By Robbin Laird

On February 7, 2020, the US Navy officially received its first CMV-22B Osprey, the replacement for its venerable C-2 Greyhound aircraft.

I attended the ceremony held at Amarillo, Texas and had a chance to talk with a number of the participants before and after the ceremony.

Having followed the Osprey since 2007 and observed its impact on the USMC, it was never a simple case of the MV-22 replacing the CH-46 ‘Phrog’ and its mission.

The tiltrotor is not the same in any real sense as a traditional rotorcraft, and the increased range and speed of the Osprey and its unique operating envelope has proven to be a significant capability for the Marine Corps which they have been able to leverage to transform their core operations.

Now the US Navy will be transitioning from a fixed-wing aircraft configured to operate with the cats and traps system onboard an aircraft carrier (the C-2) to an aircraft (the Osprey), which is not limited by that system will not operate in any way like a C-2.

It is undoubtedly going to also be a significant opportunity for the Navy to manage the transition and to understand fully how to make the most of the new aircraft’s capabilities to conduct Airborne Logistics from the Sea Base in new and innovative ways.

There is another major aspect or indeed opportunity, that has nothing to do with the COD (Carrier On-board Delivery) mission.

The Osprey has proven capable of a wide range of operations, from Special Forces transport to performing a Medical Evacuation off of a submarine, but the US Navy is not buying it for those missions.

Yet, given the demanding strategic environment in which the fleet is operating and going to operate, it is difficult to believe that the Navy will not wish broaden the envelope of what the Osprey can do for the fleet.

To do so will lead inevitably to the demand to buy more than a simple COD replacement would dictate.

Because the Osprey is a multi-service, and multi-national asset, there will be opportunities as well to leverage collaborative investment as well.

This has not been possible with the C-2 because it was and is a uniquely Navy plane.

How then might the Navy use the aircraft beyond the classic C-2 ops rhythm?

And how might the Navy take advantage of a broader investment or production set of opportunities posed by multi-service and multinational partners?

What is clear is that the challenging path of transition which the Marine Corps took from CH-46 to MV-22 will not be as difficult for the Navy.

They can already build on the experience of the Marine Corps.

Nonetheless, it is clear that there will be unique aspects of its fleet introduction.

During my visit to Amarillo in February 2020, I had a chance to talk with a retired Navy officer who was involved throughout his career with the C-2 as well as becoming involved in the process of working the C-2 replacement effort.

Currently, CAPT (ret.) Sean McDermott is a commercial airline pilot who served in the US Navy for 26 years. He was involved with the C-2 during the majority of his career, starting as a Greyhound pilot and eventually commanding one of the Navy’s two fleet logistics squadrons.

In the final years of his service, McDermott was involved in working through options for the Navy as they considered C-2 replacements, with an eventual Osprey selection.

In our discussion, McDermott highlighted a key point which logistics pilots are keen to underscore: “You don’t care about logistics until you don’t have the supplies you need at the time you want them.”

He noted that when he became part of the C-2 community, there were two squadrons, based at three locations.

One, VRC-40 ‘Rawhides’ was located on the East Coast at Norfolk, VA, and the second, VRC-30, ‘Providers’, on the West Coast in San Diego California. There is also a permanently forward-deployed detachment of VRC-30 based in Iwakuni Japan.

Both squadrons fall under Airborne Command & Control and Logistics Wing (ACCLW) headquartered in Point Mugu, CA. The wing was traditionally led by officers with an E-2 Hawkeye background.

This meant that there was little opportunity for C-2 pilots to lead the community beyond the possibility of becoming a squadron commander or O-5 (Commander) rank, vice O-6 (Captain/Commodore) rank.

Lacking the upward mobility, post-squadron command has made it more difficult for the C-2 leadership to become involved in future planning and to be able to be in the best position their assets for more robust mission opportunities.

As a story published in 2010 in the Virginian Pilot newspaper noted for the 50th anniversary of VRC-40:

McDermott and the other members of his squadron, known as the Rawhides, aren’t used to being the center of attention. In naval aviation, glory usually goes to the fighter pilots and their jets, not to those who deliver mail, spare parts and passengers.

“We’re a light switch. We’re the Internet.

They expect us to be there all the time,” McDermott said.

“The only time we’re visible is when we’re not there.”

