By Robbin Laird

The reactivation of Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 264 (VMM-264) represents far more than a simple administrative redesignation or force structure adjustment. It signals the Marine Corps’ recognition that its transformation under Force Design 2030 requires expanded, not contracted, capabilities in certain critical areas, particularly in the aviation domain that enables distributed maritime operations across the vast Indo-Pacific theater.

VMM-264’s return comes at a pivotal moment when the Marine Corps is simultaneously divesting legacy capabilities while investing in new technologies and operational concepts. The squadron’s reactivation reflects hard-earned lessons from recent operational experience: that the MV-22 Osprey remains indispensable to Marine Corps expeditionary operations, and that the service needs additional capacity to execute its evolving mission set in an era of great power competition.

Historical Context: The Black Knights’ Legacy

VMM-264, known as the “Black Knights,” carries a distinguished lineage dating back to its original activation as a CH-46 Sea Knight squadron. Like many Marine Corps aviation units, the squadron transitioned through multiple aircraft types and designations, reflecting the service’s continuous adaptation to changing operational requirements. The unit’s deactivation was part of broader force structure reductions following the drawdown from counterterrorism operations, when the Marine Corps began reassessing its future force composition.

The decision to reactivate VMM-264 specifically, rather than simply increase manning at existing squadrons, carries symbolic and practical significance. Symbolically, it reconnects the service to its operational heritage and the combat experience embedded in unit histories. Practically, it provides organizational structure for rebuilding tiltrotor capacity without overextending existing squadrons already strained by high operational tempo and modernization pressures.

The Osprey’s Enduring Relevance

The MV-22 Osprey has proven itself as a transformational platform for Marine Corps operations, despite persistent safety concerns and mechanical challenges that have garnered public attention. Its unique combination of helicopter-like vertical lift and turboprop speed and range creates capabilities no other platform can match, making it essential for the distributed operations concepts central to Force Design 2030.

In my extensive field research with the Second Marine Aircraft Wing, I’ve observed how the Osprey fundamentally changed Marine Corps operational thinking. The aircraft’s 275-knot cruise speed and 1,100-nautical-mile range enable rapid force deployment across distances that would require multiple helicopter refuelings or fixed-wing aircraft with different basing requirements. This capability becomes critical in Indo-Pacific geography, where vast ocean expanses separate potential operating areas and adversary anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) systems threaten traditional basing infrastructure.

The Osprey’s role extends beyond simple transportation. In distributed maritime operations and Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), MV-22s serve as connective tissue linking dispersed Marine Littoral Regiments, expeditionary advanced bases, and naval platforms. They provide the rapid repositioning capability essential to the “inside forces” concept or what I prefer, the impact force concept. I will explore this concept in future articles.

Moreover, the Osprey fleet has evolved significantly since initial operational capability. Upgraded defensive systems, improved reliability, enhanced maintainability, and integration with fifth-generation aircraft like the F-35B have made modern MV-22s far more capable than early production models. The aircraft has become increasingly networked, able to operate within the distributed kill webs that characterize contemporary Marine Corps operational concepts rather than the linear kill chains of previous decades.

The recent Steel Knight 2025 exercise which I observed in the month of December with 3rd Marine Air Wing was based around the kill web concept and the role of the Ospreys were a key backbone to executing this approach.

Force Design 2030 and Aviation Requirements

General David Berger’s Force Design 2030 initiative fundamentally restructured the Marine Corps for competition and conflict with peer adversaries, particularly China in the Indo-Pacific. The initiative’s divesting of legacy capabilities. including all tank battalions, much of the tube artillery, and reduction in traditional infantry units, proved controversial but reflected clear strategic choices about future operating environments.

