisition, deployment, and use of small drones across the entire U.S. military.

The policy shift comes at a critical juncture as global military drone production has skyrocketed, with adversaries collectively producing millions of cheap drones annually while the U.S. has struggled with bureaucratic red tape.

As Hegseth noted in his announcement, “Drones are the biggest battlefield innovation in a generation, accounting for most of this year’s casualties in Ukraine.”

A key element of the policy is the reclassification of small drones as “consumables” rather than durable property. Group 1 and Group 2 unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) — those weighing under 55 pounds — will now be “accounted for as consumable commodities, not durable property,” according to the policy documents.

This shift acknowledges a battlefield reality that has emerged from conflicts like the war in Ukraine: drones are expected to be used up and lost in combat, much like ammunition or grenades. “Small UAS resemble munitions more than high-end airplanes. They should be cheap, rapidly replaceable, and categorized as consumable,” the Pentagon’s guidance states.

The Pentagon defines Group 1 drones as systems weighing up to 20 pounds that can fly up to 1,200 feet altitude and reach speeds of 100 knots. Group 2 includes drones between 21 and 55 pounds, capable of reaching 3,500 feet altitude and speeds up to 250 knots.

The new policy dramatically expands who can buy, test, and deploy drones within the military hierarchy. For the first time, commanders at the colonel and Navy captain level can independently procure and test drones, including 3D-printed prototypes and commercial off-the-shelf systems, as long as they meet national security criteria.

This represents a significant departure from previous procurement processes that required multiple layers of approval and could take months or years to complete. The policy also enables troops to modify drones in the field as necessary for specific operational needs, fostering innovation at the tactical level.

This makes a great deal of sense as the development of the software and AI systems guiding the drones has to constantly be adapted to changing battlefield realities. These are not platforms to be acquired as platforms; but embodied AI and software systems which morph over time in their platforms and require the code writers and the users to be symbiotically connected.

The Pentagon has established ambitious deadlines that underscore the urgency of this transformation:

By September 1, 2025: All military branches must establish specialized experimental drone units designed to rapidly scale small drone use across the joint force. By end of fiscal year 2026: Every Army squad must be equipped with small, “one-way” attack drones (expendable kamikaze drones), with Indo-Pacific units receiving priority.

By September 2026: The Pentagon aims to have procured and fielded thousands of drones, with some Army programs already seeking to purchase 10,000+ units for less than $2,000 each.

The policy also mandates that by 2027, all major training events across the Department of Defense must integrate drone capabilities, fundamentally changing how the military trains for modern warfare.¹¹

One of the most significant barriers to rapid drone deployment has been the lengthy certification process.

The new policy addresses this with strict deadlines: certification requests must receive answers within 14 days, compared to months under the previous system. Weapons approvals for small drones will take just 30 days instead of the previous 90-120 days.

The long-criticized “Blue sUAS” approval system is being comprehensively reformed. The program, which maintains a list of Pentagon-approved drones, is being transferred from the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) to the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) by January 1, 2026, with significantly expanded resources and staffing.

The Pentagon is taking unprecedented steps to support American drone manufacturers and expand the industrial base. Within 30 days of the policy announcement, the Office of Strategic Capital and Department of Government Efficiency were tasked with proposing financing options including advance purchase commitments, direct loans, and other capital incentives to help domestic drone companies scale up quickly.

The policy specifically states that major purchases “shall favor U.S. companies,” signaling a clear preference for domestic production capability. Third-party testing is now permitted, allowing multiple assessors to certify products rather than relying solely on government testing, which should dramatically reduce bottlenecks.

Hegseth’s directive rescinds several restrictive policies that had hindered drone procurement, including a 2022 memo about requirements for Blue sUAS systems and a 2021 memo outlining operational procedures that implemented congressional restrictions on drones from certain foreign entities.

“I am rescinding restrictive policies that hindered production and limited access to these vital technologies, unleashing the combined potential of American manufacturing and warfighter ingenuity,” Hegseth wrote in the policy memo.