McDermott underscored the challenges facing C-2 leaders getting into a position to shape the future of their mission within the overall world of carrier aviation.

“In general, there is no upward mobility for C-2 COs.

“In general, the preponderance of the leadership of the wing are E-2 Naval Flight Officers.

“This means that you’ve got somebody who’s your boss who’s never flown your plane, never done your mission, doesn’t have a complete understanding of the challenges that are unique to deploying detachments across the planet.

“They had about 140 people in their squadron when they were commanding officers and a C-2 squadron is 400 people.”

McDermott noted that one of the encouraging signs with the CMV-22B transition is that a new Wing, COMVRMWING has been stood up, and its Commodore who is in charge of the Osprey team now being charged to take over the COD mission.

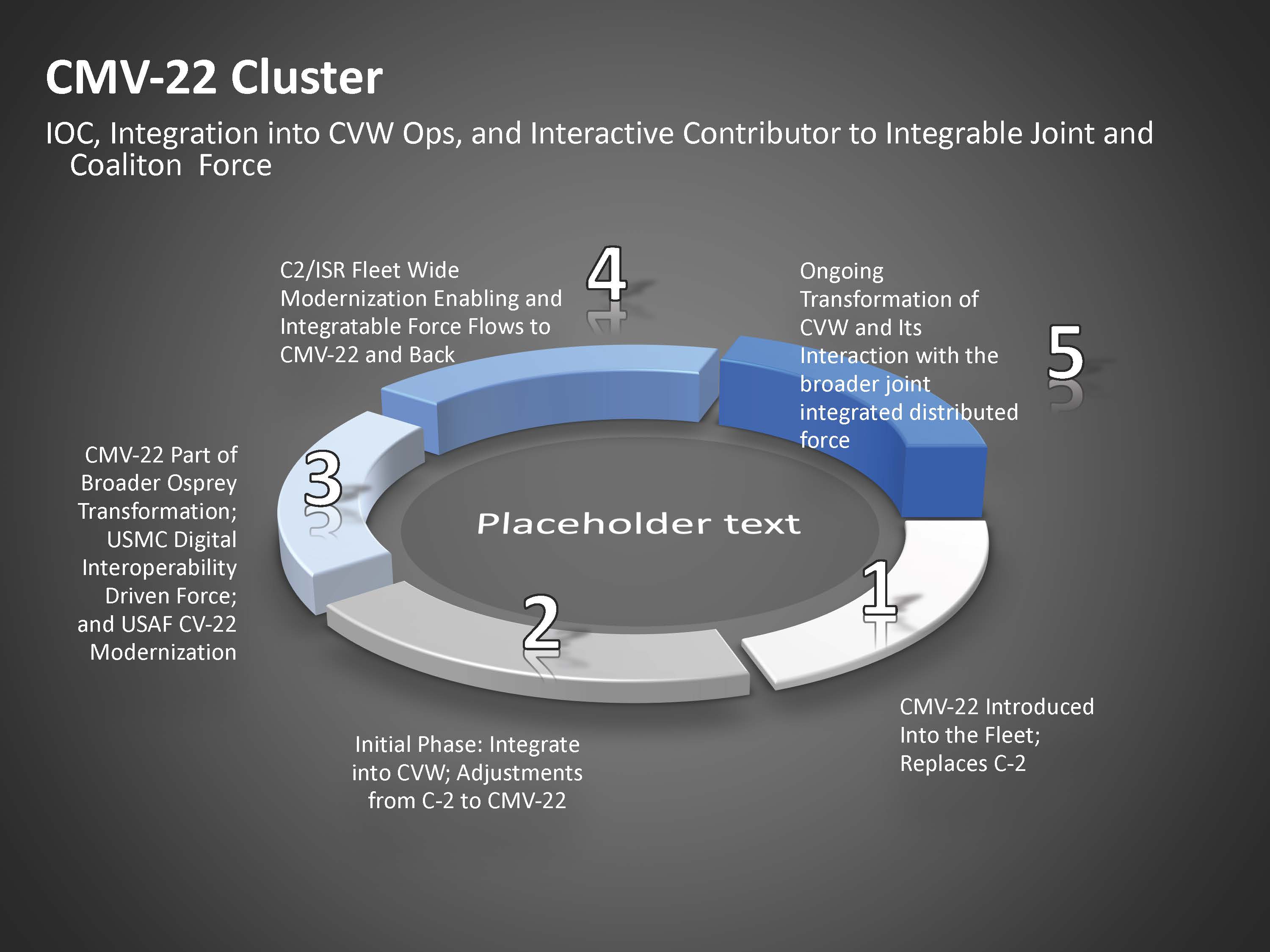

This CMV-22 wing should provide a more dedicated voice to implement new ideas for airborne logistics operations as well as exploring how the aircraft could be used to support other missions for the Navy in a distributed maritime environment.