However, Force Design 2030 never envisioned reducing aviation capacity across the board. Instead, it emphasized quality improvements and capability modernization while recognizing that certain platforms remain essential. The F-35B/C fleet expansion continues as the centerpiece of Marine Corps tactical aviation modernization. The CH-53K King Stallion provides heavy-lift capacity that no other platform can match, essential for moving the heavy equipment that remains in the lighter Marine Corps force structure. And the MV-22 provides the medium-lift and rapid-deployment capabilities that enable distributed operations.

VMM-264’s reactivation suggests the Marine Corps has concluded that its Osprey fleet needs expansion, not just sustainment at current levels. This conclusion likely stems from several operational realities that became apparent during Force Design implementation.

- First, the Indo-Pacific’s geography demands more aircraft to cover required distances and maintain operational tempo.

- Second, distributed operations concepts require more platforms to simultaneously support multiple dispersed elements.

- Third, maintaining forward presence while conducting necessary training, maintenance, and modernization activities requires greater capacity than initially projected.

The reactivation also reflects what I’ve termed the shift from crisis management to chaos management in modern military operations. Traditional crisis management assumes a stable baseline to which operations return after addressing specific challenges. Chaos management recognizes that contemporary operating environments are persistently complex, requiring forces to operate effectively within ongoing turbulence rather than seeking to restore stability. This approach demands greater organizational resilience and capacity, including more squadrons that can absorb operational tempo fluctuations without degrading readiness.

Operational Implications

VMM-264’s return to active status creates several immediate operational opportunities. An additional squadron provides Second Marine Aircraft Wing with greater flexibility in supporting Marine Littoral Regiment operations, which form the core of the inside forces concept. It enables more robust support for distributed maritime operations exercises across the Indo-Pacific, where Marines increasingly train alongside allied and partner forces to develop interoperable capabilities.

The new squadron also helps address the persistent challenge of balancing deployment requirements against training and modernization needs. Marine Corps aviation has struggled with this balance for years, as high operational tempo reduces time available for individual skill development, collective training at higher echelons, and integration of new systems and tactics. An additional VMM provides breathing room across the enterprise, allowing other squadrons to dedicate more time to these essential activities without creating deployment gaps.

From a strategic perspective, VMM-264’s reactivation signals to allies and adversaries alike that the Marine Corps is expanding rather than contracting its expeditionary aviation capabilities. This matters particularly in the Indo-Pacific, where regional partners monitor U.S. force posture signals as indicators of commitment. An expanding tiltrotor fleet demonstrates that American expeditionary forces can operate across the region’s vast distances, reinforcing deterrence by demonstrating capability and resolve.

Integration with Broader Aviation Transformation

The squadron’s reactivation occurs within a broader Marine Corps aviation transformation that I’ve documented extensively through field research. This transformation includes several interconnected elements that create a more capable overall force.

The F-35B/C integration represents the most significant tactical aviation advancement in Marine Corps history. These fifth-generation aircraft provide unprecedented situational awareness, sensor fusion, and network integration that fundamentally changes air combat dynamics. However, their effectiveness depends on supporting infrastructure, including the MV-22s that deploy maintenance personnel, spare parts, and command elements to austere locations where F-35s might operate during distributed campaigns.

The CH-53K King Stallion modernization provides heavy-lift capacity triple that of legacy CH-53E Super Stallions, enabling movement of bulky equipment like Joint Light Tactical Vehicles, generators, and command posts essential to expeditionary advanced bases. But heavy-lift alone cannot meet all operational requirements, medium-lift tiltrotors remain essential for rapid personnel movement, time-sensitive resupply, and operational maneuver at tempos that exploit fleeting windows of opportunity.

Unmanned systems proliferation creates additional complexity and opportunity. The Marine Corps is fielding various unmanned aerial systems for reconnaissance, logistics, and potentially strike missions. These systems don’t replace manned aviation but complement it, creating more diverse force packages that complicate adversary targeting and planning. Managing this increasingly complex aviation ecosystem requires adequate capacity across all platform types, including the tiltrotor fleet that connects dispersed elements.