The urgency behind these changes becomes clear when examining global production capacity. China has developed the ability to produce approximately 100,000 small drones monthly, while the U.S. defense industrial base currently produces only 5,000 to 6,000 small drones monthly.

This production gap has significant implications for any potential large-scale conflict, where drone consumption rates could be enormous. The war in Ukraine has provided a preview of this reality, with both sides consuming drones at unprecedented rates.

The Pentagon’s fiscal year 2026 budget request reflects this new strategic priority, with $13.6 billion allocated for autonomous military systems, including $9.4 billion specifically for unmanned and remotely piloted vehicles. This represents the largest research and development investment in drone technology in Pentagon history.

Additional funding includes $210 million for autonomous land vehicles, $1.7 billion for Army sea drones, $1.1 billion for Army reconnaissance drones, and $1.2 billion for software development across all military services’ drone programs.

The policy builds on a June 2025 White House executive order titled “Unleashing American Drone Dominance,” which focused on civilian drone operations and commercial integration. The Pentagon’s approach aims to leverage civilian innovations, including artificial intelligence and commercial drone technologies, to leapfrog current military capabilities.

The military will develop a “dynamic, AI-searchable Blue List”—a digital platform cataloging approved drone components, vendors, and performance ratings. By 2026, this system will be operated by DCMA and powered by nightly AI retraining pipelines.

The policy mandates a complete transformation of military training. By next year, Hegseth expects to see drone capabilities integrated into “all relevant combat training, including force-on-force drone wars.” Military departments must establish at least three national drone training ranges with diverse terrain, including over-water areas, within 90 days of the policy announcement.

This policy shift creates opportunities for American drone manufacturers while fundamentally changing the strategic calculus for military operations. The emphasis on mass production of low-cost, expendable systems mirrors lessons learned from the Ukraine conflict, where cheap, numerous drones have proven more effective than smaller numbers of expensive platforms.

The policy also reflects a broader recognition that future conflicts will likely be decided not just by technological superiority, but by the ability to produce and deploy military systems at scale and speed. By treating drones as consumables and dramatically streamlining procurement, the Pentagon is positioning itself for a new era of warfare where quantity, speed of deployment, and rapid replacement capabilities may be as important as individual platform sophistication.

As Defense Secretary Hegseth concluded in his announcement, “Lethality will not be hindered by self-imposed restrictions, especially when it comes to harnessing technologies we invented but were slow to pursue. Drone technology is advancing so rapidly, our major risk is risk-avoidance. The Department’s bureaucratic gloves are coming off.”

All of this can lead to effective change for the “fight tonight” force but only if it is worked with evolving C2, EW and ISR capabilities. Drones are NOT a substitute for how to work a kill web — they are simply paylloads.

A danger is always the new bit of warfare suggesting that warfare is transformed only by incorporating that new kit.

It isn’t.

Being able to integrate effective ISR and C2 in working combat clusters using manned and unmanned systems effectively is the challenge. Drones do not solve that problem but they can provide tools to do so.

Finding ways to integrate the payloads of the evolving force into an effective and lethal and focused force is the challenge.

When looking at the Ukrainian conflict, one can be mesmerized by drones and forgetting the years of training with Western militaries and the significant Western kit they operate with. It is a hybrid or blended force we are looking, one which can incorporate drones rather than being enamored of them.

Also, the platform element can be very critical when working a deployed force to assist the manned force. Not all platforms are alike — some are truly like bullets, others are more like effective carriers of payloads which you want to resuse and load with divergent payload packages. This is espeicallly true when understanding that the “fight tonight” force needs to be sustainable, and flooding such a force with many disposable drones may be a path to reducing significantly the combat effectivenss of a force.

The Hegseth action is a significant opening on change; but it is just that — only an opening.

How Ukraine Transformed Western Military Aid and Domestic Innovation into a Dynamic Defense Model

A Paradigm Shift in Maritime Operations: Autonomous Systems and Their Impact