We discussed at length his experience with the challenges of getting the Osprey engaged with the Navy fleet and eventually on to the carrier for a fleet battle experiment as well as in support of humanitarian assistance missions.

He was also involved in the efforts to deploy Ospreys onto foreign ships, and he worked closely with the Marine experimental squadron VMX-22 and Col. Michael Orr, who we interviewed often during the time frame when the Osprey transition was accelerating, to leverage the Marine’s experience with the aircraft to shepherd Navy interest.

On the cover of our book, Rebuilding American Military Power In The Pacific, we chose a photo of Col. Orr landing on the USS George H.W. Bush.

McDermott was on that carrier during those trials and highlighted how challenging it was to get support to land the Ospreys onboard the large deck carriers.

The Marine aviation leadership created VMX-22 to lead the way forward, first with Ospreys and preparing the way for the next round of aviation innovation.

Because they worked under strong leadership, they could partner with a Navy leader like McDermott to create an opportunity for the Osprey to become a large deck carrier asset.

As McDermott noted about Col. Orr: “I have a lot of respect for Mike, clearly a leader who is willing to support change and innovation.”

But as the trials evolved, there were opportunities to demonstrate how an Osprey could do things a C-2 never could do, given the flexibility of the aircraft and its speed and range.

He provided several examples of this.

One involved when Orr’s group arrived back in Norfolk on an Osprey, and when taxying, out came a chief petty officer blocking their way. They stopped and the chief said that there was an urgent need to get a part to an F/A-18 Hornet so that it can fly off of the carrier prior to getting to port.

The ship was pulling in the next day, and if they did not get the aircraft off of the ship, the aircraft would need to be craned off the ship while in port, not something the Navy likes to do.

The catapults have already been shut down on the ship and were not available.

Obviously, this was not a barrier for the Osprey which flew to the ship, delivered the part and left within 90 seconds from the ship.

McDermott recalled: “The Air Boss on the carrier was an E-2 guy and he underscored, “Let’s see a COD do that!”

We concluded our discussion by focusing upon the potential impact of the multi-mission Osprey to the fleet.

McDermott put it this way: “With the C-2 we did one thing – Carrier On-board Delivery.

“With the Osprey, Combatant Commanders already know the multi-mission capability of the V-22 and will be tempted to utilize them for a variety of other missions.

“This is not something that would happen with a C-2. Carrier leadership will eventually struggle to fence off their logistics assets from outside tasking.”

In other words, there is an anticipated operational demand that they will want to leverage fully the new versatile capabilities of the Osprey.

He noted that with the new platform being introduced to carrier aviation, it will be possible to leverage it to shape a greater range of capabilities for the COD asset.

He noted that as the Marines began to get comfortable with the MV-22, they shaped the unique Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force (SP-MAGTF), which has become a highly demanded asset.

He argued that such innovation was certainly possible for the Navy as it worked with its new COD aircraft.

One area he noted were forward deployed locations that would benefit like operations in Bahrain.

Ospreys deployed to these locations could not only better support logistics but would also have the flexibility to support other mission sets for combatant commanders.

“With the coming of the new platform into the fleet, one innovation which might be considered is how to use the new Navy Osprey as part of a broader sustainment effort encompassing Marine Corps and Navy Ospreys.

“It also is an area where the multi-mission capabilities of the aircraft for the Navy can be explored as well.

“In other words, where the Marines leveraged their Ospreys to build and equip SP-MAGTF, perhaps the US Navy can leverage the Bahrain anchor from which to build regional sustainment and explore ways to build out the multi-mission capabilities it would want from its CMV-22s.”

This clearly might require the Navy to consider from the outset ways to ramp up the buy and to prepare for ways in which the fleet commanders will employ it to leverage fullythe aircraft capabilities, and, at the very least, utilizing its capability to provide improved logistics to Navy and Maritime Sealift Command ships.

But that is a subject for another article.

