2016-02-12 By Scott Truver

In the early morning of Feb. 18, 1991, the U.S. amphibious warship USS Tripoli (LPH-10) struck an Iraqi contact mine in the northern Persian Gulf, ripping a 25-foot by 23-foot hole in her starboard side below the waterline.

The quick reaction of her commanding officer and his crew managed to keep the ship on an even keel. That allowed Tripoli—which, ironically, was serving as a mine countermeasures (MCM) support ship with embarked airborne MCM helicopters—to continue mine-clearance operations for another six days before heading to port for repairs.

Compare that experience to that of the Sri Lankan navy’s logistics ship M/V Invincible which was attacked by the Tamil Sea Tigers on 9 May 2008. Built as a commercial vessel but transferred to the navy, the 210-foot Invincible was loaded with ammunition and explosives intended for government troops.

A simple limpet mine planted by a Sea Tiger diver sank the ship. A cheap kill if ever there was one.

One blindingly obvious lesson from real-world combat events is that surface ships built to military standards are more likely to survive attacks than are vessels designed to commercial standards.

Indeed, numerous critical factors in the Navy’s Survivability Instruction 9070.1A are taken into account in designing U.S. Navy surface ships to three survivability standards:

Level 1 (low);

Level 2 (moderate);

and Level 3 (high).

Aircraft carriers, cruisers and destroyers are designed to Level 3.

Amphibious warships and some underway replenishment ships are designed to Level 2.

Both versions of the littoral combat ship (LCS), other replenishment ships, mine warfare ships, patrol craft, and support ships are designed to Level 1.

Then there are Navy vessels that are built to commercial standards.

The damage, injuries and deaths resulting from the 17 October 2002 terrorist attack on the Aegis guided-missile destroyer USS Cole (DDG-67) could have been much worse had the ship not been designed to Level 3 standards and without the excellent damage-control capabilities of her well-trained crew.

Tripoli was rated at Level 2, while the Sri Lanken Invincible, despite her name, was built to commercial “Level 0” survivability, with damage control little more than a prayer.

Why dredge up this history?

Lessons learned in combat must remain in focus as the Navy and the Marine Corps are challenged to carry out today’s operations with reduced forces while simultaneously planning and programming for an uncertain but still-dangerous future.

Nowhere is this more challenging than assuring the sea services’ expeditionary-from-the-sea capabilities.

During the past decade or so, as defense budgets were squeezed and amphibious force structure was stretched thin to meet combatant commanders’ near-insatiable demands for more ships, the Navy and Marine Corps reached for innovative alternative platforms to enable more littoral operations, particularly in lower-threat regions of the world.

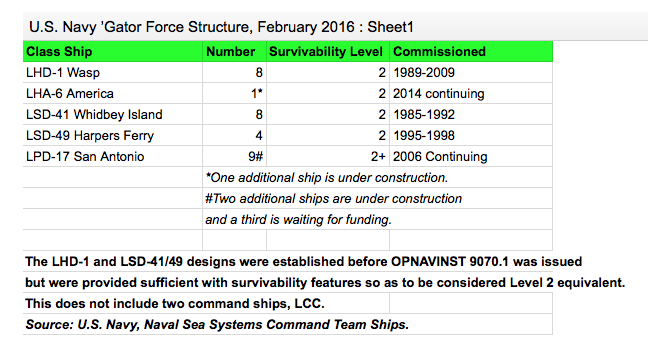

That was largely due to the fiscal reality that the long-established requirement for 38 amphibious ships––an “alphabet soup” of LHDs, LHAs, LPDs and LSDs––would likely never be achieved, and at most a force of 33 Gators would be sustained.

“There is a requirement for over 50 [amphibious] ships on a day-to-day basis, that’s what . . . the combatant commanders are asking for,” Gen. Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., then-Marine Corps Commandant, noted at the January 2015 WEST conference in San Diego.

“We’ve got an objective of 38—that’s the requirement within the Department of the Navy. We’ve got a fiscally constrained objective of about 33. We’ve got an inventory right now of 31 . . . which equates to significant readiness challenges.”

A 33-ship force would include 15 amphibious ships for each MEB [Marine Expeditionary Brigade], with another three ships in overhaul at any given time.”

Since then, the Navy’s shipbuilding plan has been bumped up by one amphib, but numerous Cassandras are less optimistic and point to a more likely, budget-constrained 28-ship future amphibious force.

Go below even 34 and important factors––e.g., material readiness––start to reduce force effectiveness.

During a hearing before the Seapower and Projection Forces subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee on Feb. 23, 2015, Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Kenneth J. Glueck Jr., deputy commandant for Combat Development and Integration and the commanding general of the Marine Corps Combat Development Command, stated that the number needed to satisfy COCOM demands for forward-deployed amphibious ships is “close to 54.”

This situation has stimulated new thinking about traditional as well as novel approaches to sustain the nation’s ability to project expeditionary power from the sea.

But these are always predicated upon the sustained core capabilities and minimum essential numbers of the nation’s ’Gators.