Training and Development Challenges

Reactivating VMM-264 presents significant training and personnel development challenges that extend beyond simply assigning aircraft and personnel to a new organizational structure. The Marine Corps must generate sufficient MV-22 aviators, crew chiefs, maintainers, and support personnel while existing squadrons already face manning pressures.

The tiltrotor training pipeline has evolved considerably since the Osprey’s initial fielding. Modern pilot training increasingly emphasizes cognitive skills over traditional stick-and-rudder proficiency, recognizing that contemporary aviation demands decision-making within complex, networked environments. This shift parallels developments I’ve observed in advanced flight training programs like Italy’s International Flight Training School, where Live-Virtual-Constructive training systems prepare pilots for fifth-generation operations by emphasizing tactical decision-making and situational awareness.

For VMM-264 specifically, establishing an effective training program requires balancing immediate operational requirements against long-term capability development. The squadron cannot simply focus on basic MV-22 operations. It must integrate into the broader MAW operational framework, develop proficiency in distributed operations concepts, and build interoperability with joint and allied forces. This demands time and resources that competing priorities may challenge.

The maintenance and sustainment challenges are equally significant. The Osprey remains a complex aircraft with demanding maintenance requirements. Establishing VMM-264’s maintenance capabilities requires not just assigning maintainers but developing unit-level expertise in troubleshooting, parts management, and coordination with depot-level maintenance activities. This organizational knowledge takes time to build and represents a long-term investment in squadron capability.

Strategic Signaling and Deterrence

Beyond immediate operational benefits, VMM-264’s reactivation contributes to strategic deterrence in ways that transcend the squadron’s tactical capabilities. In great power competition, force structure decisions signal intentions, priorities, and resolve to both adversaries and allies. Expanding tiltrotor capacity demonstrates American commitment to maintaining expeditionary capabilities that enable distributed operations across contested spaces.

China carefully monitors U.S. military developments, seeking indicators of American commitment to Indo-Pacific security. A Marine Corps that expands rather than contracts its expeditionary aviation sends clear messages about American intentions to maintain forward presence and operational capacity throughout the region. This matters because deterrence depends not just on possessing capabilities but on demonstrating willingness to employ them and maintaining sufficient capacity to do so sustainably.

For allies and partners, VMM-264’s return reinforces confidence in American security commitments. Regional partners from Japan to Australia to the Philippines closely watch U.S. force posture decisions, understanding that American capabilities directly affect regional security dynamics. An expanding Marine Corps tiltrotor fleet enhances prospects for combined operations, security cooperation activities, and crisis response—all essential elements of the network of relationships that underpin Indo-Pacific stability.

Looking Forward

VMM-264’s reactivation represents an important chapter in the ongoing narrative of Marine Corps transformation, but it raises questions about future force structure decisions.

- Does this signal broader aviation expansion beyond a single squadron? How will the Marine Corps balance tiltrotor capacity against other competing modernization priorities?

- What does this mean for the overall trajectory of Force Design 2030 as initial implementation yields to operational experience?

The answers will emerge through continued experimentation, exercises, and operational deployments that test emerging concepts against real-world challenges. What seems clear is that the Marine Corps has concluded its tiltrotor fleet requires expansion to meet operational demands in the Indo-Pacific and other priority theaters. This represents a course correction based on operational reality, precisely the kind of adaptive learning that successful military transformation requires.

As General Patton observed, “if everyone is thinking alike, someone isn’t thinking.” VMM-264’s reactivation suggests Marine Corps leadership is thinking critically about aviation requirements rather than simply following predetermined trajectories. This willingness to adjust based on operational experience, even when it means reversing previous force structure decisions, demonstrates the intellectual flexibility essential to navigating strategic competition’s inherent uncertainties.

The Black Knights’ return marks not an ending but a beginning of renewed capability, expanded capacity, and continued adaptation to the challenges of operating in an era where chaos management rather than crisis management defines success.