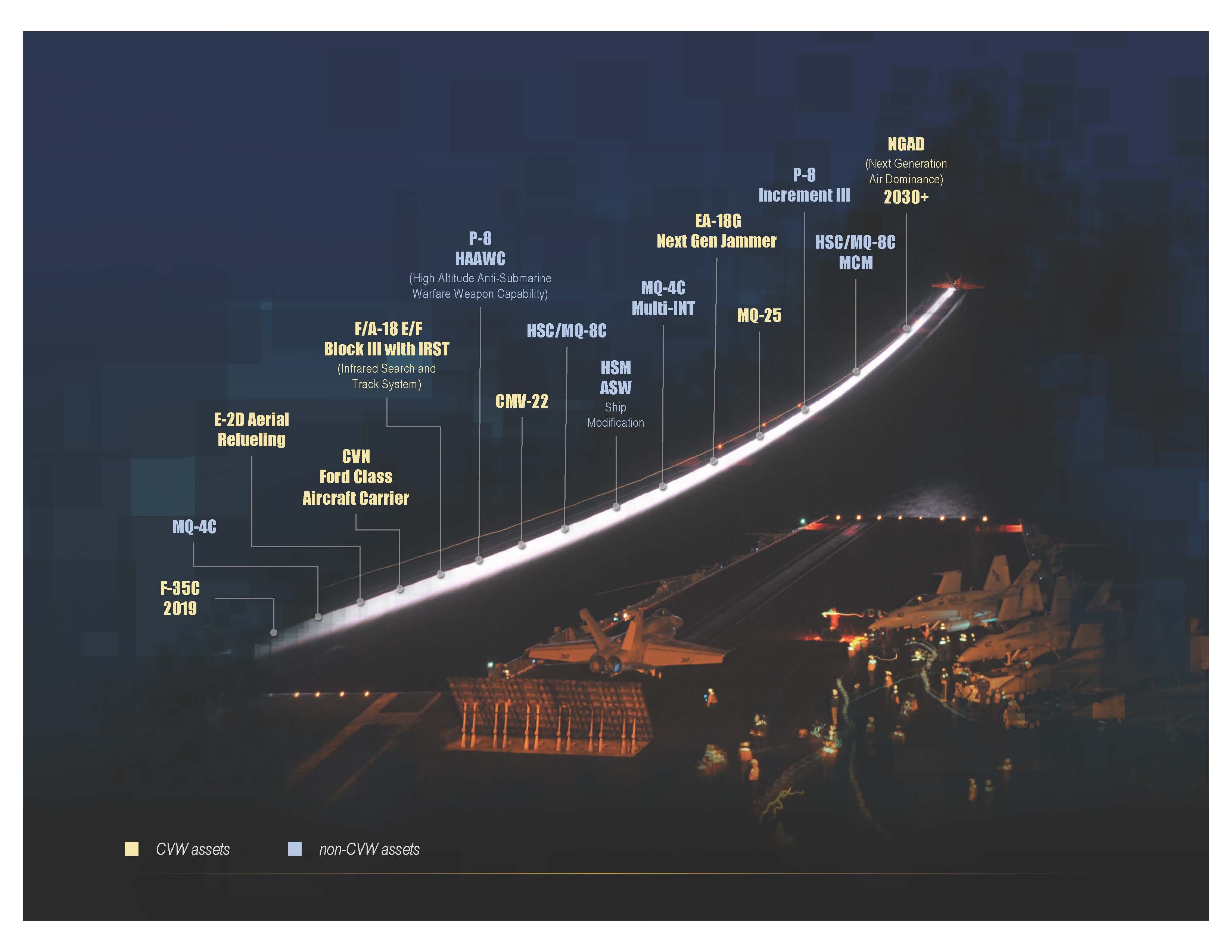

Carrier Air Wing innovations highlighting platforms coming onboard which will shape clusters of innovations driving forward innovation onboard the large deck carrier. Credit: US Navy

Featured Photo: ATLANTIC OCEAN (Aug. 9, 2018) Two MV-22 Ospreys, attached to Air Test and Evaluation Squadron (HX) 21, fly over the aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77). The ship is underway conducting routine training exercises to maintain carrier readiness. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Brooke Macchietto).

Also, see the following:

Shaping a New Capability for the Osprey: Delivering the F-35 Engine to the USS Wasp