As Daniel Goure of the Lexington Institute concluded in October 2015, “The unraveling of the post-World War II international order fairly cries out for a larger and modern U.S. amphibious warfare capability.”

An over-reliance on designed-to-commercial-standards vessels to compensate for a severely numbers-constrained amphibious force runs the risk of easy mission-kills if not catastrophic losses of ships and crews.

That’s not to say these “ancillaries,” as former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert described them, would be of no value.

To the contrary, they offer critical services and capabilities during peacetime and crisis, providing persistent presence in many areas of the world, thereby allowing gray-hulled amphibs to be deployed to regions of greater danger.

As Maj. Gen. Richard Simcock, commanding general, 3d Marine Division, remarked in a January 2016 USNI News interview, “what we’re finding out now is, we have to use these resources outside their original design. We cannot afford to just let them sit and not be used. We are finding ways of using these ships to support the engagement that we’re doing throughout the region.”

In that regard, three ship types have been highlighted as a means to assuage the risk in the arrival of combat support and combat service support elements of a MEB:

(1) the joint high-speed vessel (JHSV), in September 2015 reclassified EPF for expeditionary fast transport;

(2) the mobile landing platform (MLP) reclassified as expeditionary transfer dock (ESD); and

(3) the afloat forward staging base (AFSB) is now EBM, for expeditionary base mobile.

The Navy’s USNS Spearhead (EPF-1) program – formerly the Joint High Speed Vessel — is providing innovative capabilities for high-speed intra-theater movement of troops and equipment.

The EFPs are being built by Austal USA, five of which were delivered to the Navy by the end 2015. They are designed to commercial standards specified in the “American Bureau of Shipping High-Speed Naval Craft Guide.”

The naval vessel rules for building and certifying U.S. Navy ships did not apply to any part of the EFP design––nor did Instruction 9070.1A. Although they are fitted with four weapon positions for light machine guns, they have no other active or passive self-defense capabilities.

Another platform that has received increased notice is the USNS Montford Point (ESD-1)-class vessel.

The ESD’s mission is to serve as a transfer point between large auxiliary cargo and ammunition ships and smaller landing craft, a floating base in non-anchorage depths, to deliver people, equipment and cargo when no friendly ports are available.

The Navy’s program of record calls for two ESDs (both Montford Point and John Glenn have been delivered) and two modified ESBs configured as EBM vessels having the same hull/machinery/electrical features as the ESD, but are configured to support MCM and special-forces operations.

A third ESB is in the offing. USNS Lewis B. Puller (ESB-1) delivered in June 2015. General Dynamics/National Steel and Shipbuilding is the ESD/ESB yard.

Some visionaries have conceived distributed-lethality “mini-ARGs” comprising a surface-warfare-configured LCS (or some future lethal, frigate-like small surface combatant), EPF, combat logistics vessel (T-AKE), and an “up-gunned” ESB for low-end but still-in-harms-way missions, including littoral combat ops.

If funded in 2017, the third ESB could serve as the test platform for (if not the first to deploy with) the Navy’s electro-magnetic railgun, while others see the ESD as the baseline for new-design hospital ships, repair/tender vessels, intelligence-collectors, helicopter/tilt-rotor/UAV aviation support ships to replace MSC’s aging aviation support force and other vessels as active naval imaginations might divine.

These are not L-class amphibs, so we’re not doing forcible entry, we’re not doing the Iwo Jima kinds of things with these ships,” Maj. Gen. Simcock told USNI News. “However, there’s a lot of applicability to the warfighting spectrum towards the lower end that we can use these ships for. . . . Now, the piece that I’m looking at right now is, how far can we push that envelope?

How far can we take these ships—again, not L-class warships—how far can we get toward that higher end?

Meaning, if they were second-, third-, fourth-echelon level ships, could we still use them in conjunction with a higher-end operation like forcible entry?”

“And that’s kind of what I’m looking at right now,” he continued, “how far can I push these ships with the capabilities they provide towards the higher end of the spectrum.

Now there’s a line there I think, and I don’t know where that is, but it would be not prudent of me, the risk would be too high to push these things too fast, too close to the high end. I just don’t know where that line is right now.”

But, just don’t call them warships.

The Marine Corps concurs.

“I want to be clear,” Marine Lt. Gen. Ronald Bailey, deputy commandant for Plans, Policies and Operations, underscored in an October 2015 Navy Times interview, “these alternative platforms are not substitutes or replacements for amphibious combat ships.”

The 30 amphibious ships in the Navy’s inventory in early 2016 are, without a doubt, survivable warships in name and reality.

In a May 28, 2014 commentary in The Washington Times, Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) wrote, “Amphibious ships have been called the ‘Swiss Army Knives’ of the sea and America’s ‘911 force.’

They are versatile and responsive, making them one of the most valuable assets of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps.

That is why we turn to them time and again––from major combat missions to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.”