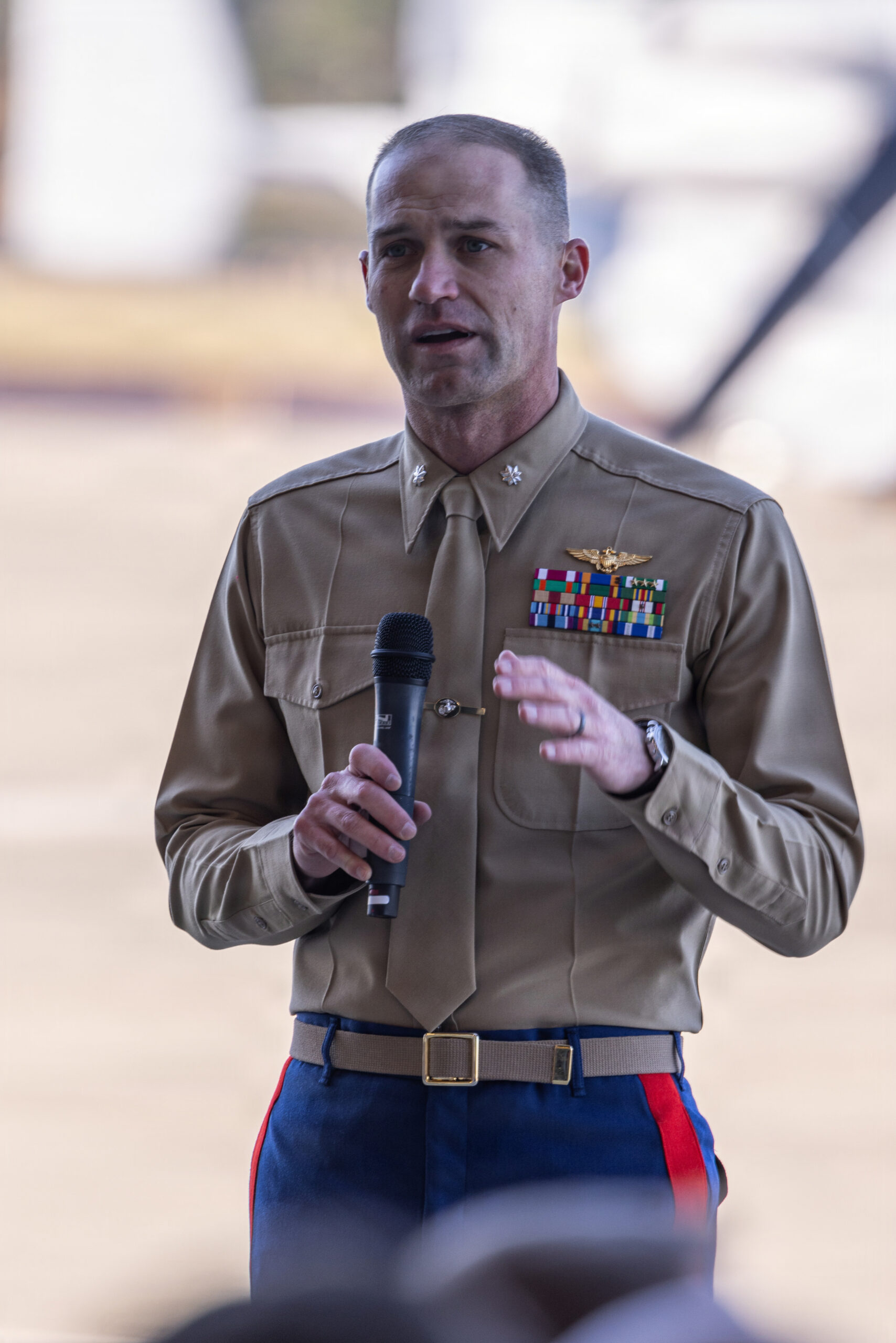

Note: VMM-264 as seen in 2011: