If ever one wanted proof that disruption of advanced networks is a challenge and a problem, look no further than the recent disruptions of air traffic in the UK and beyond from a reported drone sighting near the airport and the follow on events.

Just today, the UK MoD has withdrawn the military systems they had deployed to deal with the threat and to date, no one has been held accountable for the incident.

According to a BBC News story January 3, 2019:

A £50,000 reward for information has been issued by Crimestoppers, which said it had “passed on close to 30 pieces of information to law enforcement within the first 24 hours”.

A suggestion by a senior Sussex police officer that there may have been no drones was later dismissed as a “miscommunication”.

The force said it was investigating “relevant sightings” from 115 witnesses – 93 of whom it described as “credible” – including airport staff, police officers and a pilot.

Chief Constable Giles York had said some of the drones spotted may have belonged to the police and caused confusion.

However, he said he was “absolutely certain” that there was a drone flying near the runway during the disruption.

The MoD said: “The military capability has now been withdrawn from Gatwick. The armed forces stand ever-ready to assist should a request for support be received.”

And this new entry in Wikipedia provided a short characterization of the incident.

Between 19 and 21 December 2018, hundreds of flights were cancelled at Gatwick Airport near London, England, following 67 reports of drone sightings close to the runway. The incident caused major travel disruption, affecting about 140,000 passengers and over 1,000 flights. It was the biggest disruption since ash from an Icelandic volcano shut the airport in 2010. On 21 December, Sussex Police arrested two suspects, who were released without charge on 23 December.

The persistent drone crisis at Gatwick, located 45km south of London and which serves 43 million passengers a year, has had ripple effects throughout the international air travel system.

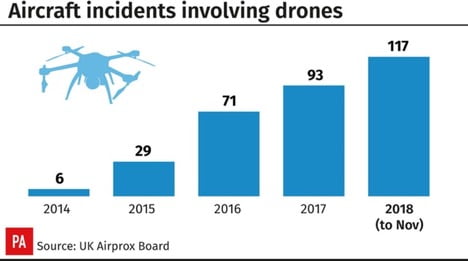

The Gatwick drone disruption is clearly not the only one as the chart above highlights. And the problem is a ongoing challenge facing airports as well as other technologies such as laser technologies.

A press release from Drone Shield, an Australia company also based in the US provided a comment on the incident and highlighted the challenge.

Several important lessons can be drawn from the events at Gatwick.

- Drone misuse is a universal problem. There is virtually no government in the world that does not require protection against drones, as do large numbers of commercial users (such as stadiums, event venues, power plants, airports and others).

- Inaction is not an option. The costs of inaction are huge, and drone attacks will continue to proliferate, grow in sophistication, and intensify.

- Many purported drone mitigation products are concepts in development and have not been deployed at all or have only been tested in a narrow range of situations or controlled environments.

- Cost is not a predictor of performance. The media has reported that systems that could cost up to £20 million (US$26 million) were brought in to deal with the rogue drones. Nevertheless, the drones were not defeated for approximately 48 hours.

- The cost of many drone mitigation systems renders it prohibitive for most “soft” targets to use these expensive systems on a day to day basis.

An article in Drone Life added its assessment:

A serious wake-up call

The first is that airports around the world need to be proactive and put stronger measures in place to prevent this kind of disruption from happening. The ease with which an individual or small group was able to bring Gatwick to a standstill is frightening. There’s no reason to believe this weakness won’t be exposed again.

It appears as though the British military eventually brought in an Israeli counter drone system from defence electronics company Rafael Advanced Defense Systems. The company’s ‘Drone Dome’ solution (above) is made up of a radar-based system that identifies targets, a laser system that neutralizes the drone, and a jamming system that disrupts communications between the drone and its operator.

The fact that this technology was not already in place suggests a worrying level of complacency when it comes to protecting UK infrastructure. Particularly given the rising number of near-misses reported around UK airports and incidents involving drones delivering contraband to prisons. Alternatively, it’s exposed the systems that were in place as completely ineffective.

Fortunately, the individuals involved seemed intent on causing disruption rather than something more sinister. Just imagine what could happen if a sophisticated team, armed with multiple weaponized drones and the ability to avoid current countermeasures set their sights on an airport or public event in the future.

With that in mind, it’s worth considering that we were lucky this time. We don’t know whether it was technical limitations or alternative motives that prevented this incident from becoming deadly, but the potential is there and has been for a while. This should be a wake-up call.

Sadly, there doesn’t appear to be a silver bullet counter-drone system out there capable of dealing with every type of threat. Every method has strengths and weaknesses and most can be circumvented by a determined, sophisticated group that knows what it’s doing.

The winning counter-drone companies will be those that quickly move beyond basic detection and mitigation and start thinking about scarier, more advanced scenarios in which the next generation of computer vision and autonomy is combined with deadly payloads and malicious intent.

It seems a matter of time. Will we be ready?

In an article by Chris Stokel-Walker published on December 21, 2018 in Wired provided reactions to the problem.

A spokesperson for NATS, the organisation that oversees the UK’s airspace, says it has been working closely with airports and airlines to mitigate the disruption.

“Flying any kind of drone near an airport or in controlled airspace without the proper permissions is dangerous and unacceptable,” the NATS spokesperson added. “People using drones should apply common sense when deciding where to fly and need to remember that the same legal obligations apply to them as well as any other pilot.”

NATS has worked closely with industry bodies, such as the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), which governs the airspace above the country, and the government “to create an environment that ensures the safety of all airspace users while supporting the growing use of drones,” they said.

“There’s a constant problem and the CAA have known about this for years,” explains Andrew Heaton, an independent drone expert. “It’s about trying to make people aware there are laws and regulations in place.”

While the pilots of the drones have still not been found, what they’re doing is illegal. On social media, police have requested anyone with knowledge of who may be behind the incident to come forward.

“At the end of July this year the CAA revised the air navigation order to make it explicit that you can’t fly a drone within a kilometre of an airport, regardless of where you take off from,” explains Owen McAree, a drone expert at Liverpool John Moores University.

Finally, a column by Max Hastings in the Times highlighted a broader assessment of what the Gatwick incident forebodes.

Our military have until now downplayed the risk of terrorist drone strikes in Britain. Commercial UAVs such as those which carried out the Gatwick attack — and an attack is what it surely was, in effect if not in intent — can carry relatively small payloads, and thus charges.

As one expert says: “You do better to steal a car and pack it with explosives.” Yet the Isis attacks in Iraq described at the beginning of this article highlight a different threat: the use of commercial or even hobby surveillance drones to pinpoint targets for other weapons systems, whether ground-fired rockets or missiles.

We can and should provide drone protection for airports and government installations. But the difficulties are almost insurmountable of defending every vulnerable target in Britain against drone-guided terrorism.

I have believed for years that we have been rashly complacent, viewing drones merely as a convenient western tool for watching and when necessary killing our enemies in far distant places. UAVs will play a key role in future conflicts, terror and anti-terror campaigns, and this will assuredly not always be one to our taste or advantage.

The Gatwick shambles is a foretaste of the disruption, and probably eventually deaths, that UAVs in the hands of our enemies can inflict upon a peaceful, relatively vulnerable society such as our own.

For the full article, see the following:

The featured photo was taken from the Wired article cited above.