The LHD-1 Wasp class (built by the former Litton Ingalls) comprises eight multi-mission amphibious-assault warships. The ship’s primary role is to provide embarked commanders with command and control capabilities for sea-based maneuver/assault operations employing elements of a landing force comprising helicopters, tilt-rotor aircraft and amphibious vehicles.

Other roles include power projection and sea control, as well as crisis response and combat operations. At survivability Level 2, all are fitted with passive and active self-defense features, including two 20mm Phalanx Close-In Weapon Systems (CIWS), Sea Sparrow surface-to-air missiles and Rolling Airframe Missiles (RAM), and several electronic-warfare (EW) “soft-kill” systems.

The America (LHA-6/-7)-class amphibious assault ships built by Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) are the newest components of the Navy’s expeditionary forces and are also at survivability Level 2 with passive and active self-defense capabilities, including two CIWS, Sea Sparrow missiles and RAM “hard-kill” systems, and several EW “soft-kill” systems.

The eight Whidbey Island (LSD-41) and four Harpers Ferry (LSD-49) dock landing ships carry, launch and recover amphibious assault vehicles, landing craft and operate helicopters and MV-22 aircraft. Built by Avondale Industries and Lockheed Shipbuilding, both classes were designed to survivability Level 2 with passive and active self-defense capabilities including two CIWS and RAM “hard-kill” systems, and several EW systems.

The San Antonio (LPD-17)-class landing platform dock ships being built by HII can launch and recover traditional surface-assault craft as well as two LCACs to transport cargo, personnel, tracked and wheeled vehicles, and tanks. Aviation facilities include a hangar and flight deck to operate and maintain tilt-rotor and rotary-wing aircraft and UAVs.

Designed to survivability Level 2+, because the design includes several selected Level 3 features, LPD-17s are fitted with passive and active self-defense capabilities, including two Mk 46 Mod 1 30mm cannon and RAM “hard-kill” systems, and several EW systems.

The Navy and Marine Corps recognized the need to move out quickly on an 11-ship LX(R) follow-on class to the LPD-17 program to replace the 12 Whidbey Island and Harpers Ferry dock landing ships that are fast approaching end of service life.

In the meantime, to ensure expeditionary-amphibious requirements will continue to be met, numerous observers called for keeping the “hot” LPD-17 line open by building a 12th San Antonio-class warship––it has been approved––as a bridge to the next-generation ’Gator.

The design of the next amphibious warship––whether to start from a clean sheet of paper or use an existing ship for modification to an LX(R) configuration––was resolved on Oct. 14, 2014, when Navy Secretary Ray Mabus approved a ship using the LPD-17 hull form.

“Through a focused and disciplined process that analysed required capabilities and capacities, as well as cost parameters,” Allison Stiller, then-deputy assistant secretary of the Navy (Ships) noted in an email exchange with the author, “the Navy determined that a derivative of the LPD-17 hull form is the preferred alternative to meet the LX(R) operational requirements.

By selectively reducing LPD-17 requirements and de-scoping specific spaces and equipment, we can deliver sufficient capability and capacity to meet the LX(R) mission sets using an LPD-17 derivative design with costs that are well understood.”

The need for LX(R) survivability is well understood, too. According to the Navy’s Team Ships, the LPD-17 variant will be acquired using a revised survivability requirements-generation process.

Rather than working to a specified list of recommended survivability features, the revised instruction requires that the survivability features of a new ship design will be derived using the ship’s concept of operations––where, when, and how the ship will be used in combat––and a specified minimum capability after threat weapon damage.

That allows for an optimized set of threat weapon-based survivability features that accounts for threat attrition as part of the normal preparations for an amphibious assault as well as the protection provided by escorting naval forces.

The Navy’s ’Gators do not come cheap. According to the Government Accountability Office,America (LHA-6) cost about $3.36 billion.

But the nation’s return on the Navy’s investment is full-spectrum, expeditionary presence, power projection and warfighting capabilities in the multi mission, survivable amphibious warship fleet.

And, while some analysts might argue it is better to have less expensive and less survivable ships to help bolster force levels, emphasizing quantity over quality to reach and sustain the 54 amphibious warship force, that calculus ignores important intangible costs––loss of life and mission failure––beyond the tangible cost of the ship, itself.

The EPFs, ESDs and ESBs will fill important “ancillary” niches in benign and low-threat scenarios, including roles and tasks not contemplated when these ships were designed.

“They’ll never replace what I call the Cadillac, they’ll never replace an L-class ship,” Maj. Gen. Simcock said. “But there’s so many ways that we can use them to reinforce the missions we’re doing.”

All good.

However, if the Navy buys lower-cost, low-survivability vessels and puts them into harm’s way without adequate passive and active protection against burgeoning undersea, surface and air/space-borne threats, it runs the unacceptable risk of cheap kills––missions, ships and people.

As the Navy and Marine Corps look to assure their continued ability to project expeditionary military power from the sea, it would be good to remember the (so-called) Invincible.

This piece first appeared on USNI News and is republished with the permission of the author.

http://news.usni.org/2016/02/04/essay-when-in-comes-to-ship-survivability-prayer-isnt